Crab Butter Rice

Crab Butter Rice is unlike any other crab dishes: it is a seasonal delicacy that exclusively combines the autumn crab's paste and roe without using any of its meat. Cultural historian Cheng Pei-kai shares his experience eating it, and its peculiar and debatable origins from Suzhou brothels.

When a friend of mine was travelling in Japan recently, he chanced upon the Japanese version of the TV programme "A Bite of China". It happened to be the episode in which I appeared, savouring exquisite dishes from a literati feast in Suzhou. As he was salivating over the images on screen, he snapped a picture and sent it to me, asking me what other extravagant dishes I tried, apart from the intricately cooked striped bass and steamed goose that were featured. I replied that the documentary had not included the crab butter rice.

This unique choice of ingredients takes crab-eating to a transcendental level.

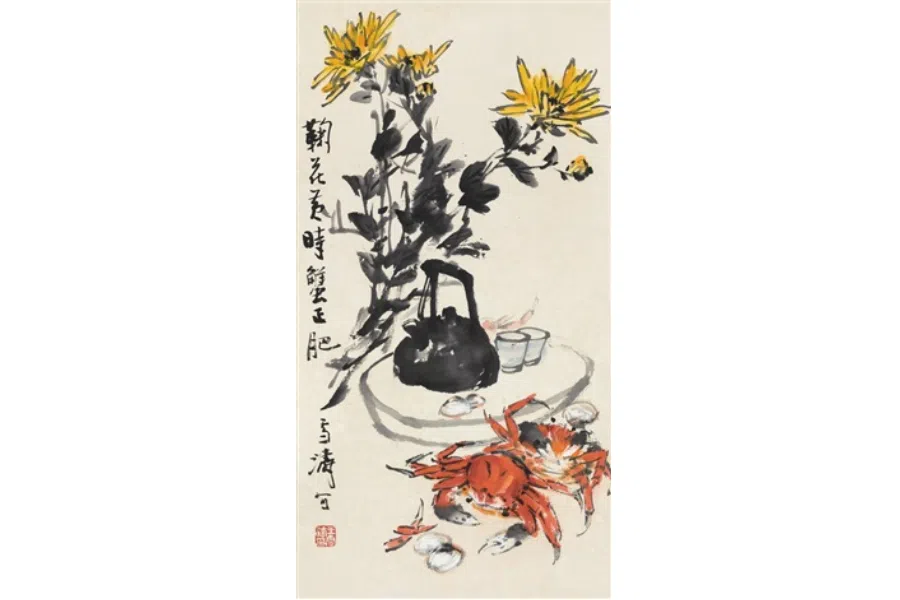

This crab butter rice is not just any regular butter rice. It is a much more sublime version, a concoction of crab paste and crab roe mixed into rice. According to Suzhou residents, the reason it is called "crab butter" (秃黄油, tuhuangyou) is that the Chinese word 秃 (tu) sounds very similar to 忒 (tei) in the Wu dialect, meaning "only" or "exclusive". As a seasonal delicacy, the autumn crab's paste and roe are combined, without using its meat, to create "crab butter", unlike the usual local dishes that mix in the meat. This unique choice of ingredients takes crab-eating to a transcendental level.

Autumn is when hairy crabs spawn and start filling with roe. It is the seasonal crab roe and paste that is specially extracted to make crab butter. Onion and ginger are first stir-fried in goose fat or lard before the female crab's roe and the male crab's paste are added. This mixture is then simmered with huangjiu and seasoned with broth. The mix is then drizzled over a bowl of rice and mixed well, resulting in a bowl of fragrant, savoury goodness. Nothing comes close to this exquisite taste. In some renditions of the dish, perilla is added to reduce "fishiness", along with a sprinkle of sugar catering to the preference for sweet flavours in Suzhou cuisine.

The process for making crab butter involves extremely tedious, painstaking work, demanding close attention to the smallest of details. It's no wonder the dish comes with a big price tag. Two years ago, an old Suzhou restaurant brought crab butter noodles back to its menu, selling the delicacy for 200 RMB per bowl. Although this was ten times more expensive than the already lavish signature pork belly noodles, the rare dish was worth every penny. From the Ming and Qing dynasties until the Republican Era, crab butter remained the star dish for nobles and elites, available only to the upper classes who had private chefs at their beck and call. The amount of effort that went into every bowl of crab butter was so unimaginable that, the idea of sampling it wouldn't even cross a commoner's mind.

People say crab butter originated from brothels, a gimmick used by skilful prostitutes to "lock" their clients' stomachs and trap them for eternity. This is possible, but cannot be taken as a certainty, so it is unfair to say, "If not for the brothels, the world would not know crab butter." The people of Suzhou were refined, and their refined taste was not limited to prostitutes.

A read of Six Records of a Floating Life (《浮生六记》) introduces the reader to the story of Yun Niang, just the kind of virtuous, thoughtful wife who was likely to prepare a bowl of crab butter rice for her husband each autumn. The need to emphasise the brothel's defining influence on the culinary world and the idea that the brothels were what validated mankind's longing for food and lust is simply preposterous. Feasting then immediately thinking about a lady of the night, or eating crab butter rice and thinking about its "creamy, savoury goodness perfectly coating each grain of rice, creating an elegant party in the mouth" (comment by a gastronome) are but the narrow ideas of the lascivious mind.

Suzhou cuisine is closely related to its traditional entertainment scene. It was customary in ancient times to have singers and dancers accompany extravagant feasts. Being in close proximity to Lake Tai, Suzhou was known for its freshwater delicacies and grains and was home to famous floating restaurants (画舫船菜). These restaurants were situated amidst an environment of luscious greens and vibrant reds, stretching from outside Changmen to Tiger Hill's nearby Shantang Street. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, these restaurants provided scholar-officials with the perfect place for feasts, poetry, and wine.

Whether they were at Qinhuai River or Shantang Street, they were simply trying to enjoy life with a glass of wine in hand, beautiful women by their side, and fine delicacies in their stomachs.

As illustrated in Records of Wumen's Floating Boats (《吴门画舫录》), written in the Qing dynasty during the Jiaqing reign, "The southeastern metropolis of Wumen (Suzhou) is a bustling city, unrefined but gorgeous. For a fine feast, row to Tiger Hill (Hu Qiu), where music floats among wooden boats throughout the four seasons. Wander through swaying willows, quaint alleys, and hidden pavilions. Stay and drink to your heart's content in the silver lights and golden vessels. Recall Zhao and Li, their beauty, their arts, and their stories. Be saddened by their drifting lives, and reflect on their displacement." (吴门为东南一大都会,俗尚豪华,宾游络绎。宴客者多买棹虎丘,画舫笙歌,四时不绝。垂杨曲巷,绮阁深藏。银烛留髡,金觞劝客,遂得经过赵李,省识东风,或赏其色艺,或记彼新闻,或伤翠黛之漂沦,或作浪游之冰鉴。)

The mention of "Zhao and Li" here refers to Yu Huai's Banqiao Travelogues - Extravagance (《板桥杂记 · 雅游》). It reads, "Riding handsome horses are royalty and the elite classes, leading extravagant lives and travelling by the lakes and seas. Bows under their arms and flutes to their mouths, they enjoy their outing as if accompanied by Zhao and Li, and each feast is accompanied by music." (宗室王孙,翩翩裘马,以及乌衣子弟,湖海宾游,靡不挟弹吹箫,经过赵李。每开筵宴,则传呼乐籍。) Today's young people have no idea who Zhao and Li were. Of course they don't know, since their harebrained (and often lustful) thoughts are so different from the people of ancient times, and their manner of inviting "prostitutes" to the dining table is also vastly dissimilar. They wouldn't associate "Zhao and Li" to "Zhao Feiyan" (end note 1) and "Lady Li" (end note 2), both of whom attempted to charm Han emperors with their outstanding beauty.

The literati's indulgence in life's guilty pleasures was not unreasonable. The literati of the Ming and Qing dynasties often grew bored. Whether they were at Qinhuai River or Shantang Street, they were simply trying to enjoy life with a glass of wine in hand, beautiful women by their side, and fine delicacies in their stomachs.

Are fine delicacies of floating restaurants related to crab butter? They are. In an ancient menu (Wang Si's Floating Restaurant Menu 王四寿船菜单) that records the delicacies served in floating restaurants, one of the 30 main dishes, Golden Opulence (遍地黄金), was crab roe.

End note

Zhao Feiyan (赵飞燕)

Zhao Feiyan (赵飞燕)

Zhao Feiyan was Empress Xiaocheng (孝成皇后) to Emperor Cheng of the Han dynasty (汉成帝). Zhao Feiyan and her sister Zhao Hede (赵合德) were greatly favored imperial consorts who stole the Emperor's affection from Empress Xu and Consort Ban. After falsely accusing Empress Xu and Consort Ban of witchcraft, they dominated the palace. Eventually, Zhao Feiyan became Empress and the Zhao sisters allegedly resorted to numerous dirty tricks to prevent other concubines from bearing the Emperor any children.

Lady Li (李夫人)

Lady Li (李夫人)

Lady Li, a concubine of Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty (汉武帝), was later named Empress Hanxiaowu (汉孝武皇后). She gained favour and love from the Emperor due to her beautiful appearance.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)