Interference in China's media industry: Even Global Times editor Hu Xijin 'cannot stand it'

China celebrates Journalists' Day on 8 November every year. While Chinese media practitioners posted their reflections on social media, Global Times editor Hu Xijin laments increasing interference from government departments and local governments in media work. As the function of Chinese media as a mouthpiece is strongly emphasised, would Journalists' Day have to be called "Mouthpiece Day" instead?

Before I became Zaobao's Beijing correspondent, I did not know that there was a day specially dedicated in honour of people working in the news industry in China. This is called Journalists' Day, and it falls on 8 November. This year also marks the 22nd Journalists' Day in China.

This day each year, I would receive wishes from Chinese friends who often worked with the media industry, and also see Chinese colleagues or former journalists post various kinds of reflections on social media, some of which are related to the huge changes that the media industry has experienced, while others are mainly about what led them to become a reporter, or their personal journalistic ideals.

On Journalists' Day this year, I saw a few colleagues paying tribute to Southern Weekly founder Zuo Fang, who passed away earlier this month, on their WeChat Moments.

Southern Weekly, known for being bold to speak up, once left a deep imprint on Chinese journalism history and can be said to have influenced a generation of Chinese public intellectuals. Following news of Zuo's death, a former journalist who worked at Southern Weekly recalled Zuo's journalistic ideals and the days of seeking truth back then, lamenting the changing times following the 2013 "Southern Weekly incident" involving the authorities rewriting the paper's pro-reform New Year's Day editorial.

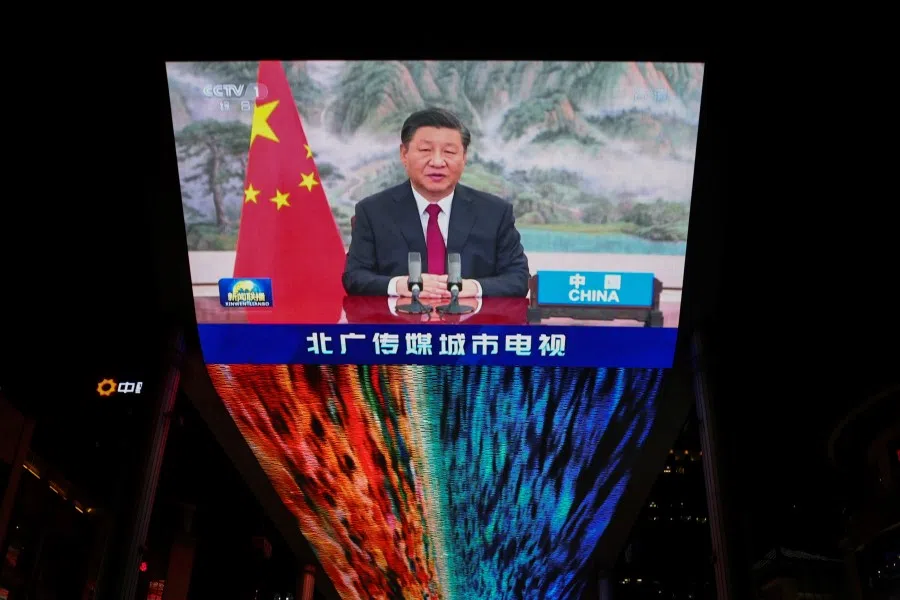

Also on Journalists' Day itself, state media Global Times editor Hu Xijin posted a 1,600 word essay on Weibo, saying that it is "becoming more and more difficult to do media". He also admitted that "media practitioners have been subject to increasing restrictions for some time".

Hu said that government departments and local governments, as well as various influential institutions, "require the media to closely cooperate with their work and constantly ask what the media should and should not report". In particular, when they encounter negative public opinion, they "hope the media can keep silent and help cool the situation".

He claimed that "such specific requirements are on the rise" and has formed "an increasing force of intervention in the work of the media".

Hu thinks that this trend is "very debatable" and that the "publicity front should be accountable to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and to the overall interests of the country". While national interests are often reflected in the work of specific departments and localities, "they are not the same after all".

Hu said that if the media "indulges in serving localities and departments", the media's function as news outlets would be affected and it would lose credibility and combat effectiveness. And the actual result of this would be the "loss of the country's systemic functions". With increasing interference, the pressure of "making mistakes" would be greater, and the enthusiasm of media practitioners would in turn be dampened. Some journalists would also become "more conservative" and "only seek their own safety" as they become influenced by the mentality of certain departments and localities to avoid trouble.

...the vocal Hu has always been thought to be "pro-left", and the Global Times that he heads has also been seen as a leftist bastion within state media. No wonder some Chinese industry colleagues privately lament: "Even Hu cannot stand it."

Hu also tried to make an appeal for the media, saying that when government departments or local governments made an improper statement or decision, the media would often be blamed for reporting it, or so-called creating a "media hype". In cases like this, Hu thinks that "it is the source of the error, not the media, which should be held responsible".

As for the various restrictions on those in the Chinese media industry, it has been heard of in regular interactions with industry colleagues, and it is no secret within the industry. But in comparison to rueful comments by news industry workers used to a free media, it is somewhat surprising for Hu to openly criticise the authorities for interfering with public opinion. After all, the vocal Hu has always been thought to be "pro-left", and the Global Times that he heads has also been seen as a leftist bastion within state media. No wonder some Chinese industry colleagues privately lament: "Even Hu cannot stand it."

The role played by China's media environment and media is very different from that in the West. In the West, the media is called the "fourth estate", an independent force apart from the government's legislative, executive, and judicial branches. It monitors and regulates, based on the premise of a free space for public opinion. While Western media is not totally free of political influence, for example, a lot of media have political leanings even when there is rotation of political power. However, one fundamental principle that Western media holds to is to keep questioning the government.

In contrast, the main role of the media in China is to engage in publicity for the ruling party and government, and not to check authority. The function of Chinese media as a mouthpiece is strongly emphasised, where the authorities require state media to figuratively "be married to the party" and those in the media to be politically correct, to "automatically" toe the official line in thought and deed, and not to question the authorities.

If the media can only engage in publicity and lose the independence that it ought to have, would Journalists' Day have to be called "Mouthpiece Day" instead?

Apart from internal publicity, when it comes to external publicity, over the past couple of years the Chinese media has also been "telling the China story" and projecting Chinese influence. Such a role and position has also led to some Chinese media being tagged as "infiltrators" overseas. From the time of former US president Donald Trump, quite a few Chinese media have been identified as overseas agents of the Chinese government. This is partly due to geopolitical factors stemming from big power competition, but it also has to do with the unique position of the Chinese media.

The political systems and sociocultural environments in China and the West are different, and it is inevitable that they hold different ideas of disseminating news. The media in China cannot be the same as in the West; China also needs its own form of media. However, this does not mean that there is no need for a comparatively open media environment to ensure the smooth flow of accurate information, to safeguard the people's right to know.

Besides serving national interests, the media also works for the good of the country and people, preventing the will of officials and administrative agencies from encroaching on the interests of the people, and ensuring that people have the right to pursue the truth and the facts. If the media can only engage in publicity and lose the independence that it ought to have, would Journalists' Day have to be called "Mouthpiece Day" instead?

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)