Sun Yat-sen and the Xinhai Revolution: A pictorial journey

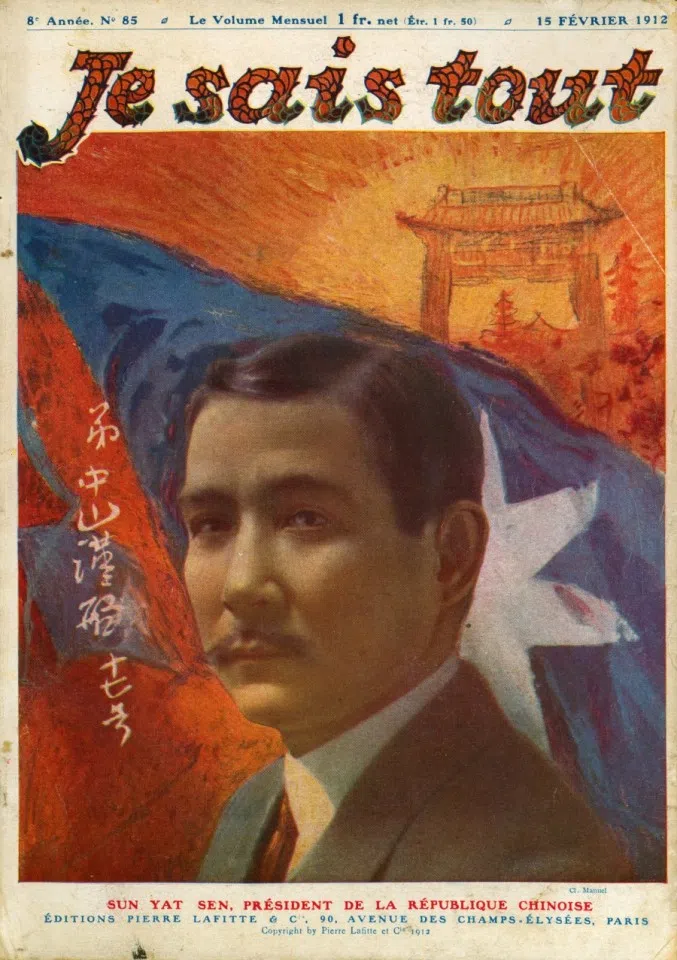

Between October and December 1911, fierce fighting broke out between the revolutionaries and the Qing troops. And by early 1912, China's 2,000 years of imperial rule was history. The Xinhai Revolution led by Sun Yat-sen had successfully united the Chinese people against the imperial system, and built the first Republic in Asia, changing the fate of China and East Asia. Hsu Chung-mao takes us on a visual journey through that period of chaos and upheaval.

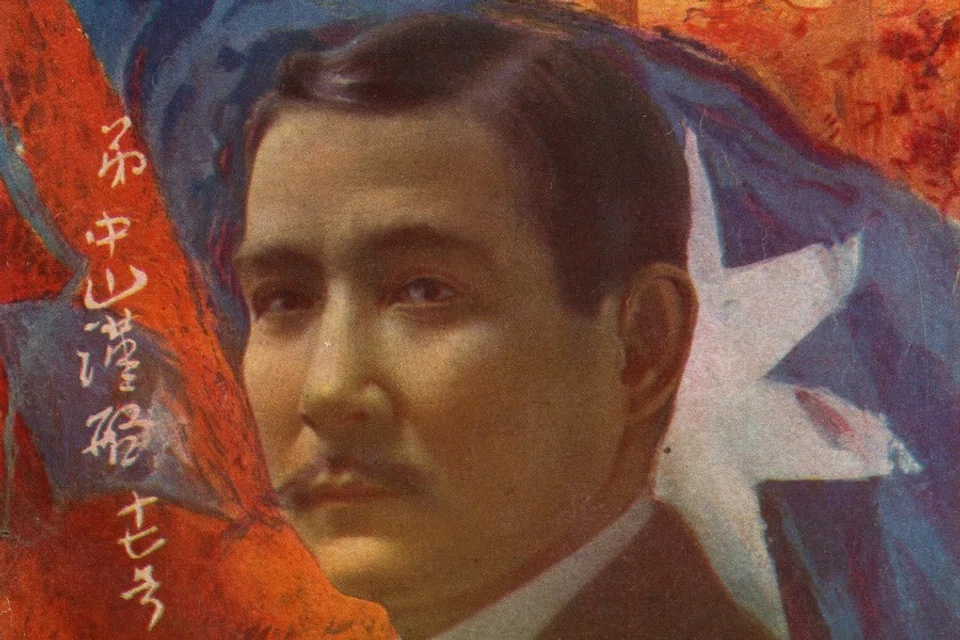

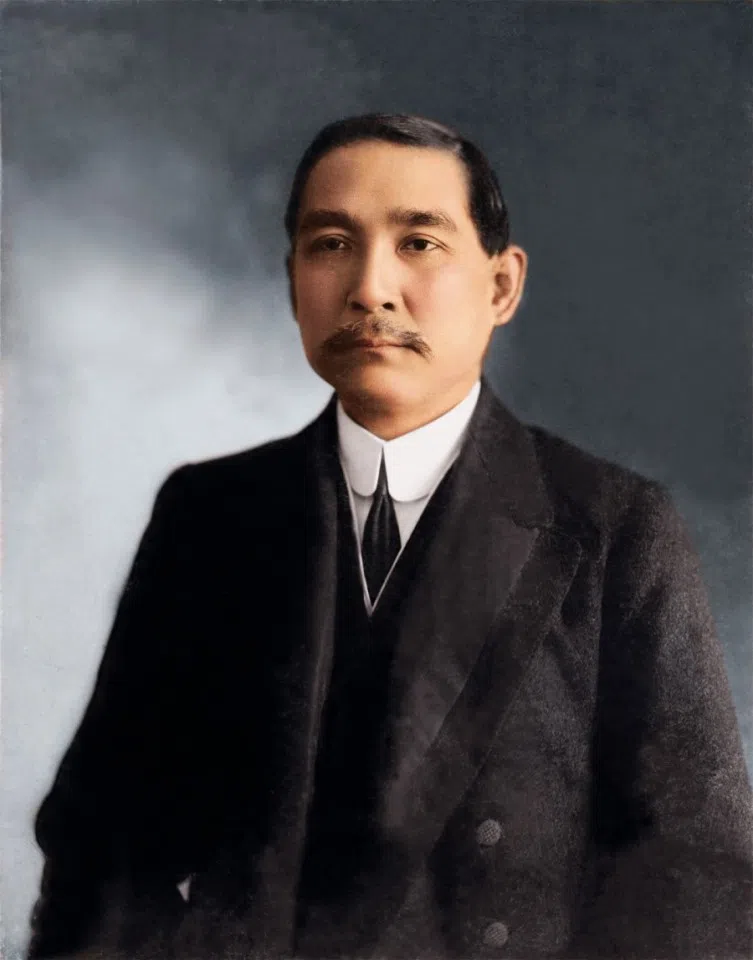

At the beginning of the 20th century, Sun Yat-sen, a revolutionary leader from Guangdong, left his mark on the course of China's destiny. Under him, the Republican revolution overthrew China's imperial system that had lasted thousands of years, and Asia's very first Republic was established, changing the fate of China and East Asia.

Beginning from the first Opium War in 1842 during the late Qing dynasty, China was invaded and colonised by various Western powers; after the second Opium War of 1860, China went on a modernisation drive, but lost the first Sino-Japanese War of 1895 to a similarly modernising Japan. This shook China's confidence as an ancient power going back thousands of years.

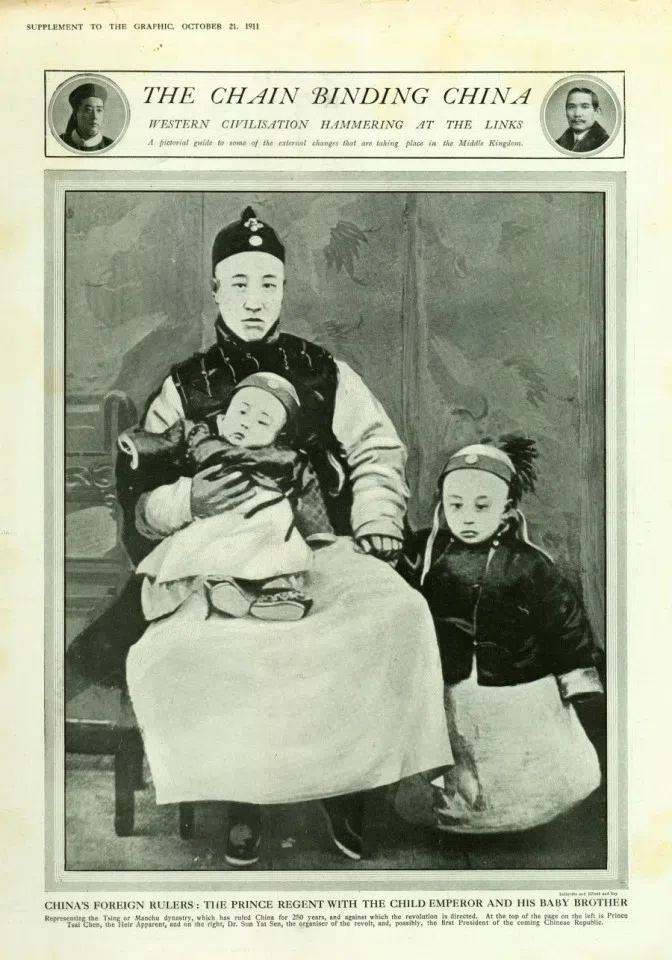

In the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 and the Sino-Russian war of 1905, China's very survival was threatened. The Qing government tried to salvage the situation through legislation, but the situation was fraught and morale was low, and the Qing administration was on the brink of dissolution. When the Empress Cixi died in 1908, three-year-old Pu Yi became the Emperor Xuantong, but the Qing line was no longer strong enough to hold everything together.

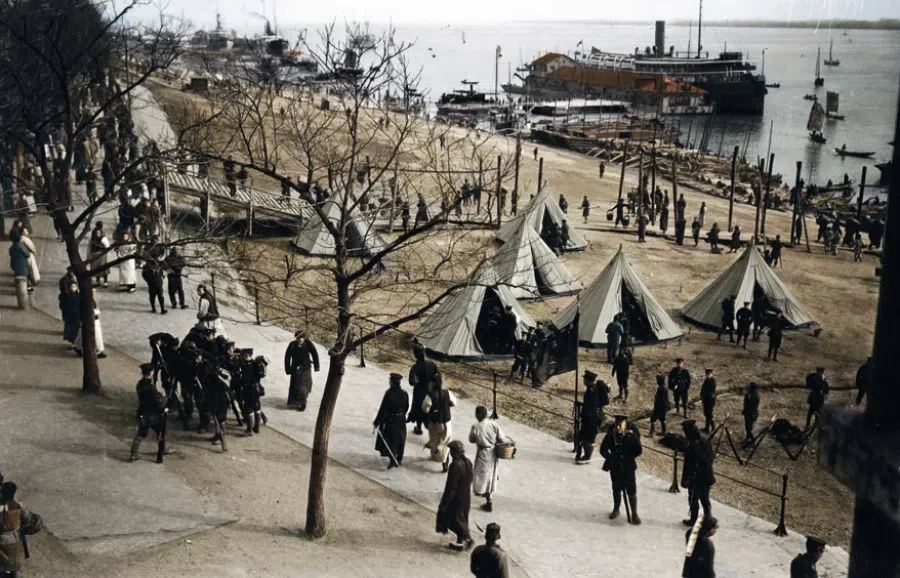

On 9 October 1911, the revolutionaries were exposed in Hankou. The leaders were arrested and executed the next day, triggering the revolutionary action to reach new heights, and kickstarting the major changes that happened between 1911 and 1912.

On that day, some of the New Army revolutionary recruits engaged in a fierce battle with the Qing soldiers at Wuchang. The revolutionaries attacked and captured the residence of Ruicheng, the Viceroy of Huguang. Ruicheng fled, leaving the Qing soldiers in chaos. The revolutionaries quickly took the cities of Wuchang, Hanyang, and Hankou in Wuhan, and established the Hubei military government with Li Yuanhong as the governor, and gave it a new name: the Republic of China.

Between October and December 1911, the Chinese and foreign media were all focused on Wuhan. The Wuchang Uprising stunned the Qing court, which quickly gathered its forces and deployed elite troops southward. The fighting between the revolutionaries and the Qing troops lasted from the latter half of October to late November. At first, the advantage lay with the revolutionaries, but when the main Qing forces arrived from the north, the revolutionaries retreated, and the Qing troops took Hankou. The revolutionaries, led by Huang Xing, retreated to Wuchang, where they were stuck in a deadlock with the Qing soldiers.

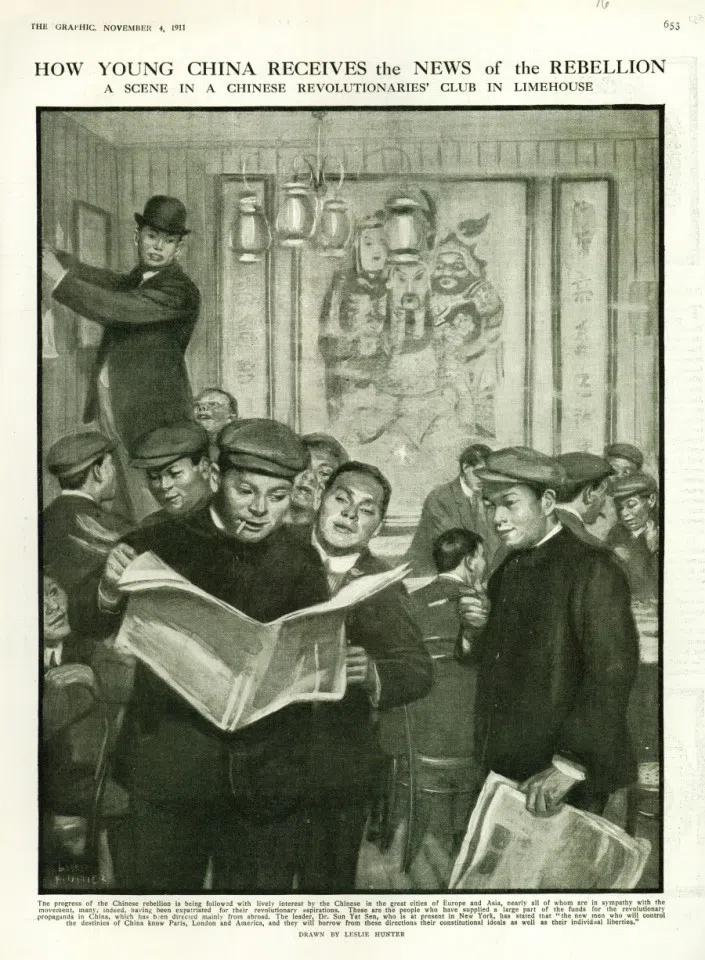

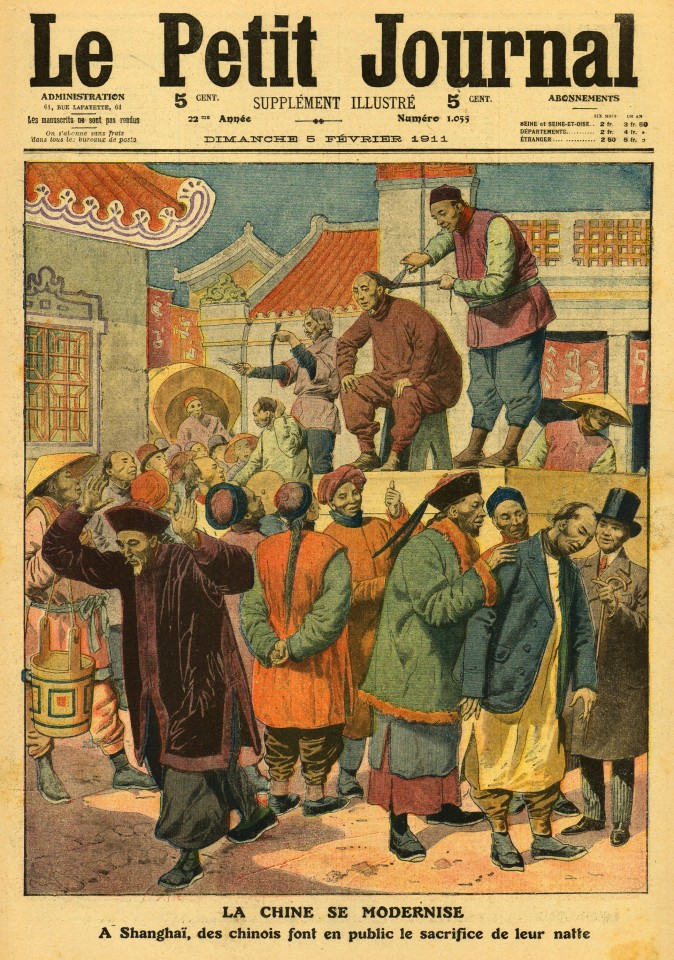

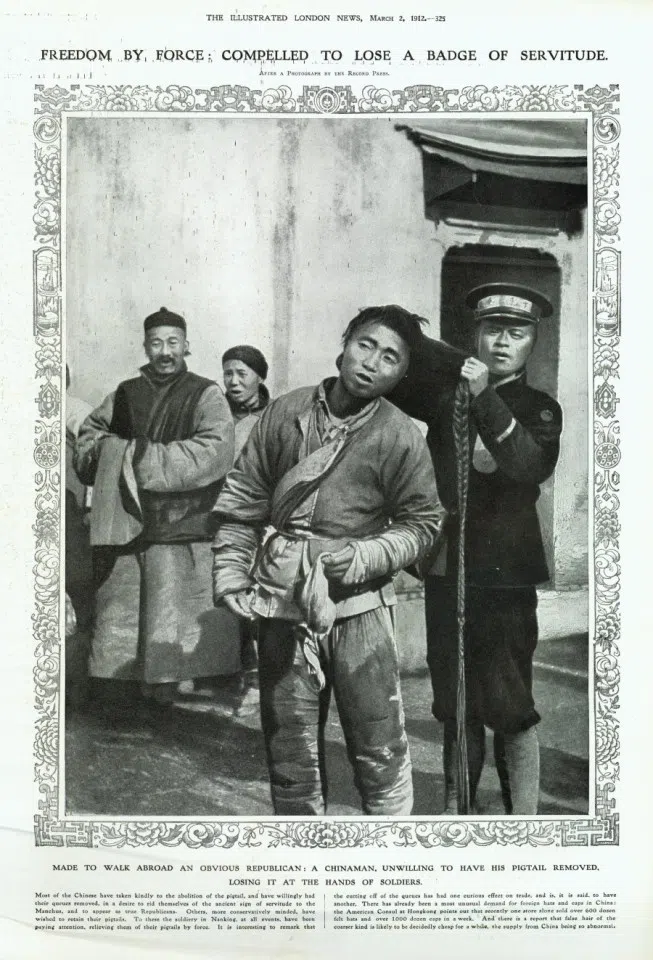

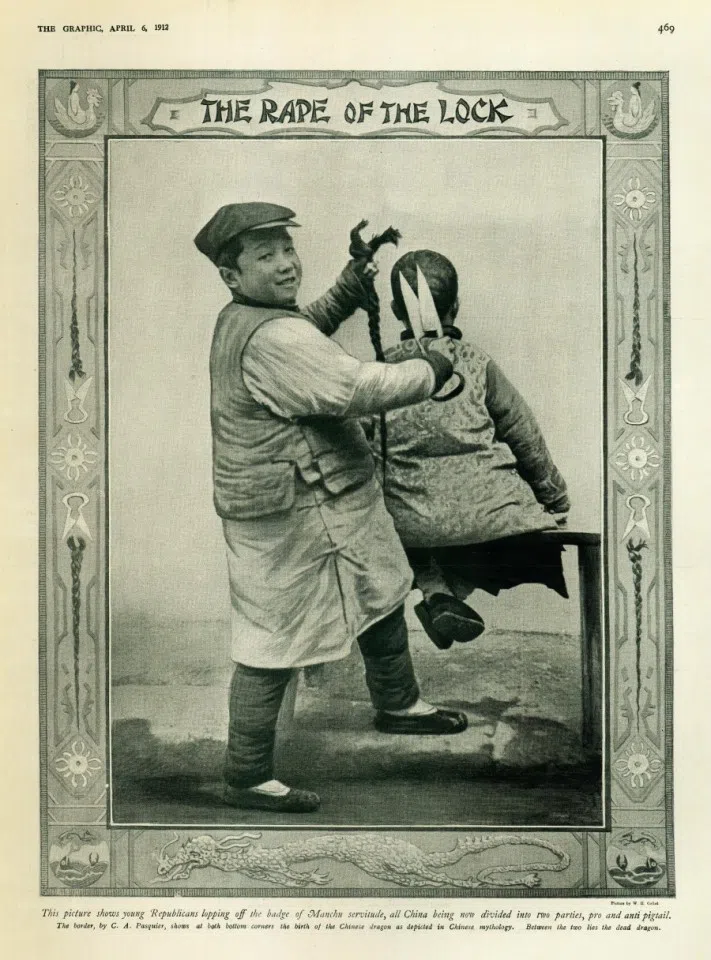

And while the revolutionaries were fighting, the various provinces responded in support. Hunan, Shaanxi, Jiangxi, Shanxi, Yunnan, Zhejiang, Guizhou, Jiangsu, Anhui, Guangxi, Fujian, Guangdong, Sichuan, all declared that they were no longer part of the Qing dynasty. The major newspapers in Europe, the US, and Japan reported developments, while the pictorials of the time gave coverage to both sides through depictions of scenes of burned cities and government offices, damaged railways, and fleeing civilians, although the sheer number of reports and images favoured the revolutionaries. This was true for practically all the Western reports on China, around the time of the Xinhai Revolution.

Sun Yat-sen's struggle

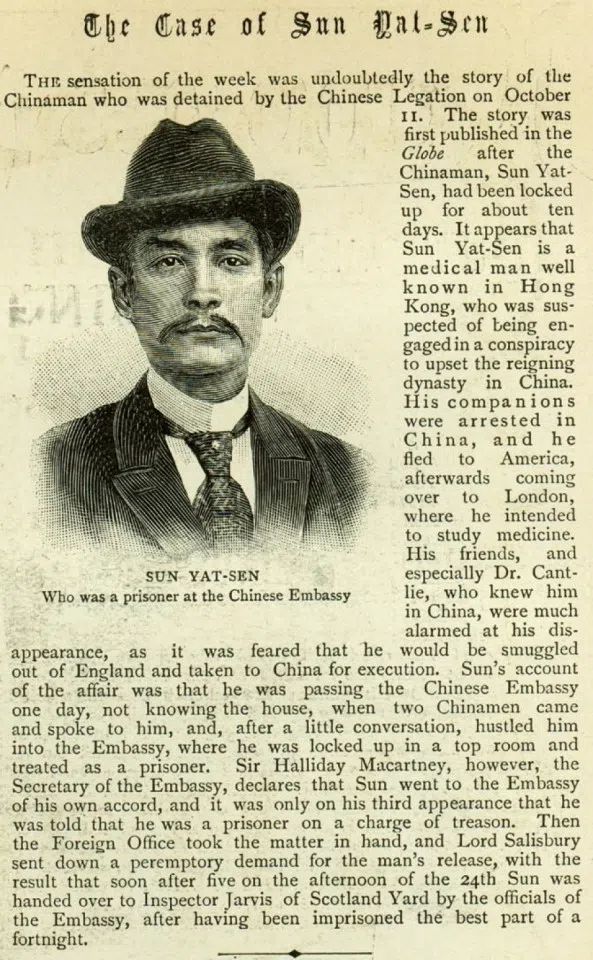

In his youth, Sun Yat-sen was influenced by the revolutionary Hong Xiuquan, and learned about modernisation through contact with Western culture, which planted in him the idea of overthrowing Manchu rule.

In 1894, Sun established the Xingzhonghui (兴中会, Hsing Chung Hui or Revive China Society) in Honolulu, Hawaii. Initially, the objective was to overthrow Manchu rule and restore a Han government. In 1905, Sun and Huang Xing established the Tongmenghui in Tokyo, which spread the revolution by attracting many Chinese youths in Japan. They sparked armed uprisings in China, while moving through different countries to gain international support for the revolution in China.

When the Wuchang Uprising broke out, Sun was in the US, giving speeches to raise funds. After he received the news, he continued on to Europe, to convince these foreign governments to support the revolution. On 24 November, Sun arrived back in Shanghai by ship. He moved on to Nanjing, and was elected by provincial representatives as the interim president of the Republic of China.

Around the same time, Yuan Shikai, the commander of the New Army tasked with suppressing the revolutionaries, took a two-pronged approach. On one hand, he threatened the Qing royals that if they did not step down, they would suffer the same tragic fate as King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution of 1789; on the other hand, he claimed credit from the revolutionaries for threatening the Qing royals.

Subsequently, the North-South Conference (南北议和) was held, and the infighting among the Qing royals intensified. Coupled with Yuan Shikai's manoeuvring, on 12 February 1912, the Emperor Xuantong abdicated, officially ending over 2,000 years of imperial rule in China.

As the north and south reached a consensus, Sun Yat-sen proposed his resignation. He was willing to work on building China's railways during peacetime, with Yuan Shikai as president of the Republic of China, to deliver a unified system. Sun resigned in February, but Yuan claimed to have much to do in the north and declined to go south to Nanjing to take office, remaining in Beijing instead. The capital of the Republic of China was thus moved northward.

The Wuchang Uprising happened quickly, but it was, in fact, the result of over ten years of hard work by Sun Yat-sen and the revolutionaries. The revolution itself was about removing Manchu rule and restoring the Han Chinese to their place.

After the revolution, the Tongmenghui became the Kuomintang, committing itself to bringing together the five ethnic groups - Hans, Manchus, Mongols, Huis, and Tibetans - adopting the five-colour flag to represent the Republic of China, and bringing the Chinese into the modern world.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)