Why China's once red-hot solar sector is cooling

Over the past year, capital from industries such as liquor, finance, real estate and the internet has been pouring into the new energy sector, driving up the valuations of solar energy stocks in China. However, the industry looks set to come back down to earth. Why is this so?

(By Caixin journalists Zhao Xuan and Manyun Zou)

In December 2021, a Zhejiang-based solar power facility provider raised about 5.6 billion RMB ($884 million) in its Shanghai STAR Market listing, more than ten times its target amount.

Hoymiles Power Electronics Inc. had planned to spend the proceeds on building power plants and upgrading equipment, according to its prospectus. But since its debut, the company has announced plans to use as much as 4.5 billion RMB of the windfall to buy financial products.

Hoymiles Power was just one of the Chinese solar energy companies that became an investor darling last year, as China ramped up its effort to achieve its bold green ambitions.

Two years ago, President Xi Jinping announced that China aimed to reach peak emissions before 2030 and become "carbon-neutral" within the following three decades, helping the photovoltaic (PV) sector take off.

The CSI Photovoltaic Industry Index - which tracks the shares of 50 major listed domestic solar energy companies - rocketed 45% from 4 January to 30 December, reaching a total market value of 2.8 trillion RMB.

After expanding by a blistering 110% in 2021, the revenue growth of China's PV industry will slow to around 40%.

Over the past year and a half, capital from industries such as liquor, finance, real estate and the internet has been pouring into the new energy sector, driving up the valuations of solar energy stocks, an investment bank analyst said.

As of the end of December, PV product giant Longi Green Energy Technology Co. Ltd. reached a market cap of 440 billion RMB, Trina Solar Ltd. touched 160 billion RMB, and JA Solar Technology Co. Ltd. hit 150 billion RMB, all surging four to eight times from their low point in 2020. Silicon supplier Tongwei Co. Ltd. also saw its market value jump four times to 200 billion RMB.

However, the industry looks set to come back down to earth. After expanding by a blistering 110% in 2021, the revenue growth of China's PV industry will slow to around 40%, analysts from Citic Securities Co. Ltd. forecast in a research note published in December.

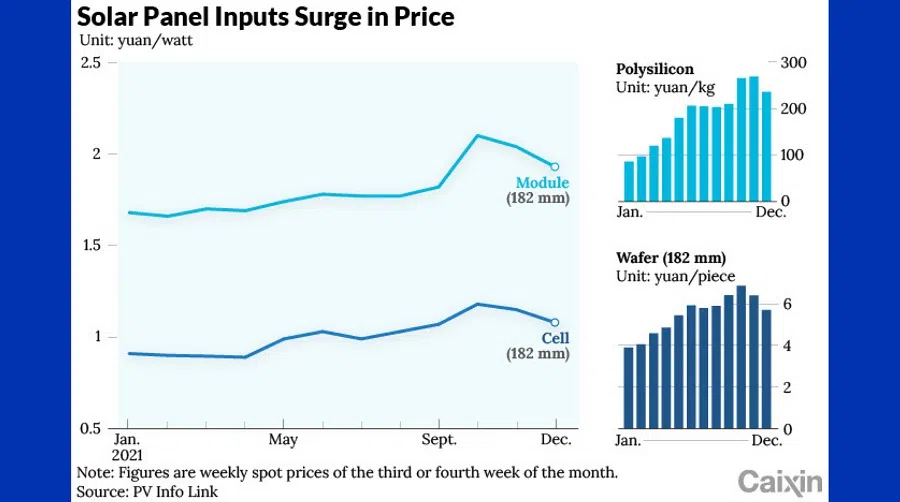

Government policy is one factor, but a more direct reason is that production capacity from the midstream of the industry on up, has outrun output of its main raw material - polysilicon - causing price rises down the industrial chain that now leave the profitability of new solar power plants in question.

Outrunning the supply

According to Lü Jingbiao, the deputy director of the Silicon Industry of China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association, the blame for the soaring price of polysilicon rests with the rapid build-up of capacity in the middle stream of the industry.

"We have enough polysilicon to bring up the solar power capacity in 2021, but we don't have enough polysilicon to satisfy the increasing capacity for silicon wafers and modules," another source inside the module company agrees.

Polysilicon is the raw material used to make silicon wafers, which are combined together into PV cells. The cells then make up PV modules, also known as the solar panel.

Therefore, more than 90% of the market's silicon had already been booked in early 2021, leaving small or new producers scrambling to buy the remaining 10%, pushing up prices for everyone.

Just last year, wafer supplier Longi increased its production capacity by 24% to 105 gigawatts. Another giant of the business, Tianjin Zhonghuan Semiconductor Co. Ltd., boosted its capacity by 56% in 2021 to 85 gigawatts, and raised its 2023 target to 135 gigawatts.

According to Lü, there were 580,000 tonnes of polysilicon available in the world last year to produce 200 gigawatts of PV modules, which could create 160 to 170 gigawatts of installed capacity. However, now that silicon wafer manufacturers have expanded their capacity, they "are going to produce 400 gigawatts, which is already twice the production capacity of polysilicon."

The contracts between midstream producers and silicon suppliers usually set an annual volume - for three to five years - but allow for price changes monthly, Lü says. Therefore, more than 90% of the market's silicon had already been booked in early 2021, leaving small or new producers scrambling to buy the remaining 10%, pushing up prices for everyone.

In the week of 22 December, polysilicon was selling for an average price of 236 RMB per kilogramme, a 174% surge from prices earlier last year, according to market research institute PV InfoLink. The spot price of wafers also jumped 46% last year to reach an average price of 5.7 RMB a piece.

And those price increases do not bode well for downstream solar power plant operators.

"The current cost makes nearly half of solar energy projects in China unprofitable," says a source from a PV module company.

Pulling back

In 2021, China added 53 gigawatts of installed solar power capacity, falling short of the China Photovoltaic Industry Association's (CPIA) prediction for between 55 and 65 gigawatts, figures from the National Energy Administration show.

The lower-than-expected amount shows that downstream power plant operators are already feeling the surge in raw material prices, Qian Jing, the vice president at New York-listed PV module provider JinkoSolar Holding Co. Ltd., says at a CPIA meeting in mid-December.

Last year was already a hard time for solar power plants, because it was the first year for China to set grid-parity prices for renewable power, which deprived producers of governmental subsidies and left them with smaller profit margins, a source from a state-owned electricity producer tells Caixin. "If I know I am going to lose money, I'd rather halt my project," the source adds.

As demand slows, module suppliers tend to turn to price cuts. In November, the Shanghai-listed Longi slashed its module prices by as much as 15%, followed by Shenzhen-listed Zhonghuan, which also lowered its product prices twice in a single month.

The price cuts by the two industry giants knocked the once-skyrocketing prices of silicon wafers down from 270,000 RMB per tonne to 230,000 RMB per tonne in December alone, a sign that the industry may resort to deeper cuts in the future due to oversupply concerns.

With lower prices, "the world's largest module manufacturer Longi will not only clean out its inventory, but can also squeeze out new competitors," says Hu Dan, a senior analyst at information provider IHS Markit Ltd.

...the PV industry will undergo a "painful" reshuffle for five to ten years, as it is expected to soon experience excessive supply problems.

Last year, industry newcomers such as Shuangliang Eco-Energy Systems Co. Ltd., Wuxi Shangji Automation Co. Ltd. and Beijing Jingyuntong Technology Co. Ltd. planned for combined production capacity of nearly 189 gigawatts of wafers.

"When these newcomers finally start production, they may realise the business is not profitable anymore, even though they have already poured money into land and facilities," says an unnamed senior brokerage analyst.

Clouds on the horizon

CPIA deputy secretary-general Liu Yiyang estimates that the PV industry will undergo a "painful" reshuffle for five to ten years, as it is expected to soon experience excessive supply problems.

The sector suffered a similar price war about 11 years ago, during which PV companies were able to expand their capacities thanks to generous subsidies, but later ran into trade barriers that shrank the market. One of the world's largest solar-panel makers at that time, Suntech Power Holdings Co. Ltd., ended up in bankruptcy restructuring due to its billions of debt.

Solar energy companies that managed to live through last year's grid-parity price policy change have proven their profitability, further assuring the capital market that they are a good investment, the International Institute of Green Finance of the Central University of Finance and Economics writes in a research note published in October.

But it is unlikely the PV sector will have another bumper year like 2021, because all the policy incentives in the 14th Five-Year Plan, which covers 2021 to 2025, were released last year.

"In the long run, the solar energy sector will keep growing for sure, but individual companies may be subject to risk," says Peng Peng, secretary-general of the China New Energy Assets Investment and Financing Platform.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as "In Depth: Why China's Once Red-Hot Solar Sector Is Cooling". Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)