Wintersweet scents in Jiangnan

Cheng Pei-kai grows despondent on a dark day of winter in Suzhou, but perks up instantly with one whiff of wintersweet's enigmatic scent.

The four seasons of Jiangnan are clearly defined - flowers bloom in Spring, the roundest moon appears in Autumn, the rainy season comes in Summer, and snow falls in Winter. There seems to be something unforgettable and alluring in each season - except perhaps in the early winter when the last of autumn leaves fall and trees become barren. Alas, Nature is not spared from the harshness of winter. Instantly, it is as if many of life's moments turn bleak. The bone-chilling winds - like a shaky razor hovering dangerously between one's cheek and neck - send shivers down my spine.

I would occasionally visit Suzhou in such a season, often feeling as if I had picked one of the most awkward times of the year to visit. Walking around the residential area outside my apartment, trees and plants that were once full of life would lie curled up, shivering in the cold. I would grumble to myself that there were awful days, even in beautiful Suzhou. No wonder Jiangnan literati from the 1930s could hum tunes like "flowers don't always bloom, and beautiful sceneries don't always last" when expressing their melancholy during the dull winters - they probably witnessed the changing of the seasons, and had an outpouring of emotions.

On one occasion, I became increasingly despondent as I lugged my suitcase around in waning daylight. Right at that moment, I detected a delicate fragrance coming from the shrubs growing by the walls. It was barely there, yet distinct, like a fleeting glimpse of ancient beauties gliding past inner chambers.

International metropolises like New York, London and Hong Kong boast rare botany from five continents, but none with such a refreshing and sophisticated fragrance such as this. Following the scent, I found, as I suspected, a wintersweet shrub at the corner of the wall. Its yellow leaves had lost their vitality and fallen to the ground as the winter winds blew. Yet, vibrant wintersweet flowers peeked out of their stems like clusters of small bells sculpted from yellow wax. That's right. This was the unmistakable scent of wintersweet flowers - the last remaining breath of fresh air in this cold, dark, chilly winter of Jiangnan.

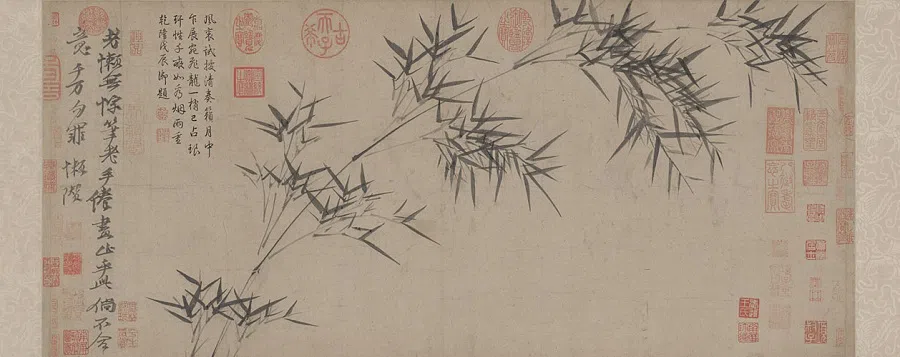

In the past, I've always thought that the wintersweet belonged to the same plant species as the plum flower - except that its colour paled in comparison to its other vibrant siblings and cousins that were worthier of admiration. It is like an ugly duckling amidst a beautiful flock of swans - a total misfit. Yet, unassuming as it may be, the delicate fragrance that a wintersweet emits is incredibly refined. It elicits the kind of emotions that the ink paintings of Ni Yunlin (a Chinese painter during the Yuan and early Ming periods) evoke, and is a shining example of the highest form of aestheticism that draws endless adoration. I only came to know later that the wintersweet did not belong to the same family as the plum flowers.

According to plant taxonomy, the wintersweet belongs to the Chimonanthus genus, while the plum flower belongs to the Prunus genus. As both the wintersweet and the plum flower bloom in snowy winters, they have long been misunderstood as coming from the same plant species, differing only in the shape of their flowers. In actual fact, ancient Chinese Materia Medica scholars have clearly recorded the difference between these two species. It's just that we have failed to pay attention to what was written and didn't bother to dive deep into it. We often take words at face value or gullibly accept folklore, passing wrong information around the community via word-of-mouth, and thus lose the basic ability of discernment.

According to Li Shizhen's Compendium of Materia Medica (《本草纲目》), "wintersweet (蜡梅), also known as the yellow plum flower... does not belong to the Prunus genus, but got its name as the season in which it blooms and the scent it emits, are similar to the plum flower. It also has a beeswax colour". The Mirror of Flowers (《花镜》), a book on horticulture written by Chen Haozi in the early Qing Dynasty, affirms this: "The wintersweet, also known as the yellow flower, does not belong to the Prunus genus. It got its name as it blooms at the same time as the plum flower, emits a similar scent, has a beeswax colour, and also blooms in the last month of the Chinese lunar calendar."

Speaking of blooming in the last month of the Chinese calendar (腊月), this is also another difference between the wintersweet and the plum flower. The wintersweet blooms early around the time of the winter solstice. On the contrary, plum flowers often bloom later, nearing the end of the last month of the Chinese calendar. Perhaps because of the season in which the wintersweet blooms, its name is commonly written in two ways: according to its Chinese name lamei (蜡梅, where 蜡 refers to "wax"), or lamei (腊梅, where 腊 refers to "last month of Chinese calendar").

Qu Dajun, a Guangdong poet during the late Ming and early Qing Dynasty, wrote a poem entitled Plum Flower (《梅》): "咫尺梅关雪不来,梅花开罢腊梅开。炎州十月春如海,处处飞香半是梅。" Loosely translated, the stanza reads, "Snow has not fallen on Mei Pass. The plum flowers are in full bloom, slowly awakening the wintersweets' first blooms. The tenth month in the southern regions resembles the vibrant springtimes. Floral fragrances fill the air, with vague hints of plum flower scents present." The lines depict the blooming of plum flowers in the Lingnan Mei Pass (岭南梅关) region ahead of the wintersweet's blooming. I'm unsure if Guangdong's weather conditions were different, or if Qu Dajun had mixed up the seasons in which these two flowers bloom. In any case, Qian Hengsheng, who lived during the Qing Dynasty, got the seasons right in her poem, Wintersweet (《腊梅》): "晓风帘自卷,春信占梅先。腊蕊雪中破,清香小院前。" Roughly, she says, "A gush of morning breeze sweeps the curtains open. The wintersweet is the first to report the dawn of Spring; its first blooms emerging from the snow, and refreshing scent wrapping the courtyard with open arms."

Finally, Song dynasty poet Zheng Gangzhong says it best in his poem, Wintersweet (《腊梅》): "缟衣仙子变新装,浅染春前一样黄。不肯皎然争腊雪,只将孤艳付幽香。" The lines read, "Snow-white fairies don new dresses, dyed a golden yellow before Spring arrives. It fights not to be the whitest against the Snow White, only to let its sophisticated beauty shine through its elegant fragrance."