Russian academic: Whose ideology will rule an emerging 21st century world?

Amid a changing global order, Russian academic Artyom Lukin analyses the different ideologies of the US, China and Russia and explains why it would be hasty to lump Russia and China in one camp or to dismiss the similarities between the US and Russia. In the end, the ideology that rules the emerging new world may not even be that of any of the three countries.

It is increasingly clear that, in terms of hard power, a new edition of bipolarity is emerging before our eyes. Despite the decline in its relative power, the US will continue as a superpower for at least the next few decades. Yet Washington will have to share the top spot in the hierarchy of material - economic plus military - power with Beijing. Barring a major cataclysm derailing its national development, China looks set to become a full-fledged superpower within the next decade or so.

Realistically, there are no contenders in the running to question a US-China bipolarity. The Ukraine crisis, culminating in a war that is ravaging Europe, has dealt a blow to whatever hopes the EU and Russia might have nurtured of becoming 21st century superpowers. Post-Ukraine, the best they can hope for is to stay as meaningful geopolitical and geoeconomic players. As for India, it continues to be beset by multiple domestic issues that hobble New Delhi's ambition to reach the superpower status in any foreseeable future.

The geopolitics of the coming future world will be defined not only by the distribution of material capabilities among the major players - the so-called "polarity" in the international relations theory parlance - but also by the ideological landscape.

As opposed to hard power attributes such as GDP or the number of aircraft carriers, ideas and their sway is something that is far more difficult to quantify and measure. Still, it is hard to deny that ideological competition is making a comeback in world politics.

As things stand in the early 2020s, there are three major ideological systems competing for human minds. They are represented by the world's most active geopolitical players - the US, China and Russia.

... there have not been so few liberal democracies in the world since 1995. In addition, at present, only 13% of the world's population live in this least populous regime type.

'Wokeness' and the decline of liberal democracy

The US, the leader and hegemon of the collective West, represents the ideology of liberal democracy and market capitalism. This ideology continues to evolve. Its newest mutation is known as "wokeness" or an acute awareness of social injustice. In wokeness, the two main ideological strands of modern West that have their origins in the European Enlightenment - liberalism and communism - have collided after a bitter internecine feud and reunited.

When the opponents of "woke" compare it to radical Communist Bolshevism, it is not without reason. In its fight against structural oppression, woke is ultimately about destroying social hierarchies for the sake of justice - and at the expense of order. In extremis, its struggle for equity and equality leads to universal homogenisation, destroying the diversity of social and even physical identities.

It is not clear, though, if wokeness is a long-term trend that will come to dominate the West or is merely a short-term fad, an evolutionary dead end that will be displaced by other varieties of liberalism.

Western-style liberalism is certainly not dead, but the past decade has not been kind to liberal democracy. According to findings from the V-Dem Institute's "Democracy Report 2022: Autocratisation Changing Nature?", the number of the world's liberal democracies peaked in 2012 with 42 countries. The report adds that there are only 34 in 2021 and there have not been so few liberal democracies in the world since 1995. In addition, at present, only 13% of the world's population live in this least populous regime type.

China and Russia are often lumped together as "fellow autocracies" opposing Western liberal democracy. The truth is, the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Kremlin stand for very different ideological models

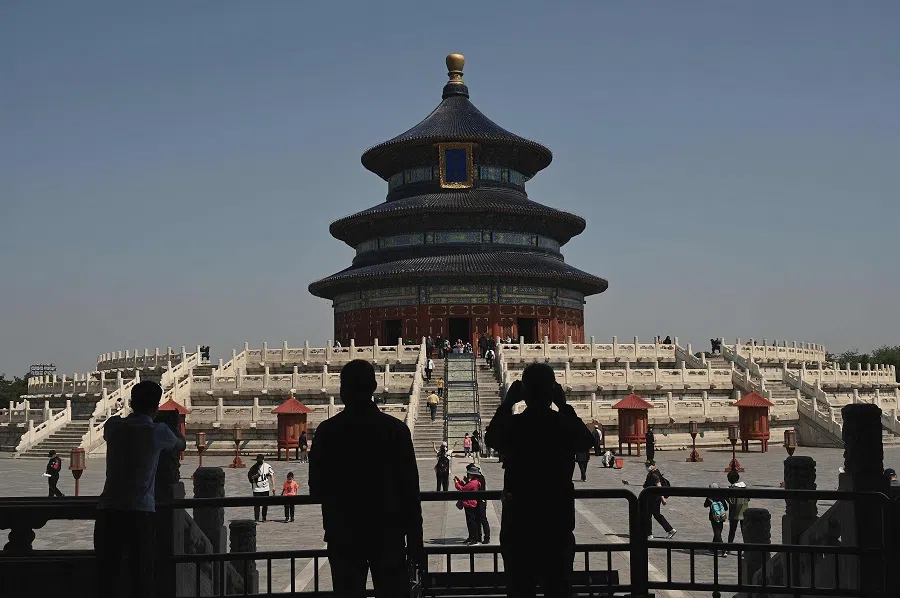

China and Russia are often lumped together as "fellow autocracies" opposing Western liberal democracy. The truth is, the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Kremlin stand for very different ideological models. China's is a synthesis of Marxist-Leninist-Maoist socialism blended with traditional Chinese ways of governance, such as Confucianism and Legalism, all boosted by 21st century digital technology.

The West increasingly fears China not only due to the growth in Beijing's economic and military power, but also because modern China's hugely successful development record seems to validate the CPC's ideology. Whether you like it or not, it is difficult to contest Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi's recent statement that "more and more people around the world admire the achievements of the Chinese people under the leadership of the CPC".

It is true that China lacks individual freedoms, but do humans really need freedom, the burden of which is often unbearable for the average person? The famous monologue of the Grand Inquisitor in Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, which posits the contradiction between welfare and freedom, could well belong to someone in the highest echelon of the modern-day CPC: "They will understand themselves, at last, that freedom and bread enough for all are inconceivable together, for never, never will they be able to share between them!"

Does China want to export its ideology beyond its borders? This is a crucial question, but one which is extremely difficult to answer right now. There are ambiguous signals coming out of Beijing in this regard. It might well be that the Chinese leadership has yet to decide whether China should do so.

Many rulers and elites of the empire were, and are, non-Russian. Many key figures around Vladimir Putin are not ethnically Russian.

Russia and China have different ideologies and worldviews

To begin to understand Russia's ideological model, one needs to get rid of two big misconceptions about Russia.

The first mistake is that Russia is a nation-state of ethnic Russians. In fact, Russia has never been a Russian nation-state. Rather, it has been a multi-ethnic Eurasian empire. The empire was born in Kiev (or Kyiv) in the 9th century, with direct involvement of the Varangians from Scandinavia. The empire's capital then moved, consecutively, to Vladimir, Moscow, Saint Petersburg and back to Moscow.

Many rulers and elites of the empire were, and are, non-Russian. Many key figures around Vladimir Putin are not ethnically Russian. For instance, Russian Defence Minister Sergey Shoigu is a Tuvan, while the powerful warlord Ramzan Kadyrov is a Chechen. As another example, in the 19th century, Russia subjugated Dagestan in the long and brutal Caucasian War. Now the Muslim region of Dagestan is the largest supplier of troops for the Ukraine war. It is followed by Buryatia, another ethnically non-Russian region.

As any true empire, the Russian Empire, including in its current reincarnation of the Russian Federation, is not that much Russian, at least not ethnically. It is founded upon the idea of power per se, rather than on the principle of ethno-nationalism.

Rather than the communist Soviet Union, Putin's preference seems to be the old czarist Russia...

The other misconception is that Vladimir Putin seeks to revive the communist Soviet Union. In fact, the current Russian ruler is very ambivalent about the Soviet model and outright negative about Communist ideology. Rather than the communist Soviet Union, Putin's preference seems to be the old czarist Russia: a vast continental autocracy relying on "healthy conservatism" and "time-tested tradition" - marker phrases that Putin uses a lot.

Putin's system is antithetical to revolutionism. The Russian leader openly detests revolutions as evil: "Russia's political system is ... evolving steadily so as to prevent any revolutions. We have reached our limit on revolutions." In the same vein, the Russian Orthodox Church Metropolitan Tikhon (Shevkunov), who is one of Russia's most influential ideologues and rumoured to be Putin's spiritual confidant, has been incessantly warning about the dangers inherent in revolutions.

Similar to Hollywood epics exploiting medieval narratives, much of the appeal of "the Putin universe" may be drawing upon the themes of power, masculinity, hierarchy and miracle.

Putin's words often sound as if they are taken from Edmund Burke's "Reflections on the Revolution in France". That's a major reason why the ideology of modern Russia appeals to some right-wing conservatives in Europe and North America who see Russia as the last major state that adheres to the values of what used to be the European Christian civilisation.

Putin's Russia has another advantage. It is appealing aesthetically. For the Putin state, order is prior to justice. Justice, especially the unlimited justice of woke, is often messy and unseemly. Order, especially a hierarchical one, has its own powerful aesthetics. Think of the beauty found in the worlds of The Lord of the Rings or Dune. Similar to Hollywood epics exploiting medieval narratives, much of the appeal of "the Putin universe" may be drawing upon the themes of power, masculinity, hierarchy and miracle.

Finally, a big attraction of the Russian ideological model is its perceived anti-Americanism. The hard core of the global community of Russia sympathisers are not people who like Russia per se, but, rather, those who hate America and see Russia as an essential counterforce to the American Empire. In other words, their sympathy for Russia derives from their hatred of the US. The Ukraine war has hardly made them anti-Russian. On the contrary, some of them may have become even more pro-Moscow since they view the Ukraine crisis as a proxy war between Russia and the US-led West.

Both America and Russia are deeply irrational polities, very much determined by religious faith and the belief in the transcendental.

Russia, closer to the US than one might think

It may seem counterintuitive, but the US and Russia share one foundational trait that sets them apart from China and makes them alike. Both America and Russia are deeply irrational polities, very much determined by religious faith and the belief in the transcendental. Both the US and Russia are based on Abrahamic messianic monotheism, considering themselves God's chosen people.

In a sense, the contemporary confrontation of America and Russia is a continuation of the Great Schism of 1054 whereby the Christian Church split into Western and Eastern Christianity. Europe is now largely atheist. But the zeal of Western Christianity has moved to America. For its part, Russia is the heir to the Byzantine Empire and considers itself the main guardian of the Eastern (Orthodox) Christian faith. The fight over Ukraine is also a crucial battle over dominance in the Christian world.

That the Chinese do not believe in God reduces the likelihood of major violence in Asia and the Pacific.

Unlike America and Russia, China's sense of exceptionality is not tinged with religious overtones. China is a godless civilisation. Instead of the search for transcendental God, modern China pursues down-to-earth rationality. There may be epochs in human history that favour messianic societies based upon the mystical belief in God and miracles. But then there are eras advantaging civilisations that are less spiritual, more rational, and perhaps more boring. As a rule, such polities are less aggressive, if only because they lack religious zeal and proselytism that drives a civilisation to destroy anyone who refuses to convert into its faith.

That the Chinese do not believe in God reduces the likelihood of major violence in Asia and the Pacific. Measured against the US and Russia, modern China comes across as a force of sanity and sobriety that prioritises economic development and the preservation of human lives. It remains to be seen if we have entered an era that favours reason over religious faith. If this is truly the case, that will be China's era.

To have a chance at world domination, Islam needs a powerful carrier state. Could Russia become one in the long term?

The fourth way

Apart from the ideological models represented by the US, China and Russia, there is also the fourth ideology with ambitions to become universal and dominate the world. It is Islamism. This religion-ideology is now disembodied, lacking a "carrier state".

"The Islamic State/ISIS", which had tried to establish itself as the main base for creating a universal Islamic caliphate, was promptly crushed by collective efforts of the major powers. It is remarkable - and hardly by chance - that Moscow, Washington and Beijing were able to come together against the Islamic State. Was their unity motivated by the shared fear of a powerful ideological rival?

It may be premature to write off Islam and Islamism as an ideological contender. To have a chance at world domination, Islam needs a powerful carrier state. Could Russia become one in the long term?

If this question sounds insane, consider that the Muslim population of Russia now stands at 25 million and the share of Muslims in the population of Russia is steadily growing. Consider also that Ramzan Kadyrov, the charismatic strongman chief of the Muslim region of Chechnya, is beginning to be mentioned as Putin's possible successor. After all, Islam is just as Abrahamic as Christianity, which is still Russia's main religion.

With the coronavirus pandemic and now the Ukraine war, the world may have entered a long period of turbulence. Climate catastrophes and famine are lurking perilously close. Despite all its horrors, the new epoch may become a magnificent illustration of Hegel's thesis that ideas are what matter most. But the validity of ideas must be tested in the material world. And what can be more material than war and other calamities? Ideas that do not pass the test are bound to be discarded - perhaps along with the very states that embody these ideologies.

Related: How Putin became trapped by his own authoritarianism | Emperor Putin's missed opportunities and delusions | How the Ukraine war will reshape the EU's approach to China and Indo-Pacific | When a country needs to choose between realism and idealism | Lessons from Russia-Ukraine war: The UN of 1945 must be reformed

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)