Will Indonesia establish a University of Confucianism?

The Pancasila (meaning Five Principles) forms the backbone of Indonesian state ideology. Religious freedom is assured through the first principle - "Belief in One Supreme God". Although there is no specific religion that one needs to follow, the Indonesian government officially recognises only six religions, namely Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism.

In theory, these religions enjoy equal status and treatment, and are included in the national religious education curriculum administered by the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Confucianism, however, was the last to be included in the curriculum and is therefore the least developed. Qualified teachers of Confucianism have been greatly lacking.

The recently announced plan by the Joko Widodo administration to establish an International State University of Confucianism in Bangka Belitung province will definitely help enhance the quality of Confucianism education in the country.

From Kong Jiao Hui to Agama Khonghucu: Localisation of Confucianism

In 1965 - before Suharto came to power - Indonesia recognised Confucianism as one of the six official religions (agama). But before December 1963, Confucianism was called Khong Kauw Hwee (the Hokkien pronunciation of Kong Jiao Hui 孔教会)which means "Confucian religion association".

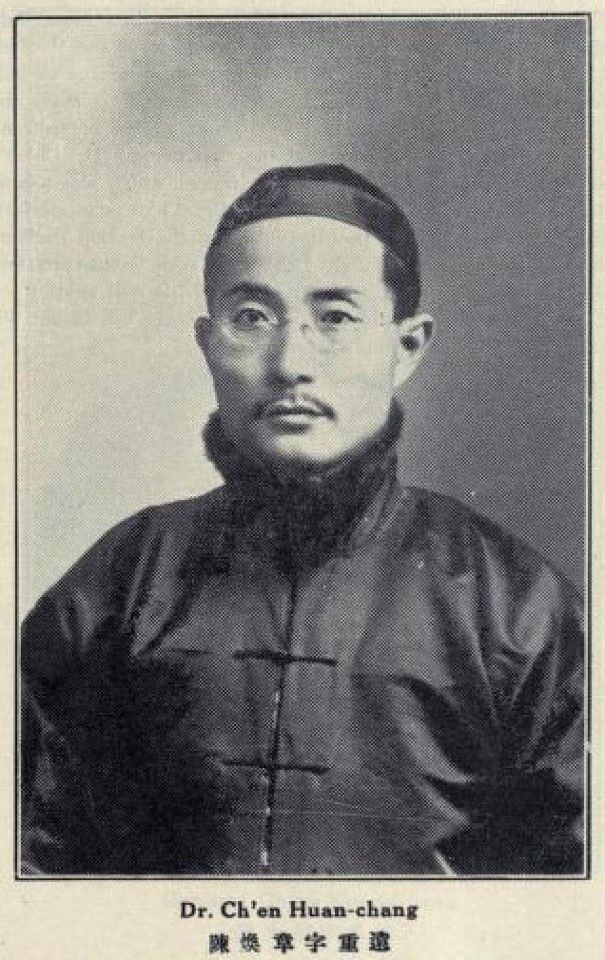

The establishment of the Khong Kauw Hwee was linked to the Confucius Revival movement in mainland China under the leadership of Kang Youwei(康有为)and his disciple Chen Huanzhang(陈焕章). In 1912, Chen set up Kong Jiao Hui in Shanghai. The Indonesian version was established in 1918 in Solo (Surakarta) by Peranakan Chinese and it had no formal links with the Kong Jiao Hui in China.

Over time, Confucianism in Indonesia was influenced by Christianity, Islam and more importantly, the Indonesian language and culture - so much so that by 1963, Confucianism was no longer referred to as "Khong Kauw" but "Agama Khonghutju" (or "Agama Khonghucu" after 1972).

Prior to this, there was a Confucianist movement in Java represented by the Tiong Hoa Hwee Koan (THHK) organisation in Jakarta, which was established in 1900. Although THHK promoted Confucius teachings, it never institutionalised itself as a religious organisation. Instead, it functioned as an educational association promoting Chinese-medium schools, and by 1928, its focus had shifted from Confucian teachings to Chinese nationalism. Nevertheless, it should be noted that some of the concepts of Confucianism in Indonesia were developed during this time by Lie Kim Hok of the THHK, and these were later adopted by Khong Kauw Hwee.

Over time, Confucianism in Indonesia was influenced by Christianity, Islam and more importantly, the Indonesian language and culture - so much so that by 1963, Confucianism was no longer referred to as "Khong Kauw" but "Agama Khonghutju" (or "Agama Khonghucu" after 1972). Up until 1965, during the Sukarno era, Confucianism was recognised by the Indonesian government as one of six official religions.

Soon after, the 930 movement (G-30-S) in 1965 caused the downfall of Sukarno, the dissolution of the Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia, or PKI) and the rise of General Suharto. According to the official version of history, the 930 movement was a coup attempt initiated by the PKI. Since communists were seen as atheists, the new regime considered anyone not following any religion to be a communist or a supporter of communism. They, therefore, required all Indonesians to profess a religion.

Suharto era: Religion or not?

In 1967, Gabungan Perkumpulan Agama Khonghucu Se-Indonesia (the Indonesian name of Khong Kauw Hwee that was adopted in December 1964) became the Majelis Tinggi Agama Khonghucu Indonesia (Indonesia's Supreme Council of the Confucian Religion, abbreviated as Matakin).

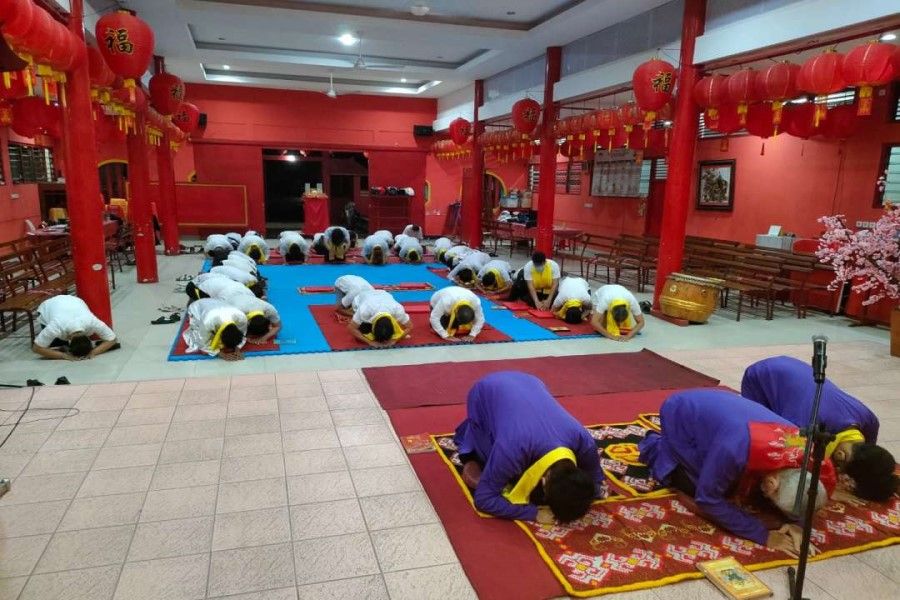

This entailed the formalisation of Confucianism as an institutionalised religion and required the enshrining of components common to other officially recognised religions in Indonesia, namely having one Supreme God (Tian or Thian 天), a prophet (Khonghucu or Kong Zi 孔子), a religious text (Su Si or Kitab yang Empat), a Confucian church called Litang (Lithang 礼堂), and priesthood (three categories of Confucians - Kauw Sing (教生), Bun Su(文师)and Hak Su(学师).

This remodelled Confucianism in Indonesia into an organised religion (agama), conforming to the first principle of the Pancasila - belief in one Supreme God. A similar transformation and Indonesianisation also occurred in the case of Buddhism. As Buddhism did not originally have the concept of one Supreme God, it only became an organised religion (agama) by adopting the concept of Adi Buddha as the equivalent of the Supreme God. Many Chinese Indonesians, especially the Indonesian-speaking Peranakan Chinese, have become adherents of Agama Khonghucu in order to retain their Chinese identity.

... in perceiving Confucianism as an obstacle to the assimilation of the Chinese Indonesians, [the government] decided to de-recognise Confucianism, arguing that Confucianism was not a religion even in China.

When the Suharto government first came to power, it wanted to mobilise all religious forces to combat the "atheist" PKI. Therefore, Agama Khonghucu was embraced. Nevertheless, in the 1977 general elections, Golkar won another landslide victory, indicating that the Suharto government had consolidated its power and no longer needed the support of Agama Khonghucu followers. The government went for total assimilation, and in perceiving Confucianism as an obstacle to the assimilation of the Chinese Indonesians, decided to de-recognise Confucianism, arguing that Confucianism was not a religion even in China. In February 1979, the Matakin had to cancel its congress after failing to gain a permit for gathering.

Followers of Agama Khonghucu now chose to reflect themselves in their Indonesian identity cards as professing Buddhism. In 1995, towards the end of the Suharto rule, some Confucianists started to rebel against the government's decision. One young couple even sued the chief of East Java Civil Registration Office in Surabaya for his office's refusal to register a Confucian marriage. The high-profile court case attracted national attention, including that of Abdurrahman Wahid (also known as Gus Dur) - then the chairman of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) - who was sympathetic to the followers of Confucianism. However, the court concluded in favour of the chief of Civil Registration Office.

Despite the derecognition of Confucianism, the Matakin leadership managed to maintain good ties with the moderate Muslim community such as the NU, so much so that towards the end of the Suharto rule, Matakin was allowed to hold its 1998 annual congress at a hall within the Ministry of Religious Affairs office. The hall was usually reserved for Muslim pilgrimage gatherings.

Private college to International State University of Confucianism?

Only after the fall of Suharto did Agama Khonghucu become officially recognised again. Nevertheless, the number of Confucianists has drastically declined. In 1971, the Indonesian census showed that only 0.7% of the Indonesian population was registered as Confucianists. In the 2020 Census, the number had dropped even further, to 0.05%.

Since the era of Reformasi, Matakin has become active again. The Ministry of Religious Affairs has also begun to pay attention to Agama Khonghucu, including preparing textbooks on the religion. However, the long suppression has led to a shortage of well-researched textbooks and qualified teachers.

In 2013, towards the end of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono's presidency, it was reported that the plan to establish a Confucian university was mooted. Nothing materialised, however, and it was only during the Joko Widodo presidency that the plan resurfaced. It has however encountered opposition from conservative and radical Muslims.

... it is difficult to assess if the college will become a major institution. However, once the International State University of Confucianism is established, the quality of Confucian education in Indonesia should improve.

Despite the opposition, Chinese Indonesians, especially the Peranakan Chinese, set up a foundation to establish a privately funded college of Confucianism (Sekolah Tinggi Khonghucu Indonesia, or STIKIN) to train and churn out qualified religious teachers in Confucianism. Although their initial plan to establish STIKIN in Semarang failed, they were able to obtain a permit to build the college in Purwokerto, Central Java. The secretary-general of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, Nizar Ali, attended the inaugural ceremony in February 2021.

This private college is headed by Suharjono Tan, a Chinese Indonesian. Currently, it has only 38 students, and it is difficult to assess if the college will become a major institution. However, once the International State University of Confucianism is established, the quality of Confucian education in Indonesia should improve. The prestige of such a university will likely attract more and better resources.

The initiative to establish such a university shows that the Indonesian government is moving towards acknowledging "religious citizenship" - or the state recognition of religious minorities.

Jokowi's decision to establish the university

On 13 April 2022, the governor of Bangka-Belitung (Babel) province, Erzaldi Rosman Djohan, announced that President Joko Widodo had selected the province as the centre for developing Confucian education due to its reputation for enjoying "highest degree of religious harmony in Indonesia". He also revealed that, prior to Lunar New Year 2022, he and the leadership of the Matakin had met the president who expressed his hope that an International State University of Confucianism (Perguruan Tinggi Negeri Internasional Agama Khonghucu, abbreviated as PTN Khonghucu) should be established by 2023.

It was reported that the government has allocated two plots of land for this purpose. Once established, this would be the only Confucian religion university in the world, and would attract global attention. The initiative to establish such a university shows that the Indonesian government is moving towards acknowledging "religious citizenship" - or the state recognition of religious minorities.

The establishment of this state-funded international university of Confucianism had in fact been decided in 2019. However, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the government could only offer a plot of land of 2.9 hectares to the Bangka-Belitung government in April 2022 for the university campus. According to local officials, the government has also prepared the budget for foundational works to begin in 2023.

This decision was opposed by the local Aliansi Ulama Islam (Islamic Ulama Alliance, AUI) of the Bangka-Belitung province, coordinated by Firman Saladin. On 31 May 2022, they went to the provincial parliament to lodge their dissatisfaction and threatened to launch a movement mobilising Muslim followers if the central government did not accept their demand.

Opposition and support for PTN Khonghucu

According to various reports, the objection of the ulama against the building of the PTN Khonghucu was based on the following arguments: Bangka-Belitung province comprises of a Muslim majority population. If PTN Khonghucu were to be built, students from China and other foreign countries would come to the province to study, which would offer an opportunity for Chinese students to migrate to Indonesia and affect the relationship between Muslims and non-Muslims, which would sour the good relationship between the two communities.

The AUI suggested that such a university should instead be established in West Kalimantan where there is a large ethnic Chinese population. However, they failed to mention that Chinese Indonesians form the second largest group in the Bangka-Belitung province. Interestingly, AUI claimed that their rejection was not due to "hatred" but to their love "for religious harmony".

The Indonesian public has been divided on this issue. While some agree with the views of AUI, others support the establishment of PTN Khonghucu in Bangka-Belitung. Those who agree with AUI are mainly conservative and radical Muslims, while those who oppose AUI tend to be moderate Muslims, intellectuals, Chinese Indonesians, and social media personalities.

For instance, a social media influencer Ade Armando who has 1.8 million followers on his Cokro TV programme, maintained that Indonesia is a democratic country based on Pancasila and that Confucianism is one of the religions recognised by the government; thus, Confucianism deserves to be treated fairly. He emphasised that, since the central government has established an International Islamic University of Depok in West Java, establishing a PTN Khonghucu, which is also an international university, appears to be a natural and logical move. This would also enhance the status of Indonesia among the international academic community. Likewise, the influx of Chinese students to study at the PTN Khonghucu should be welcome and would benefit Indonesia both culturally and economically.

Addressing the argument that Chinese nationals would migrate to Bangka-Belitung province in large waves, Armando pointed out the absurdity of it. In Armando's view, anti-PTN Khonghucu sentiments are based on exclusivism and xenophobia, and these should not be encouraged. He urged the central government to not abandon the plan to establish the PTN Khonghucu just because of the opposition of a few Islamic clergymen.

Herza likened the Chinese community in Indonesia to a homo sacer - a person of the minority group whose political right is deprived by the religious and political elite of the majority group who collaborate to remove the political right of the minority group.

Perhaps the most interesting argument was put forward in an open letter written by Herza, a young lecturer in the Department of Sociology at the Bangka-Belitung University. Herza is an indigenous Muslim who graduated from the Bangka-Belitung University and received a master's degree from Waseda University in Japan. He presented an academic argument using the notion of "Homo Sacer" as argued by Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben.

In the letter, Herza likened the Chinese community in Indonesia to a homo sacer - a person of the minority group whose political right is deprived by the religious and political elite of the majority group who collaborate to remove the political right of the minority group. Herza criticised the AUI, alluding that their actions resemble those of the elite described by Agamben.

Herza also highlighted that in the Bangka-Belitung province where the Muslim population form the majority, there is more than one state-run Islamic university and the Muslims there can enjoy the freedom to express, perform and practice their religion. However, the Chinese, who form the second largest population in the province, do not have a single Confucian university. Thus, they do not have the opportunity to learn about their religion in depth and as a result, they do not have sufficient knowledge about their own religion.

Will the PTN Khonghucu be eventually established? It appears that the realisation of this plan is contingent upon Joko Widodo being in power.

Herza argued that the freedom to enjoy life in accordance with one's religion is the political right of any citizen in a democratic country, thus a Confucianist should be allowed to receive religious education on Confucianism. He further posited that "the Chinese in Bangka-Belitung are not new migrants. They have been in these areas since the 18th century for many generations."

Nevertheless, the nature of the proposed Confucian university is unclear: will it merely teach Confucius philosophy and Chinese religious thought, or also secular subjects? From official statements, it can be assumed that the government leans towards the former. If this turns out to be the case, the university would be very specialised and unique - which forms the basis of the opposition of the AUI. However, even if the proposed university offers secular subjects, it is doubtful that the response of the AUI would have been any different.

Will the PTN Khonghucu be eventually established? It appears that the realisation of this plan is contingent upon Joko Widodo being in power. In other words, the university should be built before Joko Widodo steps down. If not, should a conservative Muslim politician be elected as the new president, it is unlikely that this university will be built anytime in the near future.

This article was first published by ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute as ISEAS Perspective 2022/100 "Can an International State University of Confucianism be Established in Indonesia?".