Will China abandon its 'no first use' nuclear policy?

Li Nan notes the seeming contradiction of China expanding its nuclear force while vowing not to fight a nuclear war. He explains that China seeks to ensure that it has nuclear counterattack capabilities that can survive the first nuclear attack and launch retaliatory strikes. At the moment, its "no first use" policy is intact, but the debate around it suggests that China's nuclear strategists have begun to explore the possibility of limited nuclear war that can be winnable against enemy targets.

China's strategic missile force was recently renamed the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF), implying an expansion. In January 2022, China joined the other four nuclear powers in affirming that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought. Examining the evolution of China's nuclear strategy may help understand the seeming contradiction between China expanding its nuclear force while vowing not to fight a nuclear war.

'Check and stop nuclear blackmail'

A critical driver for China to develop nuclear weapons was to "check and stop nuclear blackmail" (遏止核讹诈), a concept that defined China's nuclear strategy during the 1960s and 70s following its successful nuclear test in 1964. It is based on the premise that a country must possess nuclear weapons to prevent countries with nuclear weapons from blackmailing it.

Since this strategy has no clear requirements for the quantity and quality of nuclear weapons due to technological and financial constraints, it could only meet the minimal goal of symbolic possession to prevent blackmail. This crude strategy may also account for Beijing's lack of strategic communications with the outside world regarding its nuclear weapons, which was construed as a strategy of total ambiguity.

'Effective counter-nuclear attack deterrence'

As China has developed credible second-strike nuclear capabilities since the 1980s, the notion of effective counter-nuclear attack deterrence (有效反核威慑) has been adopted as China's nuclear strategy. This strategy requires China to develop nuclear counterattack capabilities that can survive the first nuclear attack and launch retaliatory strikes.

These nuclear counterattack capabilities can be limited but must be effective, and should be capable of being launched on command if an enemy attack is detected, a condition similar to the Western notion of launch-on-warning. Such a requirement implies that space surveillance capabilities need to be enhanced to provide sufficient early warning.

This strategy also requires China's nuclear force to acquire survival and protection capabilities so that sufficient capabilities can survive the rival's first nuclear attack. This force must also possess effective capabilities that can penetrate the rival's missile defence systems.

This strategy's requirements may account for China's recent efforts to acquire missile early warning technologies; develop its own strategic missile defence systems; deploy solid-fuel, road and rail-mobile strategic nuclear missiles; develop multiple independent reentry vehicle-capable inter-continental ballistic missiles; deploy quieter strategic nuclear submarines; reveal its first nuclear-capable refuelable bomber and a nuclear-capable air-launched ballistic missile; build nearly 300 strategic missile silos in Western China; and test nuclear-capable hypersonic missiles.

As China modernises its nuclear force, a debate has emerged on whether to change China's nuclear strategy, including abandoning its 'no first use (NFU)' policy.

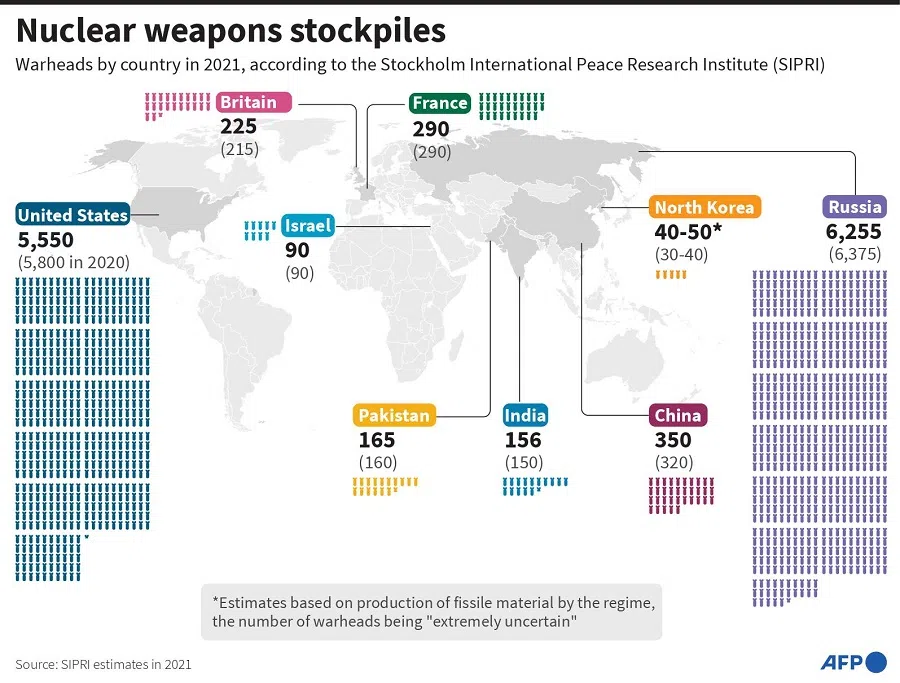

A Pentagon report predicts that China may have up to 700 deliverable nuclear warheads by 2027. It says: "The PRC likely intends to have at least 1,000 warheads by 2030, exceeding the pace and size the Department of Defense projected in 2020."

Finally, China's military analysts believe that effective strategic communications with the outside world are indispensable. These communications include demonstrating China's credible quantity and quality of nuclear capabilities and its will and resolve to use them, and letting the potential rival be absolutely convinced of China's willingness to use nuclear weapons.

This belief may account for the Chinese media coverage of military parades involving China's strategic nuclear capabilities, and publicity of China's early warning capabilities and its strategic missile defence systems.

Debating 'no first use' policy

As China modernises its nuclear force, a debate has emerged on whether to change China's nuclear strategy, including abandoning its 'no first use (NFU)' policy. NFU of nuclear weapons is the cornerstone of China's nuclear policy, which is consistent with China's second strike-based strategy of effective counter-nuclear attack deterrence. There has been discontent with this policy among China's military planners, as reflected in several critical views of NFU.

One such view is that NFU imposes limits on employing PLARF in crisis. The highly centralised decision-making due to NFU may reduce China's response flexibility. Some also believe that NFU lowers the credibility of China's small nuclear force, but abandoning NFU may enhance the credibility of China's nuclear deterrence. They are impressed by Russia's abandonment of NFU policy to compensate for its inferiority in conventional military capabilities. Abandoning NFU, they argue, is the most cost-effective way to shift scarce resources from defending China's strategic targets to developing offensive capabilities to realise China's primary strategic objectives.

Some also argue that China should abandon NFU and launch a first nuclear strike in several critically threatening scenarios. One such scenario is the inability of the PLA conventional force to defend China against a large-scale foreign invasion. Another refers to situations where PLA operational objectives face an "enormous threat" of a large-scale foreign military intervention in a war of safeguarding national unity, implying a Taiwan conflict scenario. Moreover, war escalation indicating the rival's intention to cross the nuclear threshold justifies China's first use of nuclear weapons.

The rival's conventional attack on Chinese targets of life-and-death value like the Three Gorges Dam also warrants China's first use of nuclear weapons since this attack may cause destruction comparable to or larger than that of a nuclear attack. So does the rival's conventional attack against China's nuclear weapons and bases, which "poses an enormous threat to our nuclear force".

Supporters of NFU policy offer a number of rebuttals. They point out that the decision to employ nuclear weapons has always been highly centralised regardless of whether China adheres to NFU. They also note that Russia's abandonment of NFU in 1993 did not deter NATO from its eastward expansion nor did it stop the US from waging a war in Kosovo. An additional concern is that if the weaker side abandons NFU when the gap in nuclear capabilities is too large, it may trigger a pre-emptive nuclear strike against it by a superior rival.

They further argue that a large-scale foreign invasion of China is unlikely. Due to drastic increase in the destructiveness of modern warfare, major powers prefer to pursue limited objectives with limited wars. The extraordinary difficulties that superpowers encountered in conquering countries such as Vietnam and Afghanistan also demonstrate the futility of such an invasion. Since China is a major power armed with nuclear weapons, the cost of a total invasion of China is unacceptably high.

Furthermore, since China regards Taiwan as its core interest, its resolve for reunification should dwarf US incentive to intervene. China has also stepped up the buildup of its conventional military capabilities to deter Taiwan independence and US intervention. On the other hand, abandoning NFU may have little impact on the US decision to intervene because it has "absolute nuclear superiority" over China. Some also point out that it is immensely difficult to determine whether a rival has crossed the nuclear threshold that may justify a preemptive nuclear strike.

On conventional attacks on China's life-and-death value targets and nuclear weapons facilities, NFU supporters argue that recent local wars demonstrate that military attacks meant to cause civilian casualties and economic losses are rare; these attacks are mainly intended for military targets to realise military objectives. China also can deter these attacks since it has long-range, conventional precision-guided strike capabilities. These capabilities can be employed to retaliate in kind, to strike both the homeland and overseas targets of the rival. Foreign conventional attacks against these Chinese targets thus are highly unlikely.

On the other hand, the debate on NFU suggests that China's nuclear strategists have begun to explore the possibility of limited nuclear war and developing tactical nuclear weapons, which is associated with the premise that such a war can accomplish political objectives and thus is winnable.

The prospect of limited nuclear war

NFU supporters have clearly won the debate since NFU has remained China's nuclear policy. Meanwhile, China may adopt a more assertive nuclear force posture, including increasing its strategic nuclear missiles, deploying a triad of land, sea and air-based nuclear deterrent, mating its nuclear warheads with rockets in peacetime, and adopting a launch-on-warning stance. These changes, however, are still confined to developing China's second-strike nuclear capabilities for deterrence, which is based on the premise that a nuclear war causes mutually assured destruction (MAD) and thus is unwinnable.

On the other hand, the debate on NFU suggests that China's nuclear strategists have begun to explore the possibility of limited nuclear war and developing tactical nuclear weapons, which is associated with the premise that such a war can accomplish political objectives and thus is winnable. In their internal discussions, these strategists explicitly state that "to effectively deter the conventional invasion or armed intervention by a nuclear rival, it is necessary to possess both precision-based tactical nuclear strike and destruction-based strategic nuclear strike capabilities... The former are used to target the rival's forward deployed operational forces and the latter serve to destroy its military capabilities deployed in-depth."

Rather than the counter-value targets associated with MAD, this statement suggests that the rival's military forces should be targeted in a nuclear war. This implies that such a war can be controlled and limited and thus can be fought and won. It also implies that more sophisticated tactical nuclear weapons and highly coordinated command and control can be deployed to compete for dominance at different levels of escalation in times of crisis and war.

While it is reassuring that NFU supporters have won the debate and there is little evidence that China has deployed tactical nuclear weapons, any change regarding China's nuclear force posture may need to be carefully identified and analysed.

An initial version of this article was first published as an EAI Background Brief.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)