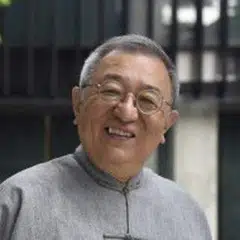

Cheng Pei-kai

Cultural Historian

After graduating from National Taiwan University in Western Literature, Professor Pei-kai Cheng obtained his PhD in Chinese Cultural History from Yale University in 1980 and was a John King Fairbank post-doctoral fellow at Harvard University in 1981. He taught at State University of New York at Albany, Yale University and Pace University in New York for 20 years. He later founded the Chinese Civilization Center at City University of Hong Kong in 1998, serving as its director until his retirement in 2013. He has been a visiting professor at Zhejiang University, Peking University and University Professor at Fengjia University in Taiwan. Awarded the Medal of Honor by the Hong Kong government in 2016, he is now chairman of the Hong Kong Intangible Cultural Heritage Consultation Committee. He has published more than 30 books, and edited various series of collections on Chinese history and culture. His research interests cover a wide spectrum of academic subjects on Chinese culture, such as late Ming culture and Tang Xianzu, transcultural aesthetics, tea culture, Chinese export porcelain, and English translation of Chinese classics. He is also the founder of Chinese Culture Quarterly and has been its editor-in-chief since 1986.