China's all-out effort to wipe out scam syndicate families in northern Myanmar

It seems that scam operators, not least the "four big families" of northern Myanmar or Kokang, are being put on notice in Northern Myanmar. Skirmishes between the Brotherhood Alliance armed forces and the junta are helping to ferret out these organisations. Given that Kokang borders China, the animosity between the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and the junta government will test how China strikes a balance between them.

Amid bounties offered by the Chinese government and aggressive offensives by northern Myanmar allied militia, it seems the game is up for scam syndicates in northern Myanmar.

On 12 November, China's Ministry of Public Security offered bounties on Ming Xuechang and other ringleaders of telecom scam syndicates in the Kokang Self-administered Zone (SAZ) of northern Myanmar. That same night, videos featuring Wei Qingtao and other core members of the "four big families" in northern Myanmar expressing remorse made the rounds.

Wei was arrested by the Chinese police. Facing the camera, he told his family members plainly: "This time round, the Chinese government will not let up until it has eliminated telecom scams." He added that the current outbreak of violence in Myanmar can lead to severe casualties at any time, and urged his family members not to harbour any illusions, but to seize the last chance to open up scam hubs and hand all Chinese nationals back to China.

Wei ended off by saying, "If any Chinese national is hurt or dies on the premises, we will not be able to take the consequences. The Chinese government will definitely make us pay in blood."

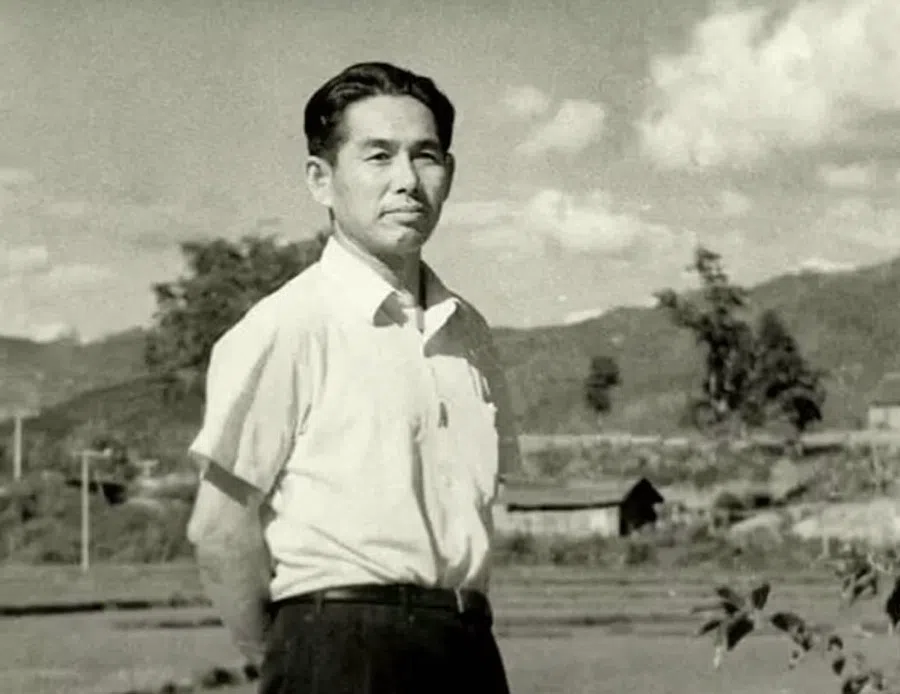

The "four big families" of northern Myanmar or Kokang are headed by Bai Suocheng, Wei Chaoren, Liu Guoxi and Liu Zhengxiang...

The 'four big families' and the rising Ming family of northern Myanmar

On the morning of 14 November, after the videos were circulated, online searches related to northern Myanmar were among the top searches on Weibo: "The 'four big families' of northern Myanmar", "Henry Group", "Who is funding the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army", and "Crouching Tiger Villa" .

The "four big families" of northern Myanmar or Kokang are headed by Bai Suocheng, Wei Chaoren, Liu Guoxi and Liu Zhengxiang, all local Kokang people. They control the mining business, commerce, and real estate business in Laukkai, the capital of the Kokang SAZ in northern Myanmar. Behind the scenes, the families are also involved in illicit activities such as telecom scams and gambling. The man in the video, Wei Qingtao, is the second son of Wei Chaoren.

Wei Qingtao, Liu Zhengqi (younger brother of Liu Zhengxiang) and Bi Huijun (son-in-law of Ming Xuechang) were reportedly arrested in China back in October, and are currently assisting the Chinese police with investigations. Liu and Bi apparently hold Chinese identity cards and are registered as Yunnan residents. While Wei and Liu are both key members of the "four big families", the Ming family is a new force on the rise.

Things developed quickly thereafter. On 15 November, it was reported that the family members of Bai Suocheng were killed while they were flying back to China to surrender - the helicopter they were in was hit and crashed by the Myanmar militia.

The Ming family clout was also much diminished when Ming Xuechang reportedly shot himself while trying to escape a raid on 15 November, and later succumbed to his injuries. Xinhua also reported that police in Myanmar arrested Ming's son Ming Guoping, daughter Ming Julan and granddaughter Ming Zhenzhen and handed them over to the Chinese police on 16 November.

Kokang is in the Shan State of northern Myanmar, bordering Yunnan. It is mostly populated by ethnic Chinese, with a high degree of autonomy.

Bai Suocheng was the first chairman of the Kokang SAZ. His family runs the Baisheng Corporation which is involved in hospitality, food and beverage, and real estate development. The Wei family runs the Henry Group. Liu Guoxi's family is involved in mining, while Liu Zhengxiang started out in drug trafficking before founding the Fulaili Group (福来利集团). The Ming family has close links with the "four big families". Its Crouching Tiger Villa is the largest telecom scam compound in Kokang.

Allied militia to clear telecom scams?

This year, China and Southeast Asian countries have launched numerous joint operations, ramping up efforts to clamp down on telecom fraud. Chinese authorities said on 21 November that Myanmar authorities have handed over 31,000 telecom fraud suspects to China since law enforcement officers from both countries launched a crackdown on online scams in September.

China's recent major breakthrough against telecom scams is also related to the latest armed conflict in northern Myanmar.

On 27 October, the Brotherhood Alliance comprising the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), the Ta'ang National Liberation Army, and the Arakan Army attacked government armed forces.

For long periods in the previous century, ethnic minority militias in northern Myanmar tussled with the junta government. After 1988, these militias successively signed ceasefire agreements with the central government, but retained a high degree of autonomy and continued to seek opportunities to expand their territories.

On the day of the attack, the MNDAA released a statement that they were taking action to root out telecom fraud operators, premises, and protectors in Myanmar, including in the China-Myanmar border region.

Over the past few weeks, the MNDAA has attacked swiftly and fiercely under the banner of fighting scams. According to pro-MNDAA blog Kokang123 ("果敢资讯网"), as of 13 November, the MNDAA has taken over at least 170 bases that were previously controlled by government forces.

A commentary in the Southern People Weekly (《南方人物周刊》) noted that the government military bases around Kokang capital Laukkai have been cleared, and once the MNDAA seizes back control of Laukkai, the battle is as good as over.

... most Chinese netizens are cheering the MNDAA, saying "as long as there is revenge by wiping out telecom scams" and "whatever it is, fighting with us against the scam syndicates is good".

The clashes are now spreading to Myanmar's western and eastern borders in what analysts say is the biggest military challenge to the junta since it seized power in 2021.

The Chinese authorities are currently advocating for peace; when the armed conflict broke out on 27 October, its Ministry of Foreign Affairs immediately called for a ceasefire to ensure the security and stability of the China-Myanmar border region.

Chinese Minister for Public Security, Wang Xiaohong, and Nong Rong, an assistant minister for foreign affairs, made separate visits to Myanmar. On 31 October, Wang met Min Aung Hlaing, leader of Myanmar's junta government, for talks on peace and order at their border.

However, most Chinese netizens are cheering the MNDAA, saying "as long as there is revenge by wiping out telecom scams" and "whatever it is, fighting with us against the scam syndicates is good".

An article on the BBC's Chinese-language website which was written by its Bangkok outlet said that China was a check on conflicts in northern Myanmar, but this time it did not prevent military action at its border, possibly because the Chinese government was disappointed by the junta government's lack of action against the proliferation of telecom scam operations, while the militias claimed that one of their aims is to raid the scam hubs.

For the MNDAA, it needs to reclaim Kokang as its stronghold. For the "four big families", the businesses in Kokang - legitimate and otherwise - built by two generations will not be surrendered easily.

Historical grudges

But while the MNDAA claims that it is going after the telecom scam syndicates, its grudge with the "four big families" goes back to before the telecom scams.

The MNDAA was established in 1989 by Peng Jiasheng (Pheung Kya-shin), known as "the King of Kokang". Peng was of Chinese descent and was born near Kokang. In 2009, Bai Xuoqian (Bai Suocheng), who was Peng's deputy then, joined with the other three "big families" to stage a coup, ousting Peng from Kokang.

In 2014, Peng led more than 1,000 fighters in an unsuccessful counterattack to reclaim Kokang. After Peng died of an illness in 2022, the MNDAA leadership went to his eldest son, Peng Deren, but the MNDAA's lack of a stronghold prevented it from growing.

While Kokang is just 2,000 square kilometres in size with a population of only 140,000, it is a target of contention for various parties.

For the MNDAA, it needs to reclaim Kokang as its stronghold. For the "four big families", the businesses in Kokang - legitimate and otherwise - built by two generations will not be surrendered easily. For the junta government, Kokang is the first special zone it needs to safeguard in Shan State, and the knock-on effects of losing it would be unimaginable.

After winning back Laukkai

The fighting in Kokang also affects China. While it would be good for China if the MNDAA regains Laukkai and eradicates the scam syndicates, China has far more to consider than that.

First, it needs to think about how to deal with the scammers, with their complex network. Besides the ringleaders, most are frontline scammers involved in telecom frauds. Some are trafficked into Myanmar, while some are lured there by the good pay; convicting and punishing them is a problem for China.

Given that Kokang borders China, the animosity between the MNDAA and the junta government will test how China strikes a balance between them.

On 13 November, the Chinese Ministry of Public Security released a draft document for public feedback on joint punitive measures for telecom scams and related crimes (《电信网络诈骗及其关联违法犯罪联合惩戒办法(征求意见稿)》).

Another question for the Chinese government is the development of China-Myanmar relations if the MNDAA regains control of Kokang. Given that Kokang borders China, the animosity between the MNDAA and the junta government will test how China strikes a balance between them.

On 13 November, an article by the Le Monde correspondent in Southeast Asia said the incursion by the MNDAA is an indirect consequence of China's anti-scam campaign. The article also mentioned that this marked a reset of the relationship between China and the junta government, and questioned China's role in the Kokang conflict.

A family like the Weis has already established new scam hubs in Thailand and Cambodia, so cutting off one branch does not mean getting to the root.

Furthermore, Myanmar is part of China's Belt and Road Initiative. The China-Myanmar economic corridor spans nearly 1,700 kilometres, and in particular, the gas and oil pipelines that connect both countries affects China's energy security. Turmoil in Myanmar will inevitably pose a challenge to China's projects in the country.

Telecom fraud syndicates are widespread in Southeast Asia. Even if they are wiped out in Myanmar, others remain in Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and the Philippines. A family like the Weis has already established new scam hubs in Thailand and Cambodia, so cutting off one branch does not mean getting to the root.

However, looking at official figures, of the 464,000 telecom scam cases solved by the Chinese public security authorities in 2022, some 60% originated from northern Myanmar, so busting the families is likely to stop the upward trend of telecom scams. But the evils of human nature are difficult to uproot, and for China and the rest of the world, the war against scam syndicates will be long and unceasing.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "缅北电诈家族末日将至?".