[Photo story] China-US relations in the late 19th century: Is history repeating itself?

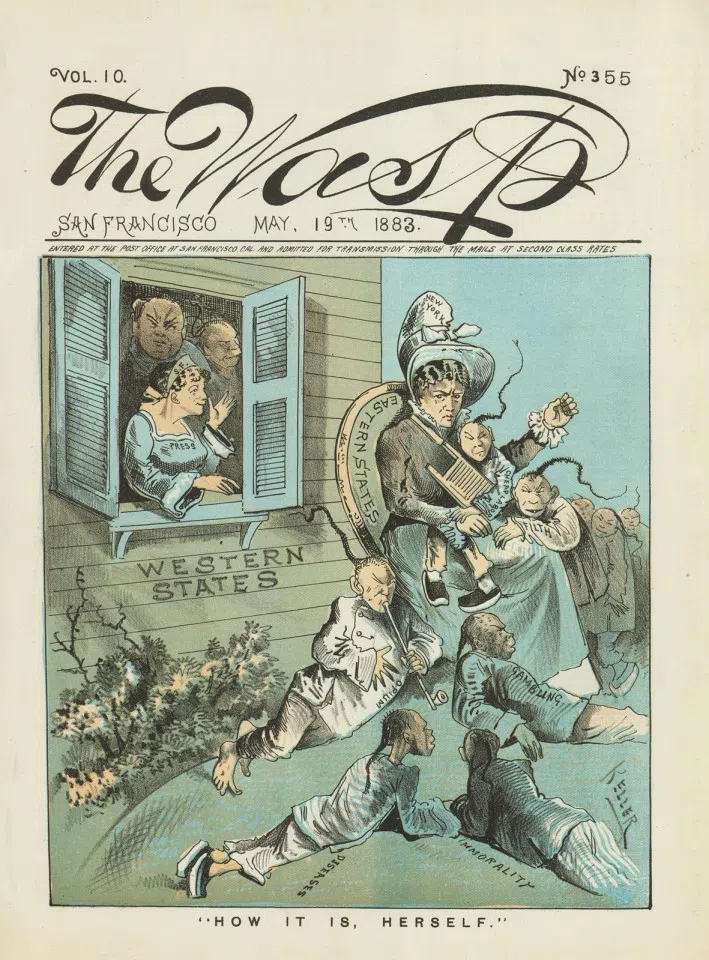

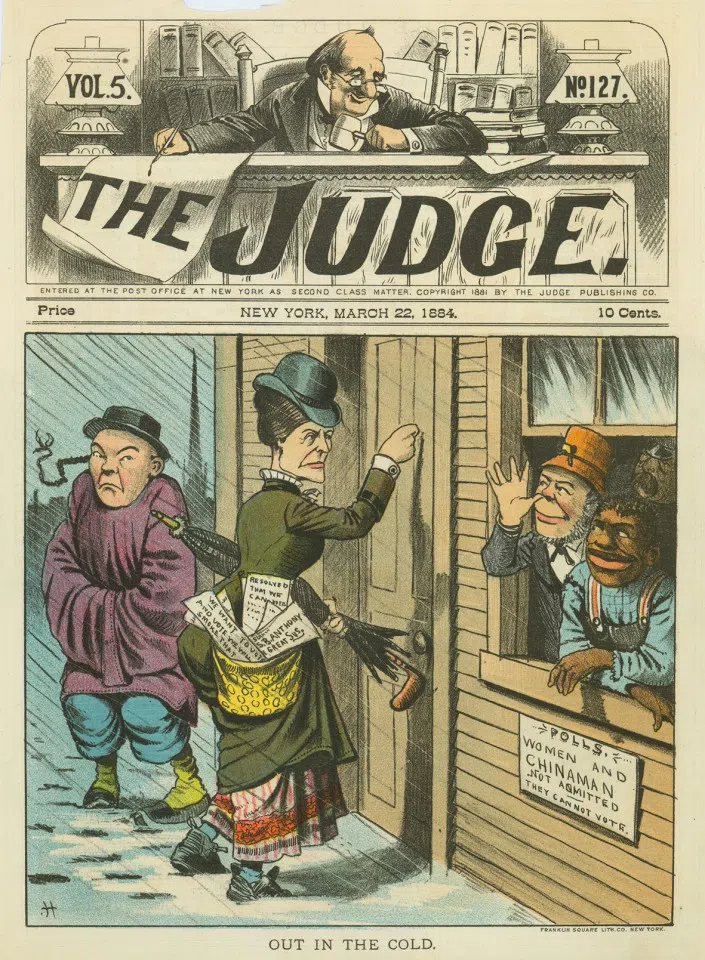

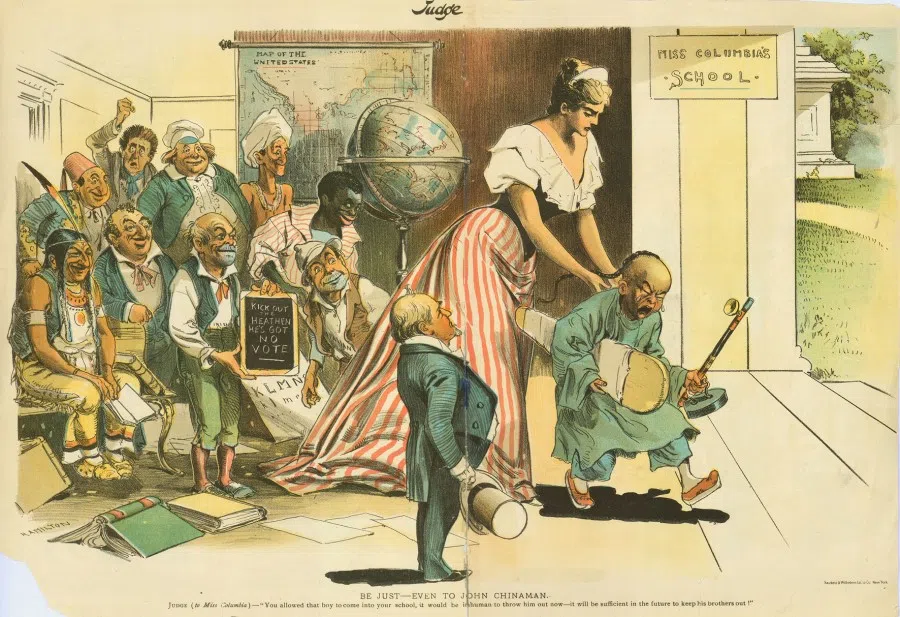

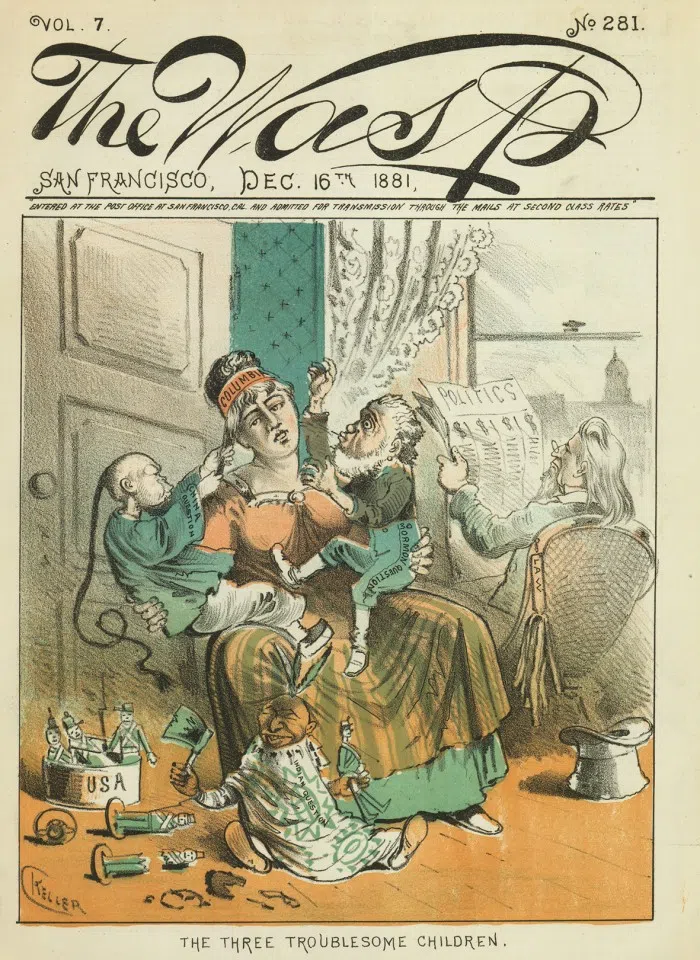

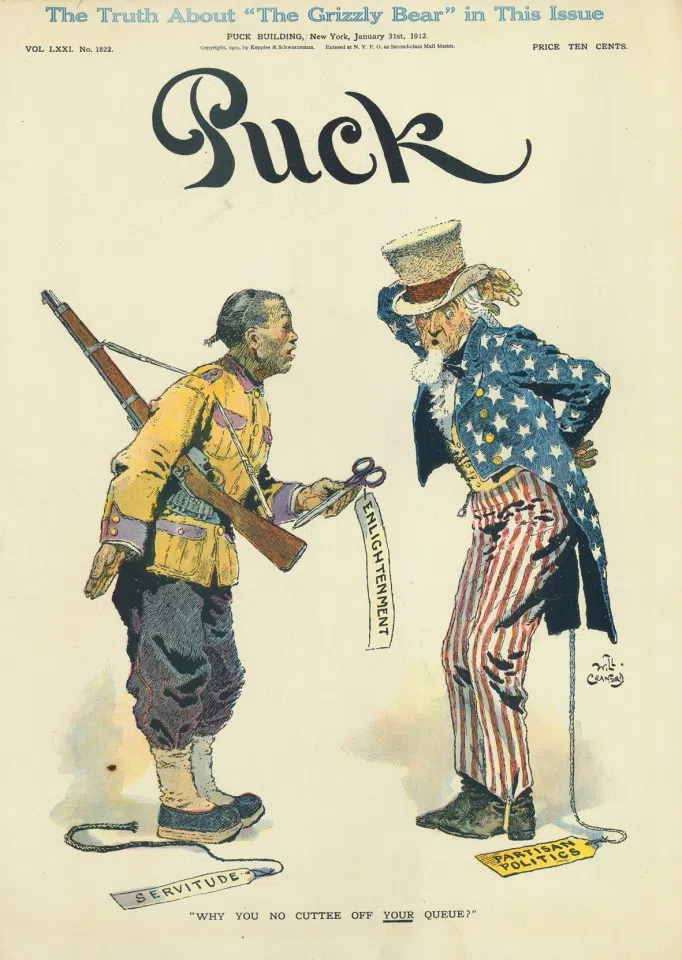

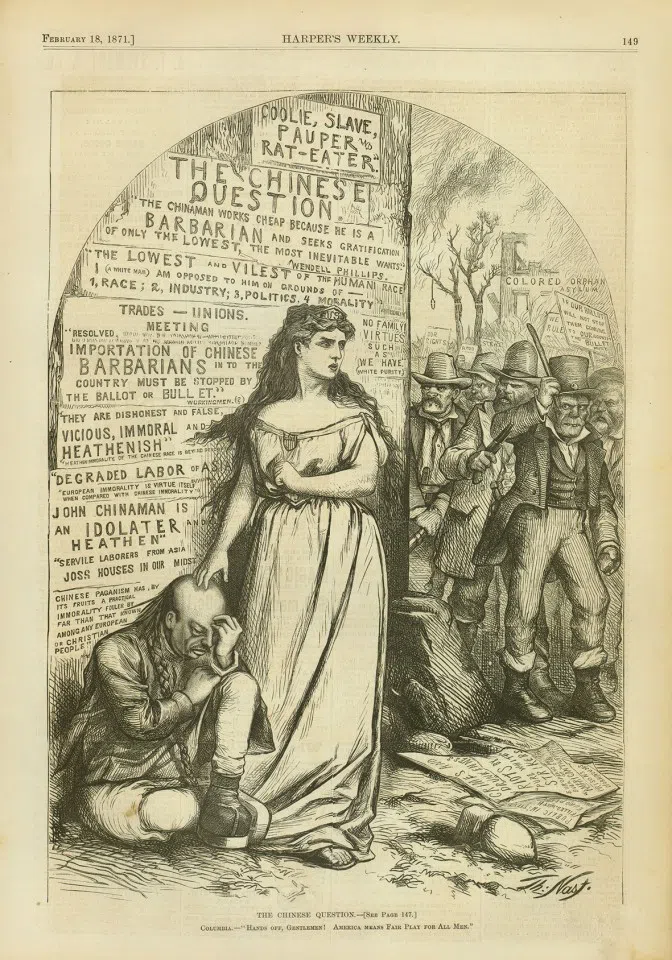

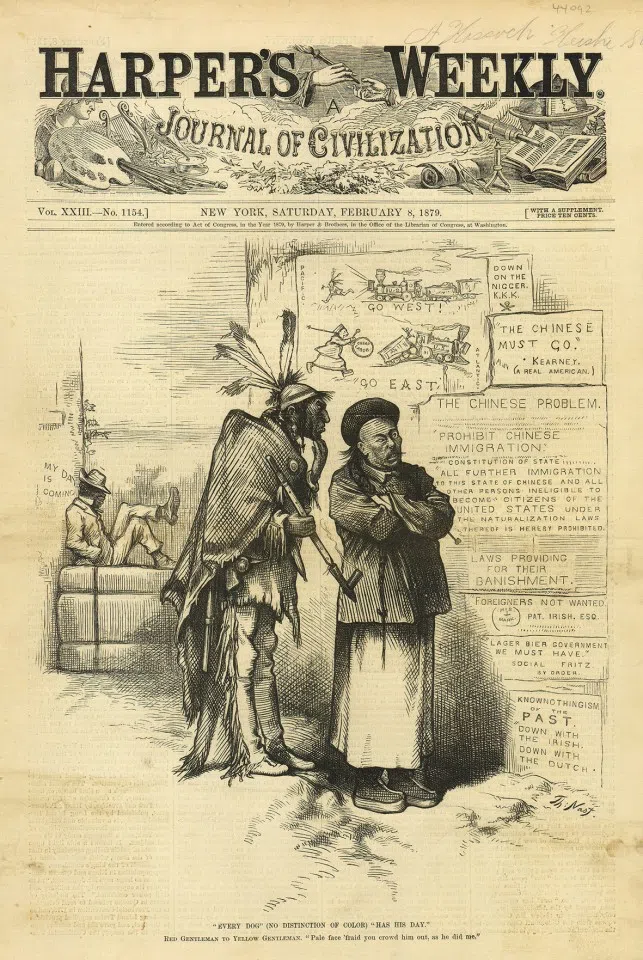

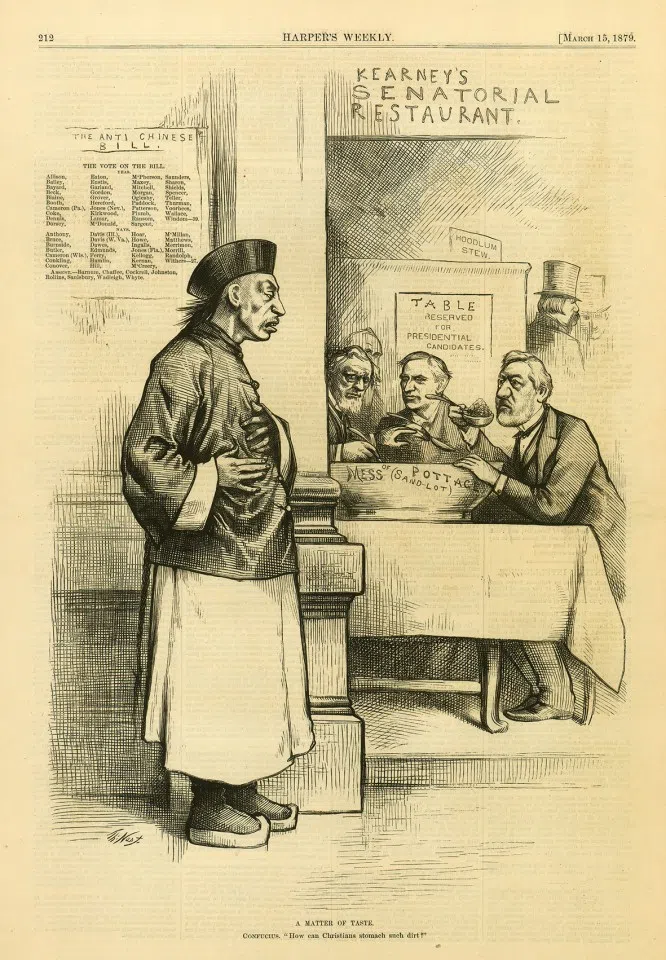

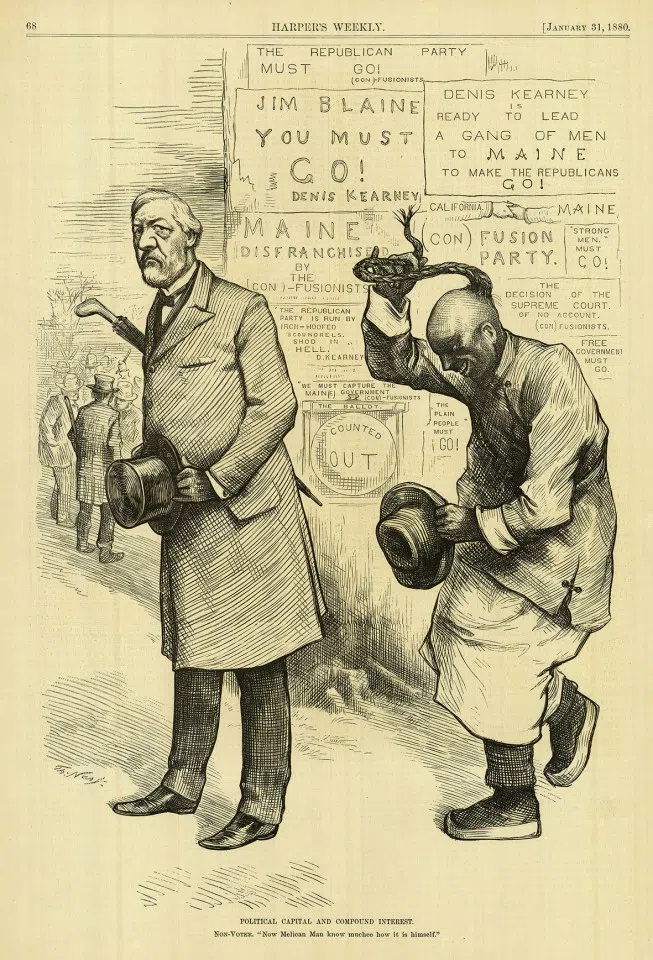

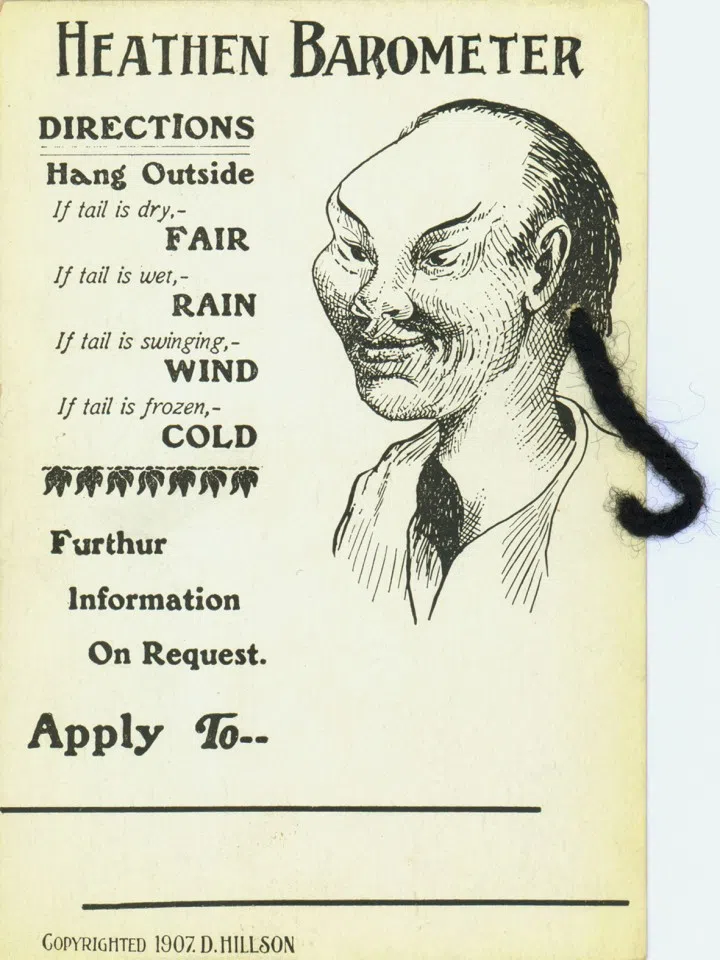

Were China-US relations always as they are now? Or was there something that changed the situation? Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao presents powerful images from US magazines in the late 19th century, which depict sinophobia in US society and difficulties in China-US relations more than a century ago. Are these images proof that history repeats itself?

(All images courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

Modern relations between China and the West arose in discord. As the West grew in industrial might, it sourced for materials from overseas markets. They came to China seeking to build relations, but it was not just commercial ships that arrived - there were also strong fleets to protect maritime trade interests.

Despite the advent of a new era, the ancient Chinese empire stubbornly held to its pride and viewed these visits in the traditional sense of relations between Chinese and "foreign barbarians". Opium trade issues led to the British opening China's doors with gunboats and to their reputation of forcing drugs to be sold to the Chinese. With the Second Opium War of 1860, the Western powers deployed envoys to the Chinese capital of Beijing and obtained land concessions in major cities. China bore the humiliation of paying huge amounts of war reparations and a loss of sovereignty.

Given the friendliness of the US, when China first sent students overseas to study, they chose to go to the US and not Britain, which was then the world's most powerful country.

US-China relationship's friendly beginnings

US-China relations came later, but started off friendlier than British-French relations. In 1868, China and the US signed the Burlingame Treaty. China had quite a good impression of the US because of this treaty, as she saw it as the first equal agreement that had been forged in recent diplomatic history.

The treaty stated that each side had a right and duty to appoint consuls, that US citizens could establish schools in China and vice versa, that people had an inalienable right to migrate, and that the US had no right and no intention to intervene in China's domestic administration. Given the friendliness of the US, when China first sent students overseas to study, they chose to go to the US and not Britain, which was then the world's most powerful country.

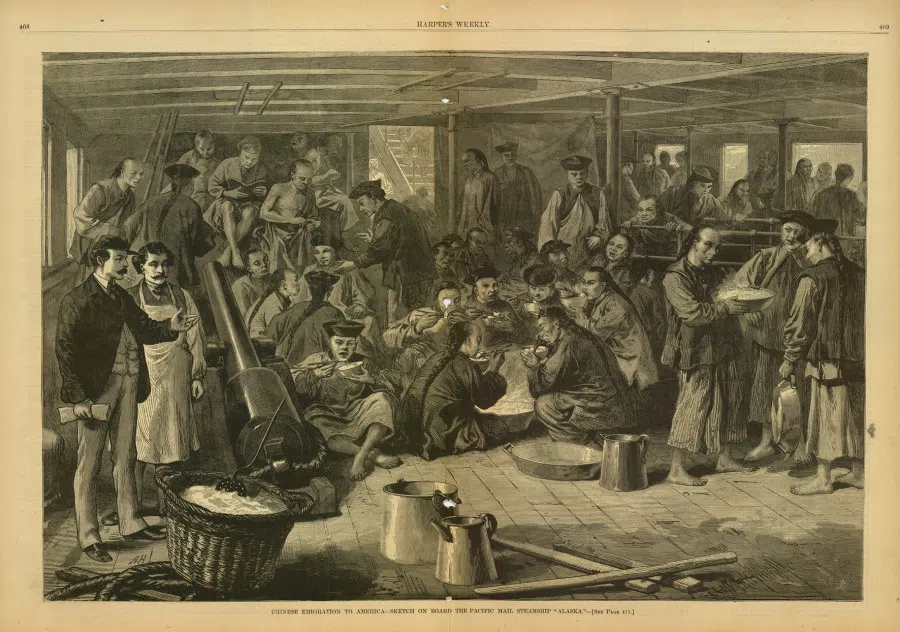

The treaty also provided a legal basis for Chinese labourers to migrate to the US. The California gold fever of 1848 drew many Chinese migrants, but the real wave of labourers came with the construction of the Pacific Railroad. The earliest Chinese labourers who came to open up the US West Coast were mostly from the coastal areas of Guangdong. Nearly nobody could afford the costly travel fees, and so a tightly organised guarantor system was born, usually headed by a broker from a particular clan. Those who wanted to make the journey had to sign a contract with the broker, who arranged the ship and costs.

But when the railway was opened, not one Chinese worker was invited, a frequently cited example of regrettable discrimination.

On reaching the US, the workers had to repay the fees with part of their salary or by working for a particular period of time. As most of these workers were illiterate and did not know about salary standards in the US, the contracts were usually unfair to the workers. In Cantonese, such trades were known as "selling piglets" (卖猪仔).

When the American Civil War ended in 1865, it was a time of peaceful development. Construction of the Pacific Railroad was accelerated. At its peak, there were 15,000 Chinese involved in construction. They worked all day and night and were prepared to live in harsh conditions, and showed more industry and grit than the Irish, who made up most of the white labourers. But when the railway was opened, not one Chinese worker was invited, a frequently cited example of regrettable discrimination.

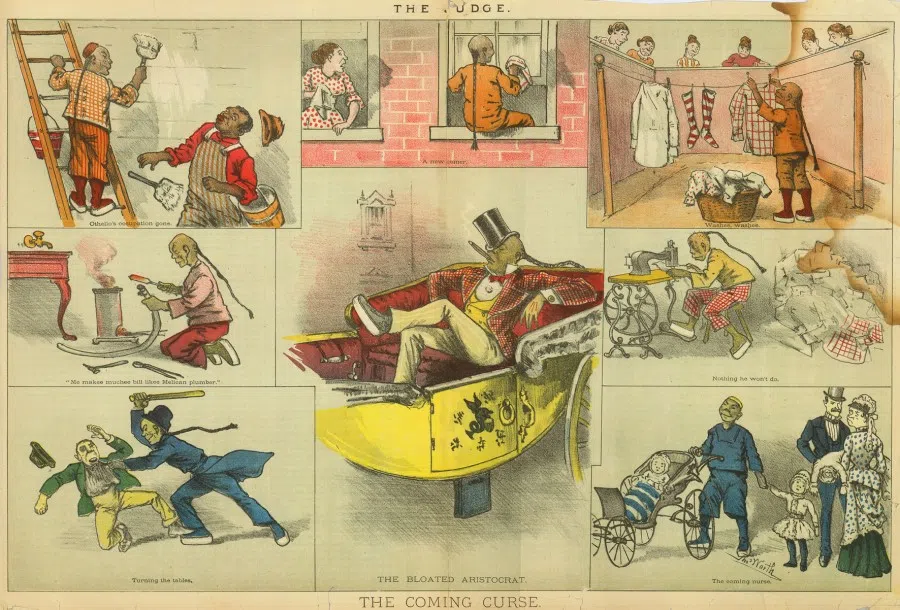

This strong competitiveness sparked anger and unhappiness among the low-level white workers, who violently attacked Chinese and put strong political pressure on senators.

This influx of Chinese sparked unexpected cultural conflict and friction between China and the US. The real problem was that after the railway went into operation in 1869, the Chinese migrant workers moved to the East and West Coasts to make their living. As China was still recovering from the Taiping Rebellion, most Chinese workers chose to stay in the US, working hard at various jobs in big cities for low wages. Their aim was to give the next generation a good education so that they could gradually move out of first-generation migrant poverty. This strong competitiveness sparked anger and unhappiness among the low-level white workers, who violently attacked Chinese and put strong political pressure on senators.

The Chinese Exclusion Act

In 1882, the US Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act which stopped Chinese workers from entering the US for the next 10 years, while imposing strict rules on the naturalisation of Chinese. This was the first time that the US implemented immigration restrictions targeted at a specific race that also effectively went against the spirit of the Burlingame Treaty. In 1892, Congress extended the Chinese Exclusion Act by another 10 years, and then indefinitely in 1902, which was equivalent to the US shutting the door on free migration of the Chinese.

To put it simply, the external environment for China-US relations was good, but friction happened mainly because US workers rejected the Chinese work culture.

The business community and ordinary people in China came up with policies to counter such discrimination against Chinese. The Shanghai Chamber of Commerce took the lead in calling for the authorities to change the harsh laws within two months or else the whole of China would boycott US goods. Business associations everywhere in China were quick to respond and call for the Chinese to come together in resistance through the newspapers.

The United States Asia Chamber of Commerce felt the anger of the Chinese people and was afraid that the US's considerable trade interests in China would be affected. It quickly wrote to President Theodore Roosevelt to ask for the Chinese Exclusion Act to be amended to allow free movement in and out of the US for Chinese non-labourers, to prevent a total boycott of US products, churches, and ships.

President Roosevelt realised the severity of the problem, but stuck to his "carrot and stick" diplomacy. He issued an executive order to allow Chinese non-labourers such as businessmen, students, tourists, and officials preferential treatment in freely moving in and out of the US, and announced that all officials who harassed or discriminated against Chinese would be removed and investigated. On the other hand, he exerted diplomatic pressure on China in asking the Qing court to clamp down on the boycott of US goods. It was not until 1943 when China and the US fought together against Japanese imperialism that the discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act was removed.

To put it simply, the external environment for China-US relations was good, but friction happened mainly because US workers rejected the Chinese work culture. This led to political hostility towards Chinese workers, which was extrapolated into China-US diplomatic friction. In some sense, the problem of domestic economic factors evolving into political and diplomatic issues is also recurring in today's China-US relations. These images from US magazines in the late 19th century show the sinophobia in US society and the difficulties in China-US relations in such a political climate.

. . . . . .

Notes:

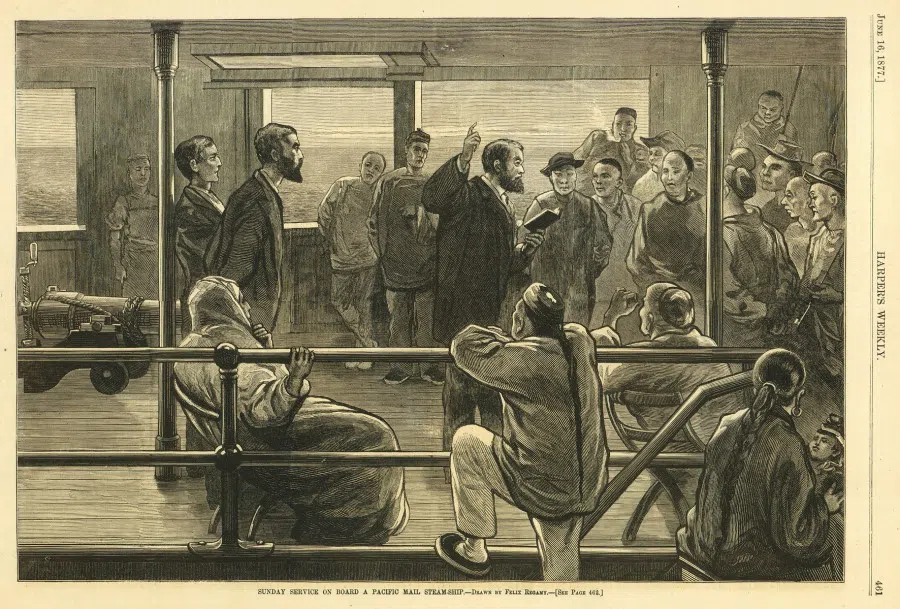

1. Chinese organisations always held a sense of mystique for Americans. The accompanying report sought to explore the Six Companies, a Chinese broking association which held a monopoly on the business in America. With significant initial demand in the US for Chinese workers, recruiting workers and arranging ships was expensive, and naturally led to the formation of a multinational business network. Clan organisations based on families, relations, and hometowns were a good way to start, and many migrants to the US came from the same village or family, especially when travelling in groups.

When they arrived, they continued to be managed - or controlled - by the same broker, to ensure the contract was fulfilled and the fees repaid. Such an organisation went beyond the white person's understanding of a "company", encompassing complicated employer-employee relations, kinship, and traditional Chinese culture. With external conditions getting worse for Chinese, these clan organisations became more united in opposition to policy discrimination and violence.

The Six Companies brought together other clans and established the US Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (全美中华公所), the first legal "local government" in the Chinese community. The association was in charge of managing business operations, mediating disputes, and protecting the rights of the community, as well as representing the Chinese in external discussions. The head of the association was as good as an unofficial mayor of a Chinese city, and even the Chinese government recognised the power of the association.

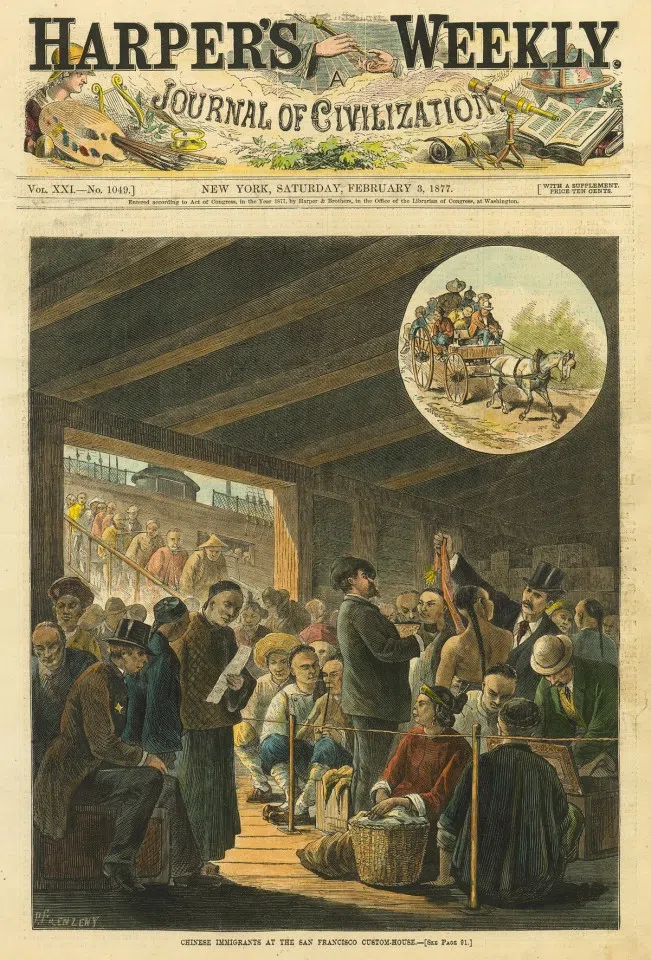

2. The customs officials were mostly after contraband such as opium, silk, and ivory products. Opium was not yet banned from import to the US, but had to be taxed, and the arrival of the Chinese did add to the proliferation of opium dens, while directly encouraging the spread of opium. According to another Harper's Weekly report, a conservative estimate had it that about 70,000 pounds of opium was imported each year in the 1870s, and an estimated 4,000 Americans and 10,000 Chinese who smoked it, with San Francisco having the most serious problem. Another study noted that in 1885, over 200,000 pounds of opium were smuggled into the US by the Chinese alone, nearly three times the figure in Harper's Weekly - perhaps Harper's Weekly only calculated based on customs figures from the US Treasury and left out black market smuggling, seriously underestimating the number of opium users in America.

Ironically, in the early 19th century, American merchants were once China's largest opium importers. Opium imports to the US alone made up half of the volume to all other countries, but British merchants subsequently overtook China's position with low-cost Indian opium. By the mid-19th century, the Qing government had repeatedly banned opium imports, but some American businessmen were still smuggling it under the US flag. British envoy Henry Pottinger recalled: "The main business of opium trade in China involves American-made ships, American captain and crew, and even open smuggling with the US flag flying on board."