[Photo story] How Korea and China fought together against Japanese colonial control

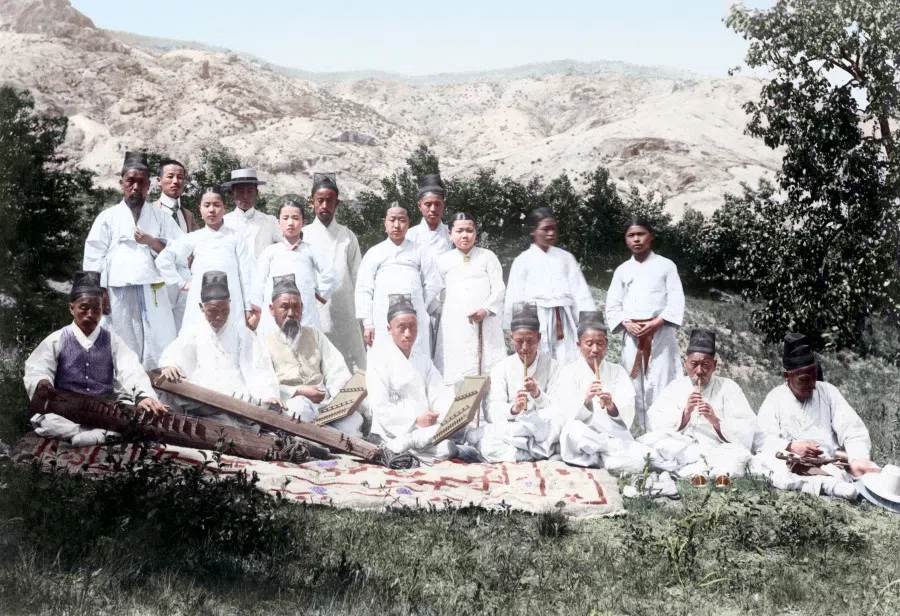

The Korean independence movement actually began soon after the Russo-Japanese war, when Korea and China fought together against Japanese colonial control. For some 30 years, Korean activists carried out resistance movements against the ruling Japanese government, until the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was established with Kim Gu as one of its most important leaders. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao gives a glimpse into the period.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

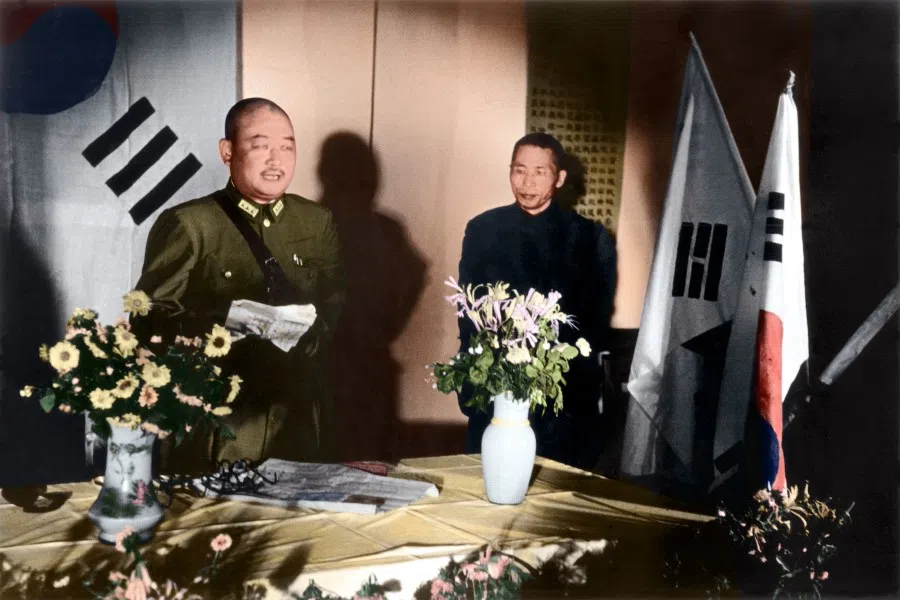

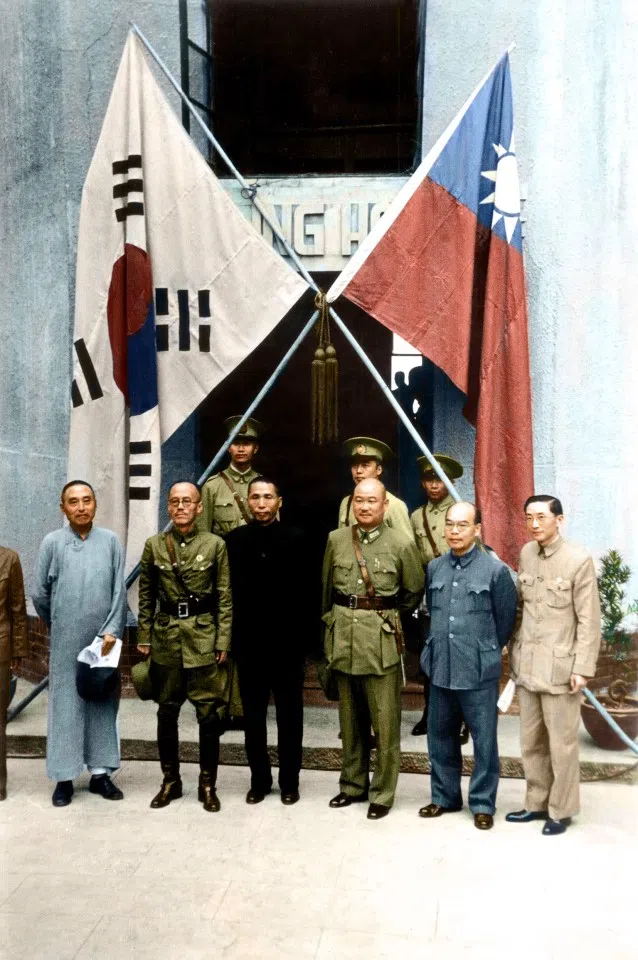

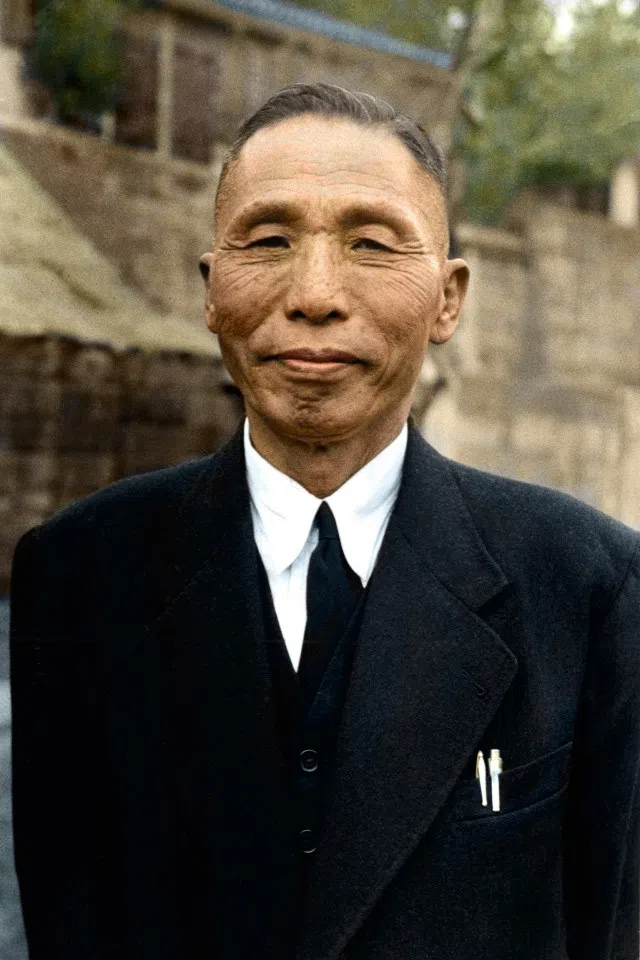

In November 1945, Kim Gu, president of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (Korean Provisional Government or KPG) flew back to Korea. But before that, he had a photo taken in Chongqing. This was where he and his delegation were seen off by Nationalist government chairman Chiang Kai-shek and senior leaders, marking the official end of their 26 years of exile in China and excitement at building a new Korea.

Kim Gu was born in 1876 to a poor farming family in Haeju, South Hwanghae province. From his youth, he was strongly nationalistic, and as an adult, he was involved in the armed resistance against the Japanese, and was arrested more than once by the Japanese government.

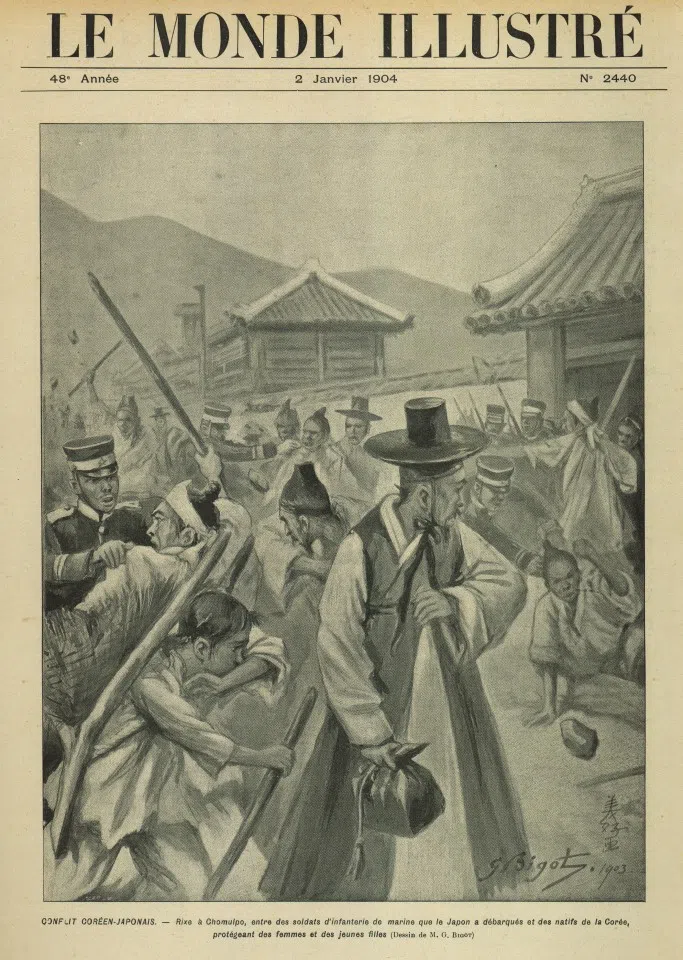

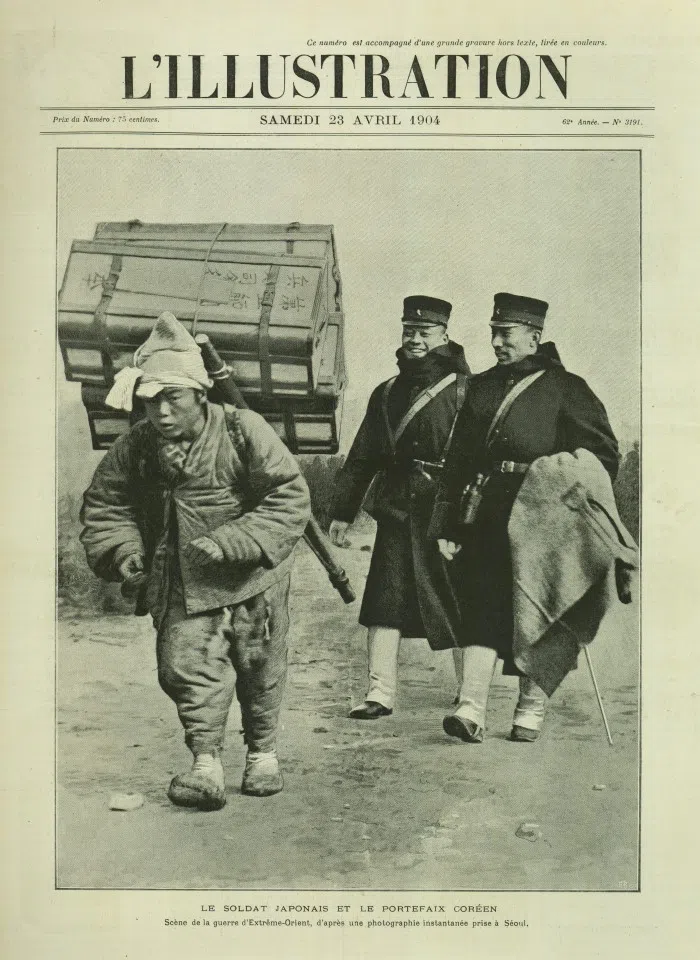

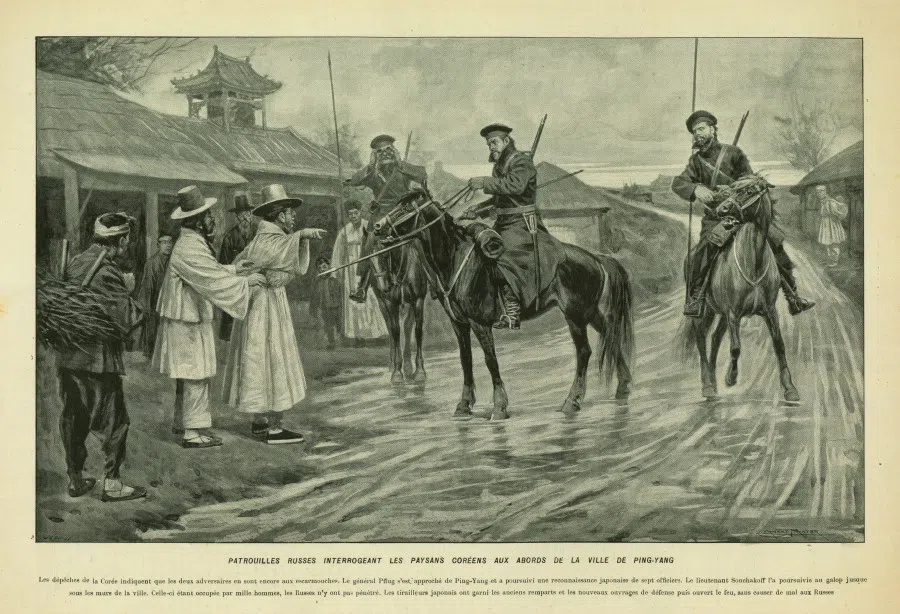

In 1905, after the Russo-Japanese War, Japan was in complete control of the Korean peninsula. In 1909, Resident-General of Korea Ito Hirobumi was assassinated by Korean activist An Jung-geun at the Harbin Railway Station.

Anti-Japanese activists fled to China

In 1910, Japan had completely swallowed up Korea, and Kim was arrested and charged in connection with the attempted assassination of Terauchi Masatake, Japan's governor-general of Korea. He was sentenced to 17 years in prison, but released after three years during the pardon following the death of the Meiji emperor.

In 1919, the March 1st Movement swept the Korean peninsula, after which many anti-Japanese activists fled to China. That same year, the KPG was established in Shanghai with Syngman Rhee (Yi Seung-man) as chairman; Kim Gu was in charge of the police. Subsequently, Rhee went to the US, and Kim carried out the actual work. Kim established a "suicide squad" - the Korean Patriotic Corps - showing the fearless fighting spirit of the Korean people.

In 1932, a bomb assassination planned by Kim and executed by Yun Bong-gil killed Shanghai Expeditionary Army commander Yoshinori Shirakawa and Teiji Kawabata, head of the Japanese Residents' Association of Shanghai, in Shanghai's Hongkew/Hongkou Park (now Lu Xun Park).

Commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy Third Fleet Kichisaburo Nomura, commander of the Imperial Japanese Army's 9th Division Kenkichi Ueda, Japanese envoy to Shanghai Mamoru Shigemitsu, Shanghai consul-general Kuramatsu Murai, and secretary-general of the Japanese Residents' Association of Shanghai Tomono Mori were maimed or injured.

The incident rocked the world, and the valiant deeds of the Korean suicide squad also shocked the Japanese, so that the Japanese government made Kim Gu its number one wanted man.

Kim's brave deeds won the admiration of the ruling party and opposition in China, as well as the praise of Chiang Kai-shek, who met Kim in secret and agreed to provide funds for Korean volunteers, and send Korean youths to army and air force military schools in China, with dedicated classes to train Korean military talent.

The KPG threw itself into anti-Japanese efforts together with China's Nationalist government. In 1937, the resistance war broke out in earnest and the KPG moved several times along with the Nationalist government, ending up in Chongqing.

In 1940, the Korean Liberation Army (KLA) was established, with Ji Cheong-cheon as commander-in-chief.

Ji graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy and escaped to Manchuria after the March 1st Movement, and joined the armed resistance against the Japanese. After the Pacific war broke out, the KLA joined the international anti-fascist camp - its main work was to incite defection among the Japanese troops of Korean origin.

North and south

In 1943, the day before the Cairo Conference, Kim Gu pushed hard for Chiang to confirm at the meeting that the Korean peninsula would be independent after Japan's surrender. Indeed, the Cairo Declaration stated that following the war, China would take back Taiwan, and the Korean peninsula would be independent. The KPG gained an important diplomatic victory, and the Cairo Declaration became the basis in international law for Korea's national sovereignty today.

However, even though the Korean volunteers who fought and sacrificed for decades against the Japanese were preparing for a glorious restoration of their country, the shadow of the Yalta accords between the US, Britain and Soviet Union loomed large.

The accords allowed the Soviet army to enter northeast China and the northern part of the Korean peninsula, leading to a split between North and South Korea after the war. Kim strongly objected to the split, and joined a meeting between north and south held in Pyongyang. In June 1949, Kim was assassinated by a right-wing soldier while at home.

In 1950, the Korean War broke out, and after three years of hard war, the north and south remained divided.

In 1960, Syngman Rhee was forced to step down and left for the US; the following year, Park Chung-hee became the president of the Republic of Korea (ROK) - South Korea - after staging a coup against Yun Po Sun who had replaced Rhee, and set straight the legacy of the ROK.

Back in 1921, Rhee went to the US to engage in talks towards independence, but it was his countrymen who were at the front line for decades in China, bleeding and sacrificing while facing Japanese guns and cannons.

So, historically, the governance of the ROK should be traced from the March 1st Movement, to the provisional governments in Shanghai and Chongqing, to the ROK government established on returning to Korea following the successful revolution.

In 1962, Kim Gu was posthumously honoured by the Park Chung-hee government as the father of modern South Korea, with a museum/memorial and statue dedicated to him. For decades after, Kim's historical image grew and he was respected by the Korean people, including in North Korea. Kim Gu symbolised the Korean people's fighting spirit in resisting Japan, and the spirit of pursuing reconciliation.

Finally, to close with some extracts from the memoirs of historian and former KLA officer Kim Jun-yop, which offers a vivid reflection of the sentiments of the Korean resistance against the Japanese in China.

On returning to Korea from China, Kim Jun-yop released his memoirs My Long March (《我的长征》). He was born in 1920 and studied at Keio University in Japan, and was then conscripted as a student soldier and sent to the battlefield in China. He quickly left the Japanese army and made the long journey to Chongqing, where he joined the KLA. The book is his autobiography and a bestseller in Korea. The Japanese translation was released in 1991, and a Chinese translation in Shanghai in 1994.

. . . . . .

When I was interpreting for Japanese POWs, I did not use honorifics or polite speech at all, but low language. The Chinese language is not like Korean and Japanese in distinguishing between respectful and disrespectful forms, but I intentionally used low language with Japanese POWs. That Japanese air vice marshal was over 50 years old, and many Japanese POWs were older than me, and it was especially satisfying for me not to use honorifics with them. Actually, humans are all alike. The so-called "Japanese spirit", "yamato", and "bushido", are in fact all language to look strong on the outside while being vulnerable on the inside. These Japanese POWs were all afraid to die - as long as we did not kill them, they were willing to do anything. How were Japanese any better than others? Did they not have to be deferential and obedient to the Chinese commandants and us young Koreans? As individuals, we should not look on them with contempt. They have been sacrificed for Japanese militarism; they were conscripted to China and became POWs, and are to be pitied.

. . . . . .

Once the truck drove through the camp gates, over 100 comrades of the KLA rushed over, welcoming us with warm applause. Although this was the first time we met, we were all descendants of Dangun (legendary founder of Korea); we were all fighting to liberate our homeland, we all had the same dream, and it was like we were old friends - we were very moved. In the 14 months since leaving Pyongyang, I had worn the uniforms of the Japanese, Chinese and US armies; it was difficult to control my emotions at the thought of the training that was to begin the next day, and going home to engage in underground work. The thought of the home I had not seen for so long, and my mother and siblings whom I had missed - it was indescribable homesickness. I drifted off to sleep with these thoughts.

. . . . . .

Over the vast expanse of white waves, little islands showed. Ah! This was the sea around Incheon, that was forever in our dreams. In that instant, we started cheering, forgetful that the Japanese fighter planes could attack at any time. The sky was clear and cloudless; the sky and sea were one. The sky was such blue, and the sea was also green enough to look blue; water and sky were the same colour. General Lee sat between me and Chang Chun-ha; I noticed that he kept wiping his teary, red eyes with his handkerchief. He had been away from the motherland for 37 years - how could he keep from weeping at returning to its embrace?

. . . . . .

At the time, the Chinese government totally approved of and supported the plan for the KLA to return home, while the US position remained unclear. My view then was that since the US only allowed even President Kim Gu to return as an individual, how would they allow an expanded KLA to return as an armed force? China and Russia had a clear understanding and policy when it came to the Korean peninsula, but the US could not reach that level and made a major mistake. If the US had actively supported the KPG and allowed the 100,000-strong KLA to quickly return home fully armed, there would have been no split between north and south.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)