Ordinary people, extraordinary life (Part I): Tang Jinglin

(Video and text) The story of a teacher farmer who worked hard his whole life to finally live in the city. Yet, a part of him will always remain with the fields. "A farmer can never be separated from his land at any time. Peace of mind comes only with land ownership," he says.

From 1949 to 2019, China underwent a tremendous transformation. The historical events of the past 70 years have left no Chinese person untouched. The ups and downs of lives that are easily overlooked can serve as leads for fleshing out a broader narrative - one that runs from the establishment of the PRC through the Chinese economic reform and on to the new era beyond.

Looking back on the past, these people were the witnesses of history who experienced it firsthand. Looking ahead, they are the ones who drive and create the future.

Here are the stories of five ordinary Chinese as a retrospective survey of the last seven decades of change - the greater story of China as told by individuals amongst generations of its people.

Tang Jinglin: The teacher farmer's long march to city life

At age 73, Tang Jinglin still remembers clearly the day in 1979 when baochan daohu (fixing of farm output quotas on a household basis) took effect in his village, even though it happened 40 years ago.

"It was dawn. I got up to start working in the fields under my charge. There was a serious drought that year, making the ground too hard for ploughing. I had to dig with a hoe, using great force."

The land was the same as before, but feelings were different then. After sustaining himself on food from the communal canteen for 20 years, he felt a sudden sense of urgency about labouring for his own sake.

Tang Jinglin is a native of Fengyang County, Anhui Province, a county that was home to Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty. Historically, the area has been known for frequent natural disasters, the ravages of war, and general poverty. "Let's talk about Fengyang. It was a good place, Fengyang. Nine out of ten years here are lean, as it has been since Emperor Zhu." Centuries of hardship suffered by the people are depicted in these lyrics from the traditional folk song "Flower Drums of Fengyang", which is familiar to most Chinese people.

All of us were poor

After establishing the PRC in 1949, the Chinese Communist Party proceeded with land reform, whereby property was distributed to farmers who owned little or no land. The gratitude felt by the older farmers from that time is still alive today. For example, a portrait of Mao Zedong, the nation-founding leader of the Party, still hangs in the bedroom at Tang Jinglin's residence as an expression of gratitude for how Chairman Mao "defeated the local tyrants and divided the land".

In the two decades prior to baochan daohu, Chinese villages went by the people's commune system, in which all means of production (including the land itself) were owned by the commune. This nullified the farmers' right of autonomy and management over the land, rewards were not tied to labour invested, which ultimately impaired the peasantry's enthusiasm for production and seriously hindered economic development.

18 desperate farmers risked imprisonment and a penalty of death, leaving their handprints in blood on an epoch-making agreement. The agreement concerned the division of the local commune's land into family plots, and it marked the beginning of China's Agrarian Reform.

Life was just as hard for Tang's family as it was for other villagers in Fengyang. Today, he rummages up old photographs from 40 years ago and goes down memory lane, saying, "There were ten of us-my parents and siblings-living in four thatched huts. We were not the only ones. Nine out of ten households were poor."

Each year, once the autumn harvest was done, the local villagers had two options. They either stayed at home and ate porridge so watery that they could see themselves reflected in it, supplemented with salted vegetables, or they went out to beg in desperation.

In 1978, the entire province of Anhui, inclusive of Fengyang County, was hit by a great drought. In the county's Xiaogang Village, which had been struggling against starvation for many years, 18 desperate farmers risked imprisonment and a penalty of death, leaving their handprints in blood on an epoch-making agreement. The agreement concerned the division of the local commune's land into family plots, and it marked the beginning of China's Agrarian Reform.

The Xiaogang villagers' clandestine land contracting gained the support of pro-reform leaders like Deng Xiaoping. Pilot programmes along the same lines were then initiated in various places.

Tang Jinglin still remembers a ditty popular in Fengyang County during that time, "Dabaogan (household-based contracting), dabaogan, it's a wholly straightforward way! Some for the State, some for the people, and you may keep the rest!"

My land and my brick house

Tang's municipality Damiao Town was approximately 20 miles away from Xiaogang Village. A year after the village went ahead with the household-based contracting of agricultural production, the same system was introduced in the town after the autumn harvest in 1979.

A refreshing change subsequently came over the local villages like nothing ever seen before. "The weeds used to be taller than the wheat seedlings. But later, weeds could no longer be seen in the fields, not a single blade. More people came to labour there - not only youngsters, but also the elderly. Gone was the lack of diligence seen in the past, as were the excuses of being too sick or old. Every household was putting money together to purchase chemical fertilisers, which very soon failed to keep up with the demand. Farming tools went out of stock too."

"Wheelbarrow after wheelbarrow of grain was transported back and piled up to the beams. With nowhere else to store it, we eventually had to pile it up outside the door, just beneath the windows. Tell me, how could we not be delighted?"

Some of the farmers were so eager to boost their production output that they went to outrageous lengths. In this era before farming machinery, the agricultural output of the land was mainly dependent on working oxen. There were farmers who turned the mills day and night, working their oxen to death. On the other end of the spectrum, there were those who valued their oxen more than anything else, hoping to maximise their stamina during the spring ploughing. Eggs, usually too precious to be served to their own family, were thus sometimes fed to these animals. In some cases, farmers even fed their oxen stewed chicken.

Tang Jinglin was in his early thirties when his family of ten took charge of about 2.1 hectares of land. Although he cannot recall with certainty how much food they had produced each year after the new system was in place, the exhilaration felt at that time remains incredibly vivid. He says, "Each mu (1 mu = 0.0667 hectare) was yielding an additional four or five hundred kilograms. Wheelbarrow after wheelbarrow of grain was transported back and piled up to the beams. With nowhere else to store it, we eventually had to pile it up outside the door, just beneath the windows. Tell me, how could we not be delighted?"

"Fill the barn with crops in a year, slaughter a pig or goat in two, switch from a thatched house to a tile-roofed house in three." This popular verse was a true reflection of how many rural areas in China were progressing after the advent of household-based contracting.

That baochan daohu increased rural production efficiency by a great deal was plain for all to see. When the Central Committee of the CPC issued the document looking into "Issues for further strengthening and perfecting the agricultural accountability system" in September 1980, the new system that was executed in many provinces across the country spread like wildfire. In 1982, another Central Committee's No. 1 Document officially gave the so-called "household contract responsibility system" a thumbs-up. Household-based contracting henceforth became a basic policy for China's rural communities. The people's commune system initiated in July 1958 was finally officially abolished in 1983.

The people no longer went hungry, and life had improved significantly. Even so, they were still a long way from affluence.

Tang Jinglin was actually not just a farmer. He was also a minban teacher-a rural community teacher with no relevant state-recognised certification-at Sanyang Village, Damiao Town, Fengyang. He had to both farm and teach, which meant he could not divert more energy to agricultural production like the fervent villagers did. What he could do was "grow crops like soya beans and sesame on the ridges or trails between the fields and in every nook and cranny".

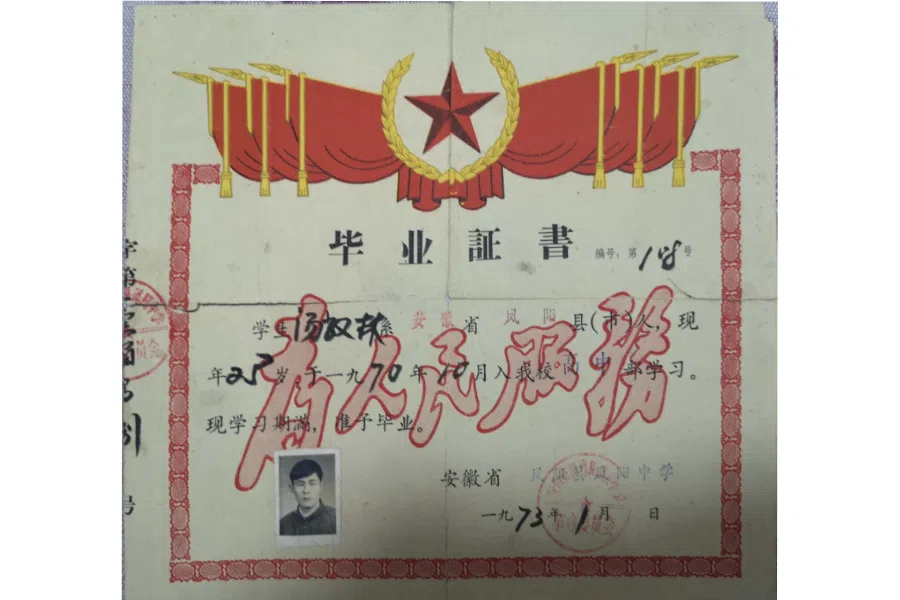

Despite having engaged in agricultural work since childhood, he had left the village to study for six or seven years and completed his education at a senior middle school. He admits that he was not as capable as the villagers who laboured under the sun day after day and had never left their land.

"None of the friends and relatives who hurled sarcasm at me in the past could imagine this - that a man who was raising his child alone would be able to build his own tile-roofed brick house."

In 1984, Tang's wife, who came from a relatively affluent neighbouring county, abandoned their eight-month-old daughter and left. It was a crushing blow to him.

Tang raises his voice as he says, "My temperament was such that I would never easily admit defeat. I told myself that I had to build three large tile-roofed houses for myself someday. I was not going to let the other villagers think little of me."

It took Tang three years of austere money-saving and a sum of 10,800 RMB, but in 1987, he finally built the house of his dreams. Very pleased with himself, he says, "None of the friends and relatives who hurled sarcasm at me in the past could imagine this - that a man who was raising his child alone would be able to build his own tile-roofed brick house."

However, the great current of history can often arbitrarily alter the fates of ordinary folks.

The 1970s saw the Chinese government picking up the pace in its efforts to eliminate illiteracy throughout the country and dramatically expand its army of minban teachers. Tang Jinglin, who graduated from senior middle school and was serving as an accountant in his production team, was granted approval to work as a minban teacher. In China's education system, such teachers were not part of the state's official network of certified schoolteachers. They were counted as farmers, even though they shouldered the duties of teachers. Apart from earning ten workpoints a day, the same amount one could normally earn as an able-bodied labourer in a production team, Tang Jinglin also received a monthly allowance of 2 RMB (about 0.4 Singapore dollars). At a time when most other villagers could only earn a maximum of 10 workpoints per day, this was quite enviable and, indeed, an achievement he was proud of.

After household-based contracting was implemented, Tang continued to devote himself mostly to elementary school teaching, as well as literacy teaching for villagers at a part-time school. He even received a certificate of merit as recognition for his work in these areas.

Just when he was looking forward to ascending to the next level in his teaching career, a major rectification of China's entire system of minban teachers unfolded. Tang became one of more than 2 million people dismissed from service. In theory, the systemic overhaul, which resulted in the dismissal of unqualified teachers, was carried out according to the fundamental five-pronged policy (i.e., closure, conversion, recruitment, dismissal, retirement) stipulated by the state, but there was some unfairness in the actual execution process on the grassroots level, with some people getting what they wanted through special connections.

During our interview, it is clear that the old man is still angry about being fired in 1992. He takes out the certificate of merit he received three decades ago and fumes, "It says here that I 'teach and nurture others', that I am 'a paragon worthy of emulation'. That proves that I was a competent, fine minban teacher. What reason could they have for firing me?"

I am a city-dweller!

Tang lost his wife as a young man, and later lost his job when he was already middle-aged. Life was hardly a bed of roses, but as often happens, a window opened when the door closed. In 2001, Tang met another elementary school teacher, one who was to become his wife. His only daughter successfully enrolled in a vocational secondary school. Two years later, Tang and his wife moved into a public rental unit of some 50 square metres at the Zhonglou Housing Estate in the county seat of Fengyang. With this, he began to "enjoy a city-dweller's life which had been unimaginable in the past".

In the interview, Tang Jinglin and his wife say that they are contented. The husband enjoys a social security income of 1,621 RMB a month, while his spouse receives a retirement pay of 3,768 RMB for having served as a state-recognised elementary school teacher.

Due to health issues, Tang has not been able to work in the fields for the last two years. His contracted land is now under the charge of his younger brother. Despite having retired from farming, Tang and his wife still return to his village once every ten days or so, just to look at the land registered to his name.

"A farmer can never be separated from his land at any time. Peace of mind comes only with land ownership," he observes.

![[Big read] China’s 10 trillion RMB debt clean-up falls short](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/d08cfc72b13782693c25f2fcbf886fa7673723efca260881e7086211b082e66c)