Us and them: Lessons from ancient China about demonising 'enemies'

At a time when the world is forced to recognise that the earth is now really a village, the idea of a foreigner is rapidly transforming into that of a neighbour. In the late 14th century it took the plague several years to go from Istanbul to Spain. In the present, it took the coronavirus only a few weeks to travel from China to Europe and back. Can this coronavirus pandemic let us rethink how we treat foreigners, and whether and how our attitude toward foreigners reflects our character and our values as a person, a community, or a nation?

...it is often assumed that the tendency to construct and preserve individual and group identity is one of the measures that a group of people depend upon for their survival.

It may be the case that this pandemic is strengthening divisions between nations, since it is deemed so important that every nation is to keep a stern control of the border, and to distinguish "us" and "non-us". Or, could it be the other way round, that we are all learning the lesson that only by treating the foreigners as close neighbours can we see the world as a village and help each other to get through difficulties during disasters, natural or man-made? A look at the attitude toward foreigners in an earlier time, nevertheless, may give us some perspective on our current situation.

What it meant to be a foreigner in the past

The last few decades have seen a surge of awareness of the global nature of contemporary developments in all aspects: economics, finance, technology, and the underlying intellectual exchange. The movement of people across the borders became more frequent than ever. Yet it is also clear that modern political boundaries do not necessarily coincide with ethnic boundaries, and that ethnic conflicts persist in many parts of the world partly because of the drawing of artificial boundaries that intensified mutual misunderstanding and even hostility. How did these unfortunate situations develop?

Besides the possible manipulations of strong powers who utilise ethnic tensions for other purposes, a familiar line of interpretation is to see in human nature a basic tendency to distinguish between "us" and "them" or "self" and "others". In other words, it is often assumed that the tendency to construct and preserve individual and group identity is one of the measures that a group of people depend upon for their survival. This assumption may be true to a certain extent, but it is certainly not the whole truth, as can be demonstrated by looking at the past.

However, the key concept that needs to be clarified first is the very term "foreigner": what is the meaning of this term? In what context is the term usually employed, and with what intention?

In our modern parlance, a foreigner refers to someone from another sovereign state, whose status in relation to the one who uses this term can be clearly defined in legal terms. A foreigner cannot enjoy many privileges that a citizen supposedly can. Yet, on the other hand, a foreigner can have certain exemptions from the rules that are applied to a citizen. It is in any case mainly a legal concept that recognises the modern nation-state.

Such a modern usage of the term is understandably not quite suitable for discussing the ancient world. If we look at the Latin origin of "foreign", we see that it comes from the term forās, meaning "outside". Thus, its basic meaning should be "outsiders", that is, people outside of a certain circle, be it geographical, social, political, or cultural. We should look for terms that can best fit this meaning of outsiders in the ancient world.

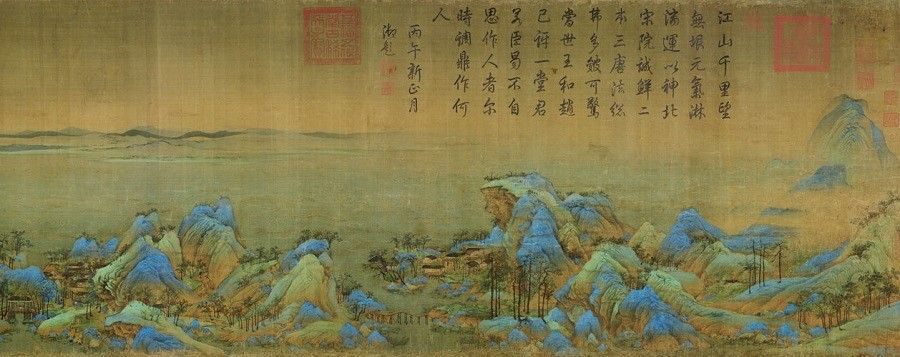

A geographical distinction in ancient China

In early China, during the Shang period (c. 1570-1045 BCE), the foreign tribes or states were referred to with specific names such as Guifang (鬼方), Gongfang (贡方), Tufang (土方), Qiangfang (羌方), etc. The term "fang 方" refers to regions outside of the Shang political control.

Among the different fang, the Qiangfang interacted with the Shang most frequently. The etymology of the term qiang (羌) is most likely related to the word for sheep or goat (羊), thus the Qiang people were probably the goat-herding nomads in the western regions. It is both a name for a specific group of people, and a general appellation referring to a number of nomadic tribes.

The use of the term "zhong" (中) which means "the centre" clearly shows the self-centric view expressed in geographical terms.

This situation further developed during the Zhou period, when some fixed terms were employed to designate the foreign tribes that scattered among and around the Central Plain states (now conventionally referred to as China). These included Rong (戎), Yi (夷), Man (蛮), and Di (狄) - all were general designations referring to the foreign tribes. Later texts tend to assign specific directions to them, thus West-Rong, East-Yi, South-Man and North-Di. The implicit result is to place the Central Plain states in the centre of the known world. As with the case of the Qiang in the Shang period, these terms are more geographic rather than ethnic designations.

These examples indicate that the ancient Chinese people made certain distinctions between "us" and "others" by giving specific names to certain groups of foreign people. An element common to all of these terms is the geographic reference: the people of the outside region or fang, or Qiang, the goat herders of the mountains or steppes.

In ancient China, terms for "foreigner" are often synonymous with "enemy".

In tandem, the self-designation of the Chinese also hinged upon geographic reference. The term Zhongguo (中国) or "the Middle State" became the choice of self-designation for the Zhou court and its vassals that occupied the Zhongyuan or "Central Plain". The use of the term "zhong" (中), which means "the centre", clearly shows the self-centric view expressed in geographical terms. It seems that for these ancient people, geographic distance and relative position could have been a factor that registered a certain difference between them and the foreigners.

As all appellations appear in contexts, when groups of foreign people are mentioned in the ancient sources, they usually reveal certain attitudes of those who left the sources. One common theme associated with foreigners is to depict them as enemies. In ancient China, terms for "foreigner" are often synonymous with "enemy".

Thought of as a true or close-to-real record of the history of the Spring and Autumn period, the Zuozhuan (左传) presents basically two kinds of views toward foreigners: one pacifist, the other militant. The militant view takes a more confrontational position and demands the submission of the foreign tribes. This is represented by a famous sentence of Guan Zhong (管仲), the Prime Minister of the state of Qi (齐): "The Rong Di are wolves, to whom no indulgence should be given; within the Xia (or Central Plain) states all are nearly related, and none should be abandoned."

It should be clear that most sources that see the foreigners as hostile or even demonic opponents bear a certain degree of the official attitude, and most likely with the intention of mobilising internal forces for specific purposes or supporting the legitimacy of the political power.

One passage from the book of Mencius, a collection of sayings by Mencius (孟子), a Confucian thinker of the Warring States period, articulates aptly the subtle relations between foreign enemies and the internal unification and survival of a state:

If a prince have not about him his court families attached to the laws and worthy counsellors, and if abroad there are not enemy states and foreign invasions, his state is bound to destruction.

Mencius' original intention was to warn against the possible dangers arising from easy and wanton lifestyles because of peace and prosperity. Foreign invasions stimulate people to be on guard against moral lapses. Conversely, a presumed or even fabricated foreign enemy and rival state could become the pretext for a government to call for internal unity, which often means the sacrifice of individual property and liberty for the sake of collective security. Mencius' insight inadvertently points to a common political phenomenon which is particularly revealing in light of the current Covid-19 pandemic situation.

A simple model that portrays a constant antagonism between "we" and "they" therefore, is unlikely to reveal the historical reality.

Demonising past and present

It should be clear that most sources that see the foreigners as hostile or even demonic opponents bear a certain degree of the official attitude, and most likely with the intention of mobilising internal forces for specific purposes or supporting the legitimacy of the political power. Moreover, the foreigners were often depicted in contrast with those who left the description as being without culture, that is to say, without the lifestyle of the sedentary people such as the Chinese. A most interesting passage in the Zuozhuan reveals an attempt at making a cultural distinction between the Chinese and the foreign tribes:

We Rong people's food and garments are different from those of the Chinese (Hua 华) people, and ...Our language does not allow us to communicate (with the Chinese people).

The intriguing thing about this paragraph is that it is presented as spoken by a Rong chieftain, on the occasion of an alliance meeting between the state of Jin and the Rong tribe to the west of Jin. Although we cannot really establish the historicity of this passage, we can at least say that language and lifestyle were recognised by the Chinese author of the text as the criteria that distinguished the two peoples. On the other hand, we can also see that such differentiation was a view from "the centre", which was most likely a cultural construct that tried to internalise and rationalise unfounded biases.

Yet this could not have been the whole story. As a contrast, we also notice that in different social, political and cultural contexts, representations of foreigners were not necessarily negative. Reviewing the interaction of a people with outsiders or other peoples, one might find that in reality peaceful relationships far outweighed confrontations. The seemingly strong animosity toward foreigners might have been confined to officially proclaimed policies and representations, while the day-to-day interactions between common people and foreigners could not have been in a constantly hostile situation. In terms of politics in practice, moreover, a peaceful relationship with foreigners was most of the time desirable for the political leaders.

...human society does not always act in its own best interest...

In the case of China, although textual evidence suggests that confrontations existed between foreign tribes and the Zhou state, it is also clear that the Zhou and the barbarians were not necessarily always in a hostile relationship. They were probably more practical in dealing with the outsiders than the idealised records would have us believe. A simple model that portrays a constant antagonism between "we" and "they" therefore, is unlikely to reveal the historical reality. In fact, the Central Plain states of the Eastern Zhou period had always tried to keep a peaceful relationship with the strangers at the gate.

This balanced yet more private attitude, although representing at least part of the historical truth, seems never to have had the chance of exerting major influence on the later course of history. These two attitudes - one official, self-centric and self-aggrandising, and the other private, realistic and with more sympathetic understanding - given a certain degree of oversimplification, can be seen not only as constituting part of the "group psychology" but also as symbolic representations of the ambiguity of human nature.

It is perhaps only by admitting the complexity of human nature, that, despite individual revelations of the equality of humanity, taken as a whole, human society does not always act in its own best interest, that the mixed attitudes toward foreigners presented by the ancient cultures becomes more comprehensible and provides us with some food for thought.

Returning to the present Covid-19 pandemic, it seems clear that while the leaders of nations are busy with preventing foreign invasion of the coronavirus, it would be best to abandon the attitude of treating the foreigners as enemies and begin to treat each other as good neighbours. The official attitude pronounced by the political leaders needs to take heed of the private sentiments of the people who often have direct evidence to show that the foreigners are more friendly than one instinctively assumes.