China in the Gulf: India overmatched but undaunted

The widely noticed draft agreement between China and Iran for developing a comprehensive partnership in the energy, economic and security spheres over the next quarter of a century, presents India a higher level of challenge to India's engagement with the Gulf region. The deal is certainly not imminent and there are many imponderables before the promised Chinese investments of US$400 billion begin to flow into Iran. The draft agreement nevertheless points to the significant geopolitical discontinuities unfolding in the Gulf.

Both China and India have had historic connections to the Gulf over the millennia. But in the modern era, India has been far more central to the politics of the Gulf - thanks to its physical proximity, shared cultural heritage, and the natural flow of goods, people and ideas between the Indian subcontinent, Persia and the Arabian peninsula. China in contrast was a familiar but distant entity, both physically and culturally, for the Gulf in recent centuries. In the 21st century, however, as in so many regions far from its shores, China is all set to become a far more powerful force than India in the Gulf. This is inevitable, given China's new status as the world's second most important power.

India had to continually fend off Pakistan's outreach to the Gulf in the name of Islam.

China moving ahead of India in the Gulf

As the successor to the British Raj, independent India inherited an expansive imperial tradition in the Gulf. India's first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru broke away from the Raj legacy, and deliberately refocused India's engagement with the region on the ideals of Asian unity, Arab solidarity, and a rejection of Western hegemony. Although this policy of non-alignment generated much good will for India, Delhi was increasingly out of sync with the region's hard-boiled realpolitik. On top of this, Delhi had a special problem in the region to deal with that arose from the partition of the subcontinent - India had to continually fend off Pakistan's outreach to the Gulf in the name of Islam.

After the energy crisis, the natural interdependency between India and the region came to the fore. If the dramatic rise in oil prices in the 1970s broke the back of the Indian economy, they also opened the door for massive labour exports to the Gulf that fetched large hard currency remittances.

China's entry in the region complicates India's prospects in the region.

India's own economic boom in the 21st century meant that it has become one of the top importers of energy from the region and a major exporter of goods. India's rise as a great power provided the basis for a less ideological approach to the region. Delhi largely succeeded in separating itself from Pakistan, whose economic prospects steadily declined in the 21st century. India's GDP, at US$3 trillion, is now nearly ten times larger than that of Pakistan (US$300 billion).

Over the recent years, Indian diplomacy has patted itself on the back for cultivating good relations with all major actors in the region, many of whom have big problems with each other. But China's entry in the region complicates India's prospects in the region. Five issues stand out.

Obstacles and opportunities

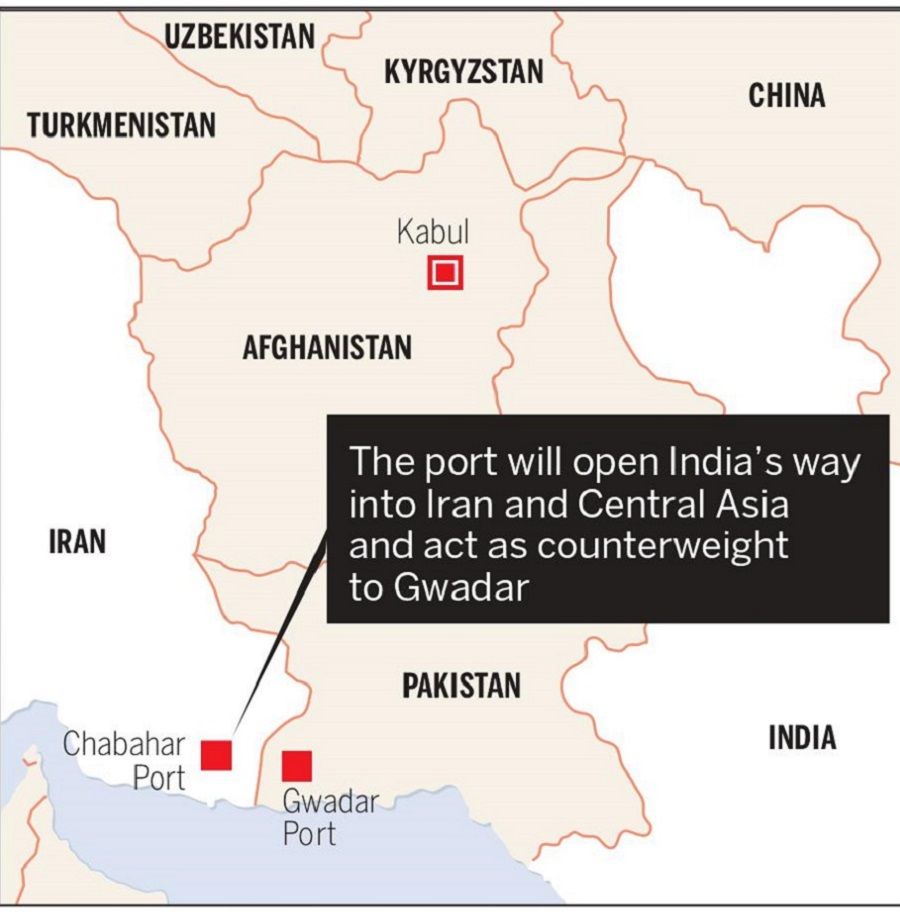

First, over the last decade, India has sought to accelerate the construction of the Chabahar port on Tehran's Arabian Sea coast, as a rival to China's development of a massive port complex at Gwadar just across Iran's frontier with Pakistan. But if Tehran consolidates the planned partnership with Beijing, Delhi could be easily edged out of Chabahar and other strategic projects in Iran.

Second, India's ability to engage in economic competition in the region with China is overstated in the current context. China's economy today is nearly five times larger than India's - the GDP figures are US$15 trillion and US$3 trillion respectively. While India does undertake small infrastructure projects in the region, it is nowhere near the commercial scale - for example the planned US$400 billion for Iran - that China's Belt and Road Initiative can bring to bear upon the region.

Unlike India, China boasts of a large and increasingly sophisticated military industrial base that has contributed to Beijing's emergence as a major arms exporter to the world. Some of those flows are directed at the Gulf.

Third, as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, China has the kind of leverage that eludes India in the region. As the Gulf security issues forever draw international attention and scrutiny, China can convert its diplomatic clout into tangible political outcomes, for example by offering protection from the UN sanctions regime.

Fourth, beyond diplomatic protection, China's ability to provide military support has begun to increase. India, in contrast, has struggled to develop security cooperation with the Gulf. Unlike India, China boasts of a large and increasingly sophisticated military industrial base that has contributed to Beijing's emergence as a major arms exporter to the world. Some of those flows are directed at the Gulf.

That China's first foreign military base has come up at Djibouti next door to the Gulf signals China's arrival as a potential military power in the region. This is reinforced by the speculation that China's Gwadar project in Pakistan has a military dimension and that some of the planned port projects in Iran might be designed for dual - civilian and military - use.

Fifth is the shifting role of the US in the region. For long the main security provider in the Gulf, America's role in the region looks increasingly shaky and complicates the calculus of both Delhi and Beijing. For India, a deepening strategic partnership with the US offers potential means to strengthen its position in the region, but it also complicates Delhi's regional policy given America's continuing conflicts in the region.

India is also aware that the complexity and diversity in the Gulf will guarantee India's own expanding role in the region.

China, on the other hand, may find its prospects in the Gulf clouded by its deepening conflict with America. Even if it undertakes some retrenchment in the Gulf, the US is likely to remain the most influential external actor in the region and could easily trip up China that is new to the volatile geopolitics of the Gulf.

Delhi is realistic enough to know that it is unwise to embark on a geopolitical competition with Beijing in the Gulf. Its current emphasis is on playing to its own limited strengths. Delhi knows enough about the Gulf to recognise that it is rather hard for external powers to comprehensively dominate the region. India is also aware that the complexity and diversity in the Gulf will guarantee India's own expanding role in the region.

Related: Deepening China-Iran relations could change global geopolitics | China and India: When Western democracy fails and only utopia remains | India losing Nepal as China-Nepal relations strengthen | Uneasy Dance between an elephant and a dragon: 70 years of diplomatic relations between India and China