India gets ready for shifts in US-China relations under Biden

Much in the manner that a poor and a turbulent China became a critical element in the US-Soviet competition during the 1970s, even a weak India could have some bearing on the evolution of the Asian balance of power, vis-à-vis US-China relations, says Prof C. Raja Mohan. In recent years under the Trump administration, Delhi ended its historic hesitations about deeper military and security cooperation with the US by embracing the Indo-Pacific strategy and helping to revive the Quad. What will be the future direction of India-US relations under the new Biden presidency? What would that mean for China?

As Joseph R. Biden prepares to take charge of the US in the third week of January, there is little doubt that China will be at the top of the foreign policy priorities of the new administration. Biden's China theorem will now have an interesting corollary - the growing US partnership with India that the new president inherits from his predecessors. President Donald Trump's Indo-Pacific strategy had inserted India firmly into the equation between US and China.

How Biden takes that forward will be of much interest in Asia and more broadly the Indo-Pacific. Biden has long experience of international affairs - as vice president in the Obama Administration and through his long service in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Biden has a strong record of engagement with both China and India and is expected to fashion a policy towards them that is more stable and institutionalised, in comparison to Trump's personalised strategy by tweet.

The weakest leg of a triangle could make a strong impact

China has long been the most important bilateral relationship for the US. After all, China is the world's second largest economy after the US. The People's Republic of China also has the world's second most powerful armed forces. China figures prominently not only in America's bilateral relations but also affects all major global issues of concern to the US - from trade to climate change and from alliance relations to multilateral institutions.

India has been marginal to these concerns until recently. But thanks to India's rise, much slower and more tentative than China, Delhi's weight in Washington's economic and geopolitical calculus has steadily risen. But it is by no means set in stone; India is likely to remain well behind the US and China for quite some time. Its current GDP is at $2.6 trillion; China is at $15 trillion and the US at $21 trillion.

But much in the manner that a poor and a turbulent China became a critical element in the US-Soviet competition, even a weak India could have some bearing on the evolution of Asian balance of power.

That lends a measure of volatility to the triangular relationship. But much in the manner that a poor and a turbulent China became a critical element in the US-Soviet competition, even a weak India could have some bearing on the evolution of Asian balance of power.

That takes us back to the early 1970s, when the US dramatically altered its China policy by ending its attempted isolation of the People's Republic since it was proclaimed in 1949. As it confronted a growing geopolitical challenge from the Soviet Union, President Richard Nixon adopted the stratagem of embracing Beijing to weaken Moscow. The logic of the Sino-US political alliance began to look shaky after the crackdown on the student protestors at Beijing's Tiananmen Square in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Just as the political glue binding them seemed to loosen, the economic engagement between the two countries took off. The rapid economic reforms initiated by Chairman Deng Xiaoping in the early 1990s laid the basis for a stable relationship over the last three decades.

India could be drawn deeper into coalition against China

That structure has broken down under Trump. The US domestic backlash against free trade and economic globalisation focused inevitably on China. To be sure, Delhi was also on the receiving end of Trump's fire on trade deficits, albeit in a much smaller way. As on trade, so on climate change, Trump demanded an end to differential treatment of China and India and opposed their treatment as "developing countries".

Even as a section of the Trump administration began to talk about "economic decoupling" from China, the voices across the US security establishment to confront the geopolitical challenges from a rising and assertive China became louder. While it was President Obama who talked about the "pivot to Asia", it was Trump who turned that into a concrete Indo-Pacific strategy that calls for long-term military contestation with China.

As it faced up to China's nibbling at its disputed frontier and Beijing's political and military influence began to grow in South Asia and the Indian Ocean, Delhi ended its historic hesitations about deeper military and security cooperation with the US.

The era of turbulence in US-China relations, as it turned out, coincided with the deepening crises in China's ties with India. Delhi became increasingly anxious about growing trade deficits with China and the hollowing out of its manufacturing sector by cheap Chinese imports. Delhi cited these concerns to withdraw from the Asia-wide Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership that is to be signed on 15 November.

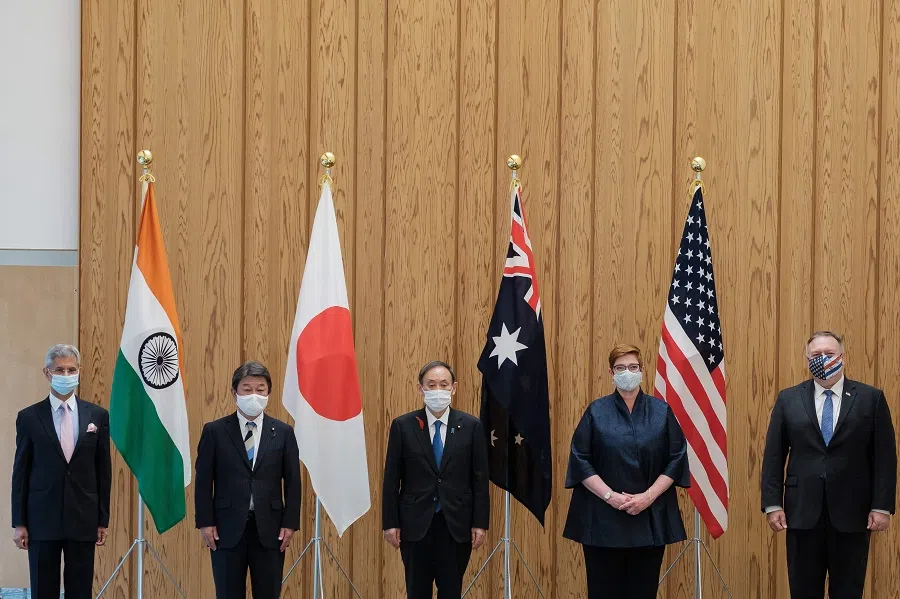

As it faced up to China's nibbling at its disputed frontier and Beijing's political and military influence began to grow in South Asia and the Indian Ocean, Delhi ended its historic hesitations about deeper military and security cooperation with the US. During the Trump years, India embraced the Indo-Pacific concept as well as helped revive the Quad, or the Quadrilateral Security Framework, with the US, Japan and Australia.

India watchful of winds of change in US-China relations under Biden

The US and Indian policies tended to be out of sync all these decades - India embraced China when the US was isolating it in the 1950s. India's relations with both declined amidst the US-China rapprochement since the late 1970s. It is only in the Trump era that a shared concern on a rising China has emerged between the two nations.

The shared anxieties between Delhi and Washington about Beijing are likely to persist under Biden. Meanwhile the conflict between India and China appears increasingly intractable and all indications are that they will head further south in the next few years. But as the weakest of the three powers, India is preparing for some inevitable shifts in the relations between US and China under Biden.

India, however, is reassured for now that Biden wants consultations with friends and allies on a more coordinated policy towards China.

Delhi is acutely conscious that the China policy will be up for contestation within the Biden administration. Wall Street and Silicon Valley, which rallied behind Biden, want an end to the confrontation with China. But the working people and progressives want to stop Biden from returning to business as usual with China and would like to see strong protection for US economic interests. The defence and security establishment would want to continue with the policy of retaining American military primacy in the Indo-Pacific.

India, however, is reassured for now that Biden wants consultations with friends and allies on a more coordinated policy towards China. It is also encouraged by a strong outreach by the Biden campaign to the Indian diaspora, which has acquired some salience in battleground states. Delhi is also familiar with most of the likely candidates who are expected to handle sensitive positions in the Biden administration. Having seen India's ties improve with the US over the last two decades on a sustained basis, Delhi is confident that it can manage potential shifts in Washington's China strategy.

Related: Bumpy ride ahead for US-China relations after the US elections | Biden presidency a turning point for China-US relations? | India in the Indo-Pacific: Reining in China in the new theatre of great power rivalry | Containing China: US and India to sign third military agreement in 'strategic embrace'