Land Bridge in place of Kra Canal: Game changer for Thailand's future engagement with region and China?

The race between two competing ideas for mega infrastructure projects in Southern Thailand has entered the final stretch. The old Khlong Thai or "Thai Canal" scheme has been overtaken by the new "Land Bridge", which enjoys crucial support from Transport Minister Saksiam Chidchob.

One key advantage of the Land Bridge is that it will offer international shippers an alternative route, bypassing the congested Straits of Malacca and shortening shipping time by about one day.

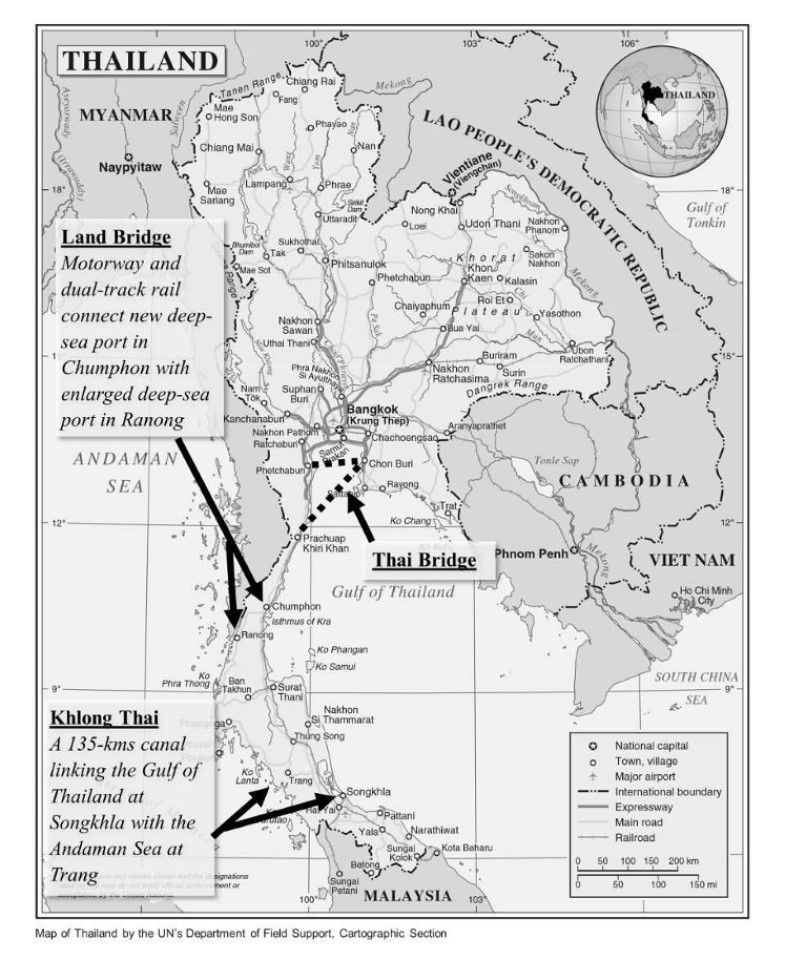

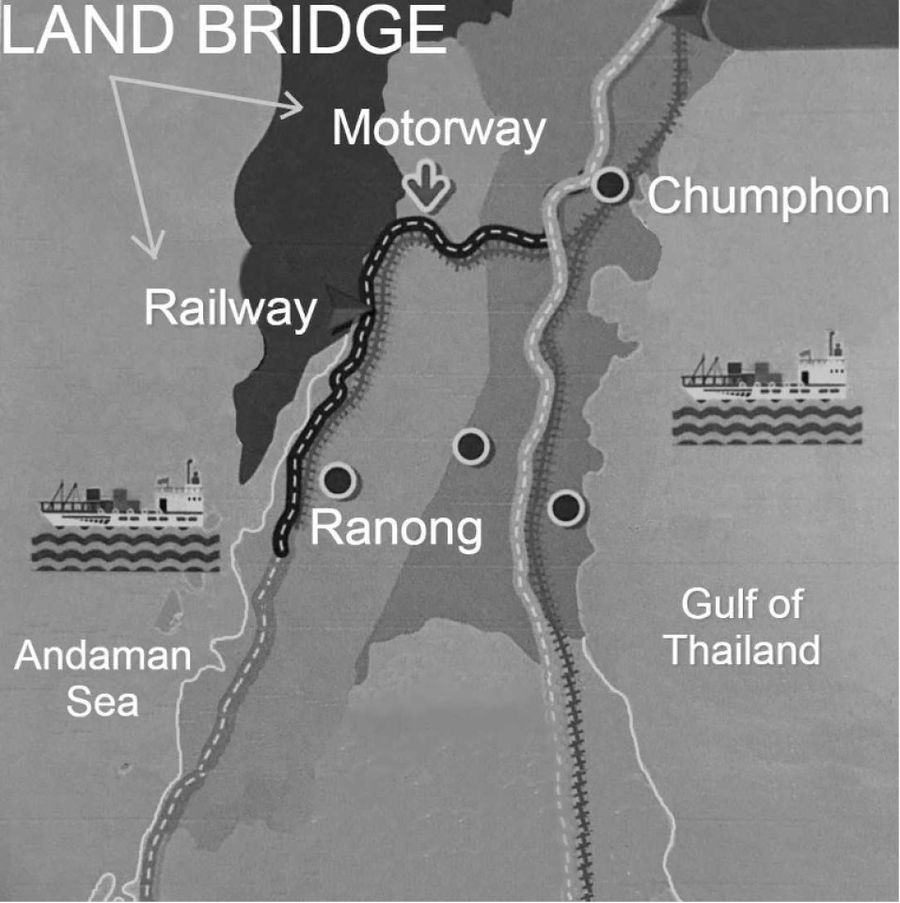

The Land Bridge project will involve the construction of a deep-sea port in Chumphon Province on the Gulf of Thailand and the upgrading of the small port of Ranong on the Andaman Sea into a modern deep-sea port. The two ports will be connected by a dual-track railway and a motorway, which will constitute the Land Bridge for the multi-modal transport of containers and goods from the South China Sea through the Gulf of Thailand to the Indian Ocean through the Andaman Sea (See Maps 1 and 2). One key advantage of the Land Bridge is that it will offer international shippers an alternative route, bypassing the congested Straits of Malacca and shortening shipping time by about one day.

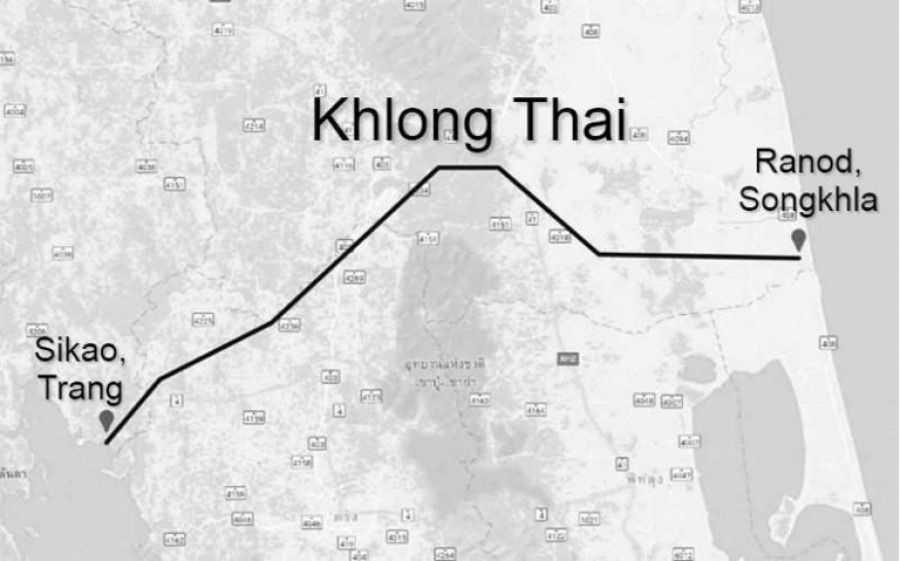

The same advantages have been the primary selling points of the Khlong Thai proposal, which is a twentieth-century reincarnation of the age-old idea of the Kra Canal. Now, the most talked-about route for the Khlong Thai is the Route 9A - which is a 135-km open canal, without locks, at least 30 metres in depth and 400 metres in width and thus allowing two-way traffic (Map 3).

The route runs from Ranod District in Songkhla Province on the Gulf of Thailand to Sikao District of Trang on the Andaman Sea. It offers a shortened distance of about 1,200 nautical miles between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, saving up to one whole day of sailing time on ships using the Straits of Malacca.

As the noisy anti-government protest movement in Thailand runs out of steam, Prime Minister General Prayut Chan-ocha appears to have gained renewed confidence in his political standing. The stage is thus set for General Prayut to take a momentous decision on infrastructure development in Southern Thailand.

From Kra Canal to Khlong Thai

The idea of digging a canal across the Kra Isthmus in Southern Thailand can be traced back to the reign of King Narai the Great of the Ayutthaya kingdom. In the 17th century, Ayutthaya was a prosperous entrepôt. Traders and diplomats from Western countries, Persia and India often landed in Tanintharyi or Tenasserim on the Andaman side of the Isthmus of Kra and travelled by land to Ayutthaya. A canal across the isthmus would have enabled them to sail directly to Ayutthaya.

Unfortunately, the Siamese kingdom lost territories in Myeik or Mergui, Dawei or Tavoy, and Tanintharyi to the Burmese kingdom in 1793, during the reign of Rama I. Digging a canal between the two seas could no longer be done at the Isthmus of Kra, which had been the narrowest section of Siamese territory on the peninsula. If constructed entirely on Siamese soil, a canal would have to be dug further south, between Chumphon and Ranong - the site now being proposed for the Land Bridge.

The Kra Canal idea was resurrected during the reign of King Mongkut (1851-1868). Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French developer of the Suez Canal, travelled to Bangkok to seek permission to conduct a field survey for the canal, but King Mongkut declined his offer.

During the reign of King Chulalongkorn (1868-1910), the British, who had colonised Burma in 1824, showed some interest in the Kra Canal idea. But King Chulalongkorn turned them down for fear of exposing Siam to colonisation.

After the Second World War, an Anglo-Thai Peace Treaty was signed in Singapore on 1 January 1946. It included a specific prohibition on digging a canal across the Isthmus of Kra without permission of the British government. The treaty had little consequence, however, expiring as it did when Thailand joined the United Nations on 16 December 1946.

Numerous attempts to revive the Kra Canal idea from the 1950s to the 2000s failed to make any real progress. The only notable development came in 2004, during the administration of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, when the Senate endorsed the Route 9A, to be called the Khlong Thai. Thaksin was ousted in a coup on 19 September 2006, however, before he could take any initiative on the proposal.

Active lobbying for the Khlong Thai

Three entities have been established to promote the Khlong Thai idea: the Thai Canal Association for Study and Development (TCASD), the Thai-Chinese Commercial and Industry Trade Association (TCCITA), and the Khlong Thai Party.

The Khlong Thai Party fielded 50 candidates, running in all 14 Southern provinces in Thailand's March 2019 general elections. It failed to win any House seat, however. The candidates altogether polled only 12,946 votes, according to the Election Commission. Its election failure contradicted the claim of proponents of the project that the ambitious idea had widespread support among people in Southern Thailand.

The TCCITA is led by General Chetta Thanajaro, a former Army chief with ties to General Chavalit Yongchaiyuth, who was also a former Army chief and a former prime minister. General Chavalit was Thailand's key man in developing military-to-military cooperation between Thailand and China in opposing the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia in 1978-1989.

The TCCITA has been active in lobbying Thai senators and MPs for support of the Khlong Thai idea. Its Chinese counterpart, on the other hand, has been trying, but has so far failed, to persuade Chinese leaders to include the Khlong Thai idea in China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) master plan.

The TCASD is by far the most active among the three entities promoting the Khlong Thai. It advocates Route 9A as the most feasible. The Gulf of Thailand end of the Route 9A has space for special economic zones; in the mid-section, there is a good location for a new international airport; and on the Andaman side, there is a suitable location for an oil refinery complex, according to Taschai Inthavises, head of the TCASD's Trang Provincial Chapter.

The TCASD was officially established in 2015 and has been headed by General Pongthep Tesprateep, director of the General Prem Tinsulanonda Statesman Foundation.

In January 2020, the House of Representatives set up an ad hoc committee to study the Khlong Thai as well as the proposed Southern Economic Corridor. The committee is now headed by Maj Gen Songklod Tiprat, leader of the Thai Nation Power Party, which is one of the nine mini-parties - each with only one MP - in the 18-party government coalition. The committee and its three sub-committees have conducted hearings and field trips.

In July 2020, the committee suffered an embarrassing setback when one of its members, the environmental activist Prasitchai Noonuan, resigned in disgust. He accused the remaining committee members of "bias" in favour of the Khlong Thai idea, saying that they were more interested in finding ways and means of advancing it than in evaluating its pros and cons impartially.

Nevertheless, Maj Gen Songklod remains confident that his committee will be able to submit a substantive report to the House of Representatives in 2021.

Oil tankers bound for ports in East Asia may use the Khlong Thai because they do not need to do any shipping business in Singapore. But most other ships would still go to Singapore for trade, tourism, fuel and repairs.

Odds against the Khlong Thai

The current estimated cost of the Khlong Thai, as cited by Maj Gen Songklod, is 2,000 billion baht, or about US$66 billion. The cost will continue to rise, because of demands for higher compensation for land expropriation and the relocation of about 65,000 affected villagers. More add-ons, such as dredging longer and deeper access channels, constructing larger highway and railway bridges across the canal, and a large international airport, will only further inflate the costs.

In return, income from canal passage fees remains uncertain. It is too early to predict how shipping companies will respond to the Khlong Thai once it is in operation. The prospect of saving of just one or two days of sailing time by using the Khlong Thai may be insufficient to divert ships from the Straits of Malacca. Oil tankers bound for ports in East Asia may use the Khlong Thai because they do not need to do any shipping business in Singapore. But most other ships would still go to Singapore for trade, tourism, fuel and repairs.

Income from foreign investment in special economic zones on both ends of the Khlong Thai is also uncertain. Foreign investors now have numerous choices in Southeast Asia to set up their factories and centres for services.

Building the Khlong Thai will involve massive digging and earth-moving works. This will inevitably have a large-scale adverse environmental impact. The impact will be significant on the Andaman side, particularly at Lanta Island National Park in Krabi and Hat Chao Mai National Park in Trang. Eco-tourism has been an important source of income in Phuket, Krabi, Phang Nga, and Trang Provinces. Groups involved in the tourism sector on the Andaman coast oppose the Khlong Thai idea.

One issue that has not yet been properly examined is how the Khlong Thai will change the marine eco-systems on both ends of the proposed waterway. The water level in the Andaman Sea is usually about one metre higher than that of the Gulf of Thailand.

If Thailand owns and operates such a new international waterway in the middle of the Indo-Pacific region, it will definitely come under greater pressure from both China and the US to choose sides in the two powers' strategic rivalry.

Perhaps among the most difficult problem facing the Khlong Thai are its strategic security implications. If Thailand owns and operates such a new international waterway in the middle of the Indo-Pacific region, it will definitely come under greater pressure from both China and the US to choose sides in the two powers' strategic rivalry. Former Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva noted that the security implications of the Khlong Thai should not be overlooked, especially now that China-US rivalry in the South China Sea has intensified. In fact, the security implications prompted Deputy Prime Minister General Prawit Wongsuwan to dismiss the Khlong Thai idea as too problematic. "If it is proposed, I would insist on rejecting it", said the retired former Army chief in 2016.

General Prawit is still a deputy premier, and he has become the leader of the Phalang Pracharat Party, the largest party in the ruling coalition. It is safe to assume that General Prawit has not changed his mind about the Khlong Thai idea.

On 15 September 2020, the Prayut Cabinet approved the allocation of 68 million baht for the Ministry of Transport's Office of Transport Policy and Planning (OTPP) to fund a feasibility study of the Land Bridge...

Resurgence of the land bridge

Thailand's 20-year National Strategy, covering 2018-2037, calls for further development of the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), connecting the EEC through seamless transport infrastructure with other special economic zones in the Western and Southern regions, and enhancing Thailand's competitiveness as the regional hub for logistics and connectivity. The Land Bridge proposal fits this bill perfectly.

Its proponents count on the Land Bridge to improve Thailand's logistics performance index ranking by the World Bank, which in 2018 put Thailand at thirty-second place in the world, compared with seventh for Singapore, twelfth for Hong Kong, and twenty-seventh for Taiwan.

On 15 September 2020, the Prayut Cabinet approved the allocation of 68 million baht for the Ministry of Transport's Office of Transport Policy and Planning (OTPP) to fund a feasibility study of the Land Bridge, to conduct an environmental impact assessment, to propose a business development model, and to undertake outreach programmes to generate public understanding of the project proposal. All the studies and outreach activities are to be completed by the end of 2023 or earlier.

Supplementing the Land Bridge will be yet another mega project called the Thai Bridge, which involves a new freight route of highways and tunnels under the Gulf of Thailand to transport cargos from Chonburi Province in the EEC to either Phetburi or Prachuap Khirikhan... and onward to the port at Ranong.

Moreover, the State Railway of Thailand has been allocated 90 million baht for a field survey and a feasibility study on a dual-track railway from Chumphon to Ranong. The new railway would be linked with the China-Laos-Thailand high-speed railway running via Bangkok, Nakhon Ratchasima, Nongkhai, and Vientiane in Laos. It will also be linked to the Lat Krabang inland container depot in eastern Bangkok, as well as to dry ports under construction in four provinces.

Supplementing the Land Bridge will be yet another mega project called the Thai Bridge, which involves a new freight route of highways and tunnels under the Gulf of Thailand to transport cargos from Chonburi Province in the EEC to either Phetburi or Prachuap Khirikhan - a distance of about 90 kilometres - and onward to the port at Ranong. Its proponents may have been inspired by China's Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau bridges and expressway, which is 55 kilometres long.

The Thai Bridge project, which requires a massive investment estimated at 990 billion baht, may develop faster than the Dawei special economic zone in Myanmar, according to Deputy Prime Minister Supattanapong Punmeechaow, who leads the team of economic ministers in the Prayut administration.

However, where the Prayut administration will find money to build the Thai Bridge remains an important question. Funding the Bangkok-Nongkhai high-speed railway, which will cost 431.76 billion baht, is a higher priority for the government.

Bias for Land Bridge

Khlong Thai proponents complain that the Prayut administration has allocated too little money, just about 10 million baht, to study the project. They suspect that the Prayut administration is biased in favour of the Land Bridge.

General Prayut has maintained that both the Khlong Thai and the Land Bridge ideas remain on the table.

Investment costs [for Land Bridge] will be around 60 billion baht, or just 3 per cent of what the Khlong Thai would require.

To be sure, Transport Minister Saksiam is clearly more in favour of the Land Bridge. He included the Land Bridge among the Prayut administration's current list of mega infrastructure projects during his keynote address to the Investment 2020 seminar organised by Matichon newspaper in Bangkok on 25 September 2019.

Minister Saksiam believes that the Khlong Thai is not feasible now, in the wake of the pandemic, when funds for such a large-scale and long-term project are difficult to secure. On the other hand, he considers the Land Bridge feasible under some form of public-private partnership (PPP). Investment costs will be around 60 billion baht, or just 3 per cent of what the Khlong Thai would require.

The minister plans to develop for international tender a single PPP package which will include the four major components of the Land Bridge: deep-sea ports in Chumphon and Ranong, a dual-track railway, and a motorway running a distance of about 120 kilometres between the two ports.

According to Minister Saksiam, cargo containers from the EEC's Laem Chabang Port and Thai dry ports can be shipped to Chumphon, and unloaded onto trains or trucks which will transport them to be loaded onto ships in Ranong for onward transport overseas - especially to BIMSTEC countries. Transhipment via the Land Bridge can be done in just a few hours. This will bring some saving to Thai exporters, who have been using ports in Singapore and Malaysia for their world-wide international trade.

Ports in Singapore's Pasir Panjang and Tuas will also be likely to lose some international shipping business, especially if Chinese traders turn to use the China-Laos-Thailand railway and the Ranong port on the Land Bridge for part of their overseas shipping.

Moreover, the Land Bridge will be able to handle cargos to and from southern China using the China-Laos-Thailand high speed railway. This is one new potential advantage of the Land Bridge that the Khlong Thai lacks. Launching the Land Bridge project will create significant knock-on effects for existing ports and special economic zones in Southeast Asia. One obvious victim will be the long-delayed Dawei project, for which the Thai government seems to have diminishing political will to push.

Malaysia's East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) project, which is scheduled to be completed in 2026, will miss Thai customers who can send their cargos to the Ranong port instead of Port Klang or Tanjung Pelepas via the ECRL.

Ports in Singapore's Pasir Panjang and Tuas will also be likely to lose some international shipping business, especially if Chinese traders turn to use the China-Laos-Thailand railway and the Ranong port on the Land Bridge for part of their overseas shipping.

Land Bridge the game changer

An earlier analysis of the age-old dream of a canal across the Isthmus of Kra concluded that the ambitious idea of building the Khlong Thai looks set to remain "a distant prospect". As things stand now, the Khlong Thai will remain just an elusive idea. The new buzzword of the Prayut administration for infrastructure development in Southern Thailand is the Land Bridge.

Thailand hopes to escape from the middle-income trap to reach a higher level of prosperity and income for its people by the mid-twenty-first century. To this end, it needs a game-changing initiative to enhance its economic potential and enlarge its economic profile in the post-pandemic world. The growing stability of the Prayut administration has now put the Thai prime minister in an ideal position to make a bold and timely decision on this issue.

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2021/4 "Canals and Land Bridges: Mega-Infrastructure Proposals for Southern Thailand" by Termsak Chalermpalanupap.