China-led Mekong project terminated as Thais protest: Participatory diplomacy in action?

Thailand has terminated a China-led project on the Mekong River, following resistance by locals and conservationists. ISEAS visiting fellow Supalak Ganjanakhundee explains how this will affect the future of the Mekong River.

Thailand's cabinet agreed on 4 February 2020 to put an end to a Chinese-led project to improve the navigation channel in a segment of the Mekong River. The move followed fierce resistance by local residents and conservationists who are fearful of severe environmental and social impacts*.

Conservationists praised the Thai cabinet's decision, saying it was a "welcome development" that could signal a shift in how downstream Mekong states deal with their giant neighbour China's development ambitions. They said that it was also the culmination of decades of campaigning by those in Thailand devoted to the well-being of the Mekong, who had tirelessly raised their concerns to the authorities of the two countries over the dangers that the project posed.

Clearing the waterway of obstacles to navigation would also bring unequal benefits to the two countries. China tends to gain more than Thailand.

In light of the asymmetrical relations between the upstream Chinese colossus and its smaller downstream neighbour, Thailand, how will this decision alter the future of the Mekong River?

While scholars might come up with different terms for China's position in the international system, such as rising power or paramount power, what all of these terms have in common is an emphasis on China's superior position in dealing with countries in Southeast Asia. With differences in territory, population, economy; in military strength; in political clout; and in the role that domestic civil society plays, Thailand and China share the same goal: to utilise the Mekong for their respective economic development and mutual interest. However, the importance of the river to the two countries is not necessarily equal.

Of the 4,880 kilometres of the total length of the Mekong, 2,161 are within China, while Thailand shares 976 kilometres of the river as its natural boundary with Laos. China utilises the river much more than Thailand, as it has built a series of dams along the portion flowing through its territory, where the river is called the Lancang Jiang. While the dams mainly generate electricity for China, their reservoirs also enable China to manage water flow for different purposes including to facilitate navigation in the river. Thailand utilises the river mostly as a source of water for agriculture and for commercial navigation and tourist cruises. Clearing the waterway of obstacles to navigation would also bring unequal benefits to the two countries. China tends to gain more than Thailand.

An abundance of resources, materials and technology enables China, as a superior state, to adopt a more proactive foreign policy than Thailand, a smaller state with a narrower range of options. But that is not the end of the story, small countries, in general, can resort to multilateral cooperation, liberal values and public participation in foreign affairs in dealing with large countries.

A canalised Mekong

China's policy to use the Mekong as transportation link with its neighbours in mainland Southeast Asia dates back to the early 1990s, when Beijing saw the importance of unleashing trade and tourism in the country's southwestern region. Notably, this would mean connecting it with the regional economic dynamo, Thailand.

A joint survey on the part of China, Myanmar, Laos and Thailand undertaken in 1993, revealed the great economic potential of commercial navigation on the Mekong. It led to the Agreement on Commercial Navigation on the Lancang-Mekong River signed in April 2000.

...(the navigation channels) were to be upgraded to accommodate vessels of 500 deadweight tonnage (DWT) by 2025.

A year later, a memorandum of understanding, along with six annexes, were also finalised among the four signatories. One of those annexes included guidelines on the maintenance and improvement of the navigability of the Mekong to ensure safe and smooth passage for vessels, to allow increases in the tonnage of navigating vessels, and to reduce transportation costs. The Joint Committee on Coordination of Commercial Navigation on the Lancang-Mekong River (JCCCN) was set up in June 2001 as a multilateral mechanism for coordinating work in this area.

Beijing projected that by 2025, the transportation of goods and passengers on the Mekong would boom to a cargo volume of 6.45 million tons, and with 3.3 million passengers travelling along the river each year. Therefore, navigation on the Mekong badly needed to be improved.

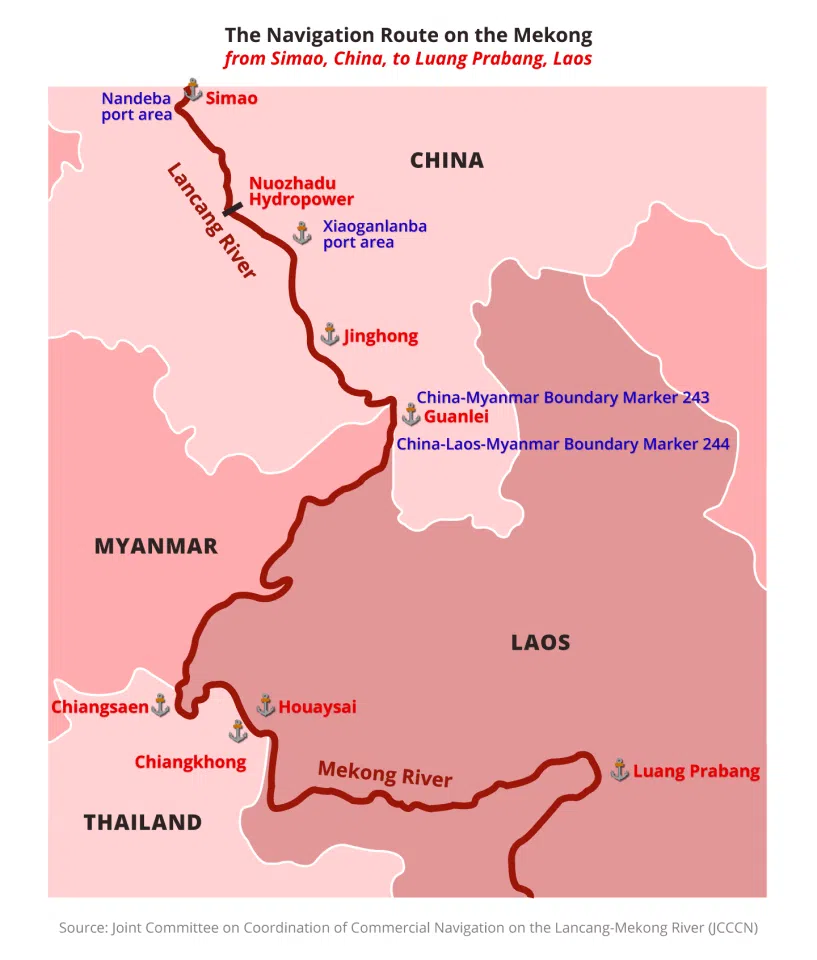

According to the agreement, the memorandum and the guidelines, both the navigation channel within China's territory from Simao Port to China-Myanmar-Laos Boundary Marker 244 and the 631-kilometre-long navigation channel from China's border to the Laotian city of Luang Prabang were to be upgraded to accommodate vessels of 500 deadweight tonnage (DWT) by 2025.

Improvement of navigation channels meant blasting to remove obstacles, including rocks, rapids, underwater shoals and other hazardous obstructions affecting navigation. Facilities to aid navigation would be installed to ensure the safety of vessels on the Mekong. To these ends, China has allocated budgetary, technological and other resources to improve the navigation channel in the Mekong not only within its territory but also outside the country since 2002. It blasted rocks and rapids to clear the waterway at 16 locations on the Mekong where it forms the China-Myanmar and Myanmar-Laos borders in 2002-2003.

Work on the lower parts of the river - notably the section between the Golden Triangle and the Laotian border town of Houaysai, opposite Thailand's Chiangkhong district - has been conducted on and off over nearly two decades. Technical problems and local resistance have slowed this work, however.

At present, the 74 kilometres of navigation channels within Chinese territory, from the port of Simao port to the Nuozhadu transport hub, can accommodate vessels of 500 DWT throughout the year, while the 185-kilometre stretch from Nuozhadu to the China-Myanmar border allows navigation by vessels of 300 DWT. Some 300 kilometres of navigation channels between the China-Myanmar border and Houaysai are able to accommodate vessels of 150 DWT throughout the year and vessels of 200-300 DWT seasonally. Another 300 kilometres of navigation channels from Houaysai to Luang Prabang have neither been improved nor seen the installation of aids to navigation. This section is navigable only for vessels of 60 DWT in the shallow dry season.

For the 96-kilometre-long section of the Mekong that forms the border between Thailand and Laos - from Chiangsaen to Chiangkhong and then Wiangkaen districts on the Thai side - Beijing made another push, starting several years ago, to continue the project with financing from the ASEAN-China Maritime Cooperation Fund. It hired its own China Communications Construction Corp (CCCC) Second Harbour Consultant Company to conduct an environmental and social impact assessment. It took a year, from April 2016 to April 2017, for the Chinese enterprise to conduct its survey. The Thai cabinet agreed on 27 December 2016 to allow Thai experts and representatives to join the process.

Thai residents along the Mekong... strongly opposed the project from the beginning

Thailand's Team Consulting Engineering and Management was also commissioned to conduct public hearings with local stakeholders including residents and conservationists. Public hearings were held seven times in the Northern Thai border province of Chiang Rai in September 2017 with a total of 811 stakeholders attending, and three times in January 2019 with a total of 513 participants. Thailand's 2017 Constitution requires such public hearings on any agreement with foreign countries which can potentially alter the country's territorial boundaries or have social and economic implications.

People's participatory diplomacy

Thai residents along the Mekong, led by the Rak Chiangkhong or "Love Chiangkhong" group and the Network of Thai People in the Eight Mekong Provinces, strongly opposed the project from the beginning on the grounds that the blasting would damage the environment, the ecological system in the river and fishery resources and that it would cause riverbank erosion and have an impact on the natural boundary line between Thailand and Laos.

Among the obstacles in 13 locations to be blasted out, they mostly highlighted the 1.6-kilometre-long section known as the Khon Pi Luang rapids, just above Chiangkhong. This section is apparently a perfect fish breeding ground. They lodged a number of petitions with Thai authorities after the December 2016 cabinet resolution to allow the blasting of the rapids, actively participated in public hearings, and submitted an open letter to Chinese President Xi Jinping expressing their concerns.

Initially, Thai authorities maintained their stance in support of improvement of the navigation channel for smooth and safe passage. They foresaw minor negative impact on the environment and the livelihoods of people along the river. The National Council for Peace and Order junta even invited the Rak Chiangkhong group to a dialogue in April 2017 to promote a better understanding of the project and to ask it not to use violent means to block the environmental assessment process when the Chinese consultant was working on the ground.

The Thai foreign ministry also took local concerns into account. Officials met with representatives of the group to listen to their concerns, starting in May 2017. The junta's Foreign Minister Don Pramudwinai raised the concerns of local stakeholders during a bilateral meeting with his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi on the sidelines of the 3rd Lancang-Mekong Cooperation ministerial meeting in Dali, China, on 15 December 2017, and hinted publicly after the meeting that the Chinese would take the Thai concerns into consideration.

China took more than a year to consider the matter and informed Thailand of its decision to drop the project when Don met Wang Yi again in Chiang Mai on 15-16 February 2019. An official statement from the Thai foreign ministry issued after the meeting said, "China noted the views from the various parties regarding the blasting of rocks and rapids in the Mekong River, which will affect the Thailand-Laos borderline and the livelihoods of the people along the river, and agreed to cooperate with the Thai side's proposal to terminate the said project."

Don also discussed the matter with Chinese officials at the provincial level when he met with Chen Hao, secretary of the Yunnan Provincial Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, on 28 March 2019. But this time, he simply thanked the Chinese for their decision to scrap the project. In response, Chen Hao reiterated that the Yunnan government's policy was to cooperate and preserve the Mekong River. In April 2019, Foreign Minister Don wrote a letter to Niwat Roikaew, the head of the Rak Chiangkhong group and the Network of Thai People in Eight Mekong Provinces to update them on his diplomatic efforts and to note that he had emphasised the importance of Mekong River as "a river that breeds and nourishes lives and the livelihood of riparian peoples and that is not a commercial river".

In making its decision to scrap the project, the Thai cabinet reasoned that the primary assessment report prepared by CCCC was not convincing...

On the multilateral front, Thai representatives to the joint working group of the quadripartite pact, expressed reservation during a meeting on 9-16 January 2019 in Wuhan, China, to the effect that the environment and social impact assessment report was far from perfect. They asked that the CCCC consultant revise it. The revised report was submitted to a meeting of the JCCCN on 26-27 March 2019 in Pattaya. That meeting turned out, in fact, to be meaningless since the decision-makers in Beijing and Bangkok had already cut a deal earlier. Nevertheless, Chinese officials informed the meeting that Beijing would no longer allocate budgetary resources for the project. The Thai delegation also notified the meeting that the foreign ministry had already asked the Chinese authorities to bring the project to a halt.

Decisive factors

In making its decision to scrap the project, the Thai cabinet reasoned that the primary assessment report prepared by CCCC was not convincing despite several rounds of revision; that local people had raised many serious concerns over the implications of the project for the environment and for their livelihoods; and, more importantly, that it had implications for the boundary line in the Mekong between Thailand and Laos. It is understandable that the blasting of underwater objects in 13 locations on the Mekong would affect the thalweg, which determines the boundary line between Thailand and Laos in accordance with 1926 Siam-Franco Treaty and the Trace de la Frontière Franco-Siamoise du Mekong map.

The two neighbours, which have had border disputes for a long time, are in the process of boundary demarcation and have agreed not to construct or make any changes within 100 metres of the boundary line delineated a century ago. Article 1 of the 2001 guidelines on navigation channel improvement made clear that work on the channel "shall not affect the natural state of the River's thalweg, the water level in downstream areas and the boundary between the countries concerned and that the environmental impact assessment to that effect has been approved". The Thai foreign ministry's Department of Treaties and Legal Affairs argued that the environmental assessment report and its model test study were not convincing in claiming that dredging and the removal of rapids and rocks underwater would not affect the thalweg.

The current state of the channels is sufficient for the volume of water transportation on the river, and an alternative route is available.

While other Thai agencies took the concerns of local residents and conservationists into consideration, the Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning raised no objection to the assessment report prepared by the Chinese consultant. It simply called for more measures to protect the environment and for compensating local residents for possible damages.

There has been no further discussion on the future of the project since the Thai cabinet resolution of 4 February, and clearance of navigation channels in the Mekong would in any case not serve Thailand's interests. The current state of the channels is sufficient for the volume of water transportation on the river, and an alternative route is available.

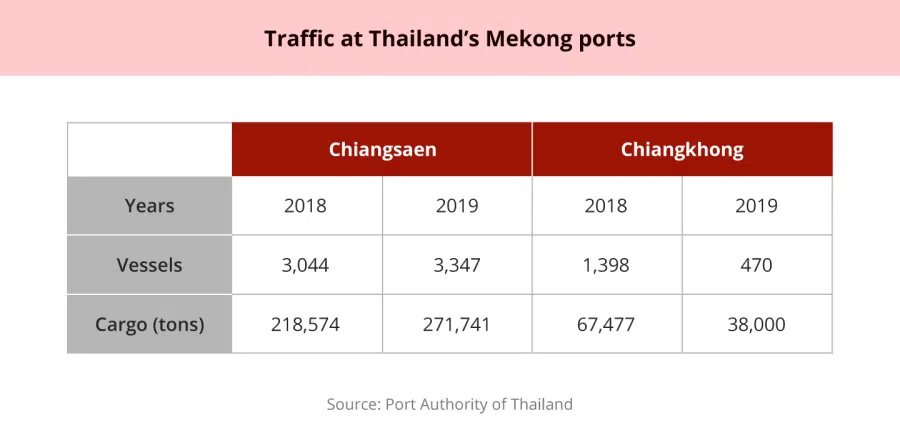

Traffic on the Mekong has not always increased according to predictions. Thailand's Chiangsaen and Chiangkhong ports received altogether 3,817 vessels, mostly Chinese, in 2019 - down from 4,442 vessels in 2018. More importantly, Thailand is keen on land transport, with a bridge across the Mekong connecting Chiangkhong and Houaysai having been completed in 2013. Transport is more convenient along the 1,100-kilometre-route from the Thai via Laos' R3 Highway to Kunming in China's Yunnan Province. In the meantime, the US$6 billion railway project linking the China-Laos border to Vientiane via Luang Prabang is due for completion in 2021. That will offer still more alternatives for transportation in the Mekong sub-region.

Conclusion

Thailand's decision to scrap the clearing of navigation channels in the Mekong reflects a new dimension both in the country's relations with China and in Thai diplomacy. Beijing has adopted an approach to the countries downstream on the Mekong centred on the idea of its "peaceful rise" and on being a good neighbour. It has sought cooperation rather than conflict with the smaller states downriver. While economic development is the key element in China's foreign policy, the country has shown flexibility in policy implementation. It was not necessary for Beijing to push ahead with the project to clear navigation channels on the Mekong at the risk of possible conflict with people downstream; that river is after all not the only way for China to reach Southeast Asia.

Judging from the Thai foreign ministry's moves in recent years, Thailand seems to have learned how to take people's participation into account in its foreign policy and diplomacy. The government's concern over the implications of the proposed project for the international boundary on its own might not have been sufficient to convince Beijing to end the project, if not for the voices of local people in the two countries' diplomatic engagement. While the current Thai government has its roots in a military coup and embeds many illiberal values in its policies, it was nevertheless able to use public participation effectively to engage with a large country like China.

However, several other observations merit attention. First, China might not have decided to be so flexible if it had had more interest in the project and if the Mekong had been its only gateway to Southeast Asia. After all, Beijing has more bargaining power and influence than its small neighbours. Second, China has already utilised the Mekong much more than other countries. It is not necessary to mention that the environmental and ecological system of the Mekong has already been affected by other development projects and by waterway clearance upstream. There is no comprehensive scientific study of that impact. Thailand, therefore, continues to use environmental and social considerations in engaging China over the Mekong.

Note:

*The cabinet resolution indicated that the 20-year-old project was no longer receiving financial backing from the ASEAN-China Maritime Cooperation Fund, and "therefore the project has been ceased. There will be no continuation of the project unless member countries agree [to push forward] via diplomatic channels to continue."

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2020/30 "Thailand Uses Participatory Diplomacy to Terminate the Joint Clearing of the Mekong with China".

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)