Americans should not oversimplify China into a few sensitive issues

Whether Pew or Gallup, poll results show that most Americans have long held a consistent negative impression of China. These sentiments have cooled even more over the past few years. The Strategic Competition Act of 2021 passed by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee is a sign that this trend is getting increasingly legalised.

The latest Pew survey shows that as much as 69% of Americans aged 50 and above supported limits on Chinese students in the US; half of the respondents aged 30-49 supported the move, while only 31% of those aged 18-29 supported it. In terms of academic qualifications, more than half of respondents with college degrees objected to imposing limits, while the opposite was true of those with no college degrees. This shows that the younger generation of Americans are more liberal-minded than the previous generation, especially after receiving higher education, and they are less likely to be biased against China and Chinese students.

In my role as a history researcher and educator who teaches in English in the US, I aim to guide American students to read deeply into social science, think critically and form a fairer and more balanced view of the world. Under the current situation - when the pandemic has had a significant impact on economic models and lifestyles around the world, and China is undergoing deep social and economic reforms - how a China-born academic tells the story of modern China in the classroom is something worth thinking about.

Once, at a public forum that I attended, a colleague - a retired professor of Japanese descent - even encouraged students to discuss how to attack military facilities within China...

How American undergraduates see China

In my experience, American undergraduates' ideas of China are usually influenced by their parents, the media, and the cultural environment even before they go to college, and there is a wide spectrum of views. On the one hand, some college students - due to the open environment in college coupled with the curiosity of youth - are also likely to feel friendliness or an inclination towards China. On the other hand, the general social climate, as well as the media, would inevitably lead many US students to be judgemental about China.

In the course of teaching and writing, some of my American colleagues habitually guide their students to follow some sensitive topics that they themselves are interested in, such as China's so-called coercive diplomacy, Tibet, and Xinjiang, which has also led to students' tendency to be judgemental.

Once, at a public forum that I attended, a colleague - a retired professor of Japanese descent - even encouraged students to discuss how to attack military facilities within China, which saw active participation from several students. This actually went against academic neutrality; it was done intentionally to stir hostility among the American students.

Another American colleague, an admirer of the Dalai Lama, encouraged students to study the Tibet issue, and invited a group to hold a Tibetan "art exhibition" in the school. This group had clear political demands, and displayed associated logos, banners, and images; there was strong backlash from some Chinese students.

In my view, the choice of research topics is open. However, for American students who have no real grasp of Chinese and can only read English-language materials, jumping into this highly politicised topic abruptly means that they can only be guided by the inherent prejudices of the English-speaking world.

Some Chinese colleagues have also joined in, adding to the trend of going against the neutrality of values. In planning a course, a former colleague from China set out his course objective as getting American students to learn to "cope with" China. But even in English, to "cope with" means "to deal with and attempt to overcome problems and difficulties". The obvious negative and confrontational meaning of the term also had an American colleague feeling that it was inappropriate.

American students need to learn and understand that China, like the US, also has its own cultural heritage, historical background, and modernisation process.

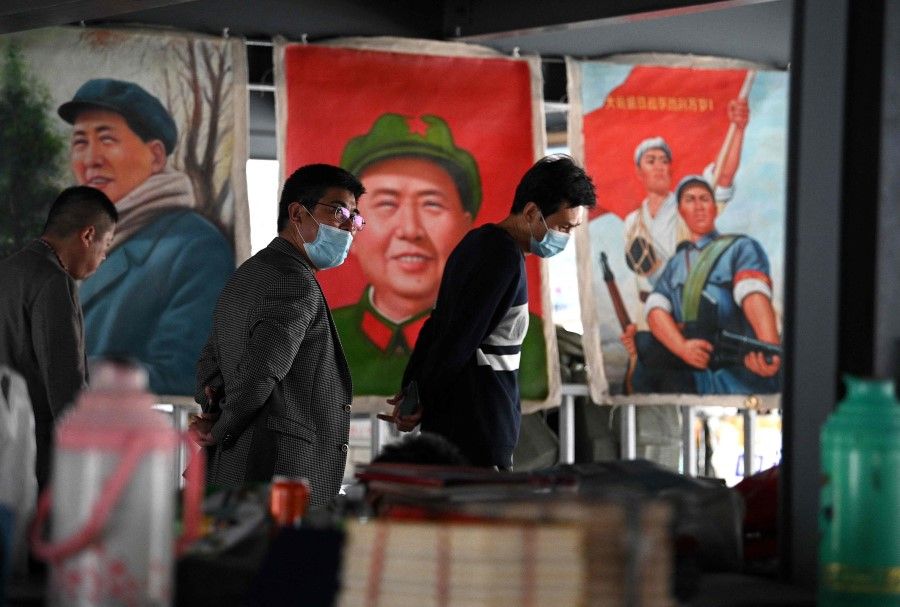

After years of advising undergraduates in their papers and theses, I feel that American students are more likely to feel positive about ancient Chinese culture and historical figures. Almost routinely, each term there are students who show a deep interest in the practice of foot-binding. But when it comes to modern-day issues, students tend to judge China harshly; however, there are also students who have balanced or even admiring views of China. Of the theses I have advised, some students have explored women's roles in modern Chinese cinema, or the black market and underground trade during the time of Mao Zedong, or the history of Chinese characters, or environmental issues in ancient China. A significant proportion research on Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution.

Some non-history majors who also do not read China studies usually choose a course on China for academic credits in their last term before graduation. An American student majoring in political studies previously took a course by the abovementioned Japanese academic with a hostile attitude towards China, which was focused on the US point of view. However, he hoped to get another perspective from my course on modern Chinese history. A second American political science student had never taken any China-focused course, but was curious and wanted to get some understanding of China before graduating. A second-generation US-born Chinese economics student wanted to take a course that would give him an idea of the China of his father's generation. These various reasons show that a significant number of American students want to gain a deeper knowledge and a different perspective of China through their classes, especially when the instructor is of Chinese descent.

American students need to learn and understand that China, like the US, also has its own cultural heritage, historical background, and modernisation process. And when it comes to issues close to their hearts such as conservation, gender equality, and LGBT rights, the US like other countries has gone through a dynamic process of conflict and improvement. Likewise, China faces a structural conflict between development and conservation, as well as rethinking and shifting of gender perceptions along with greater tolerance, all of which is happening globally.

American students should see China's efforts and achievements in conservation; the fact is, pollution was also a serious problem while America was industrialising. Today's American college students do not think about the unlimited use of plastic bags in US supermarkets, and know nothing about the various measures taken by East Asian countries to limit the use of plastics, and are surprised when I mention it.

A domestic perspective

My pedagogy is that of a historicist, and my method is one of rigorous academic writing. In the epistemological sense, I resist the approach of the US media and object to preconceived notions and to simply assessing modern China by US standards. I get students to gain sufficient knowledge of China's historical situation and engage in in-depth reading and discussion of academic research, in order to examine specific policies and beliefs, as well as the aims, processes, and consequences of specific events.

For example, how the Chinese revolution began and the place it holds in modern memory, as well as China's century of industrialisation amid war and unrest and scarce capital, are all learning topics - I previously researched the history of shipping in the late Qing dynasty, and visited a commemorative museum in Beibei, Chongqing, dedicated to shipping magnate Lu Zuofu, so I do feel quite strongly about that particular topic.

The over-politicised emphasis on sensitive topics should shift to practical governance.

Besides that, seeing and hearing from ordinary Chinese themselves provide for a more complete understanding of China from the inside. English-language academic works that talk about the urban-rural divide, as well as research into intellectuals - whose social status is far more prominent in China than in the US - and relevant frameworks of analysis, can also be brought into pedagogy.

As a developing country, China is still urbanising and resolving rural poverty, and pursuing prosperity, which is a social shift that is full of contradictions and conflict. Urbanisation, farming folk who go to cities to work, rural industrialisation and commercialisation and the corporatisation of the governance model, the long process of shifting systems, gender issues and changes in gender relations, rural poverty alleviation, changes in village culture, reforms in village healthcare systems, the marketisation of traditional folk art, rural tourism - all of these should be included in learning and research. The over-politicised emphasis on sensitive topics should shift to practical governance.

In 2019, on a study trip to a Miao minority village called Xijiang in Guizhou, I noticed that the investors and developers from Zhejiang and the local villagers interacted and cooperated in a very interesting way. Visitors from Zhejiang entered Xijiang for free, and local villagers also rode for free on electric vehicles, which were in turn different from the vehicles that regular visitors had to purchase tickets to ride. At the same time, investors and the villagers were also negotiating the rights to the village inn. On the one hand, open tourism enlivened the previously quiet village; on the other hand, the Miao people who used to go out and work chose to return because of the job opportunities at their doorstep. This growth model and the interactions, developments, and tussles within cannot be described with the contrasting terms of "oppression vs resistance" that some Americans are accustomed to using when looking at China.

Perhaps we can learn from sociologists Qu Jingdong of Peking University and Ying Xing of the China University of Political Science and Law. Qu says there are two main themes in sociology - first, how we live; second, rapid changes and intense conflict in society, and even the effects of sudden changes on politics, society, culture, religion, and people. Ying notes that we should look at China's social changes more from the perspective of someone within China.

As for students who are bent on researching the coercive diplomacy of modern China, I guide them to understand China's Confucian-based diplomatic principles, and its historical relations with the nomadic rulers to the north of China, and with coastal states to its east and south, and modern China is in fact in a fragile and defensive position in international relations. I also remind them to take note of inherent biases in many research papers. The truth is, some American academics have mistaken ideas about the South China Sea issue, and only talk generically about it. And since the 1930s, neither the Nationalist government nor the PRC government has ever said the South China Sea belongs to China; it has only claimed sovereignty over some islands and the waters around them.

In today's America, a more meaningful form of critical thinking is American students reflecting on US politicians and media that control the narrative, and getting to know the world again, and seeing how limited information sources and perspectives are for Americans.

What is the kind of critical thinking that American students need?

American students live in an open society, but the perspective of this open society is often limited by the American-centric views that Americans have. For an academic of Chinese descent who teaches Chinese history and modern affairs, as American mainstream media keeps reporting negatively about what is happening in China, and the fight against the pandemic sparks more debate about the principles and models of Asian and Western governance, the meaning of critical thinking in the American classroom is not to get in line with standard, trite Western stereotypes, or to endlessly "criticise" China on sensitive political issues, or to create fear. That would be no different from following the crowd; there would be no real conscious assessment.

In today's America, a more meaningful form of critical thinking is American students reflecting on US politicians and media that control the narrative, and getting to know the world again, and seeing how limited information sources and perspectives are for Americans. As for critical thinking in terms of mainstream media and narratives, fairer writings on China's recent developments; a deeper understanding of the changes happening in China now; post-pandemic analyses of the public health models in China and other countries and regions such as India, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan and how they handled the pandemic; and rational reflections on global narratives on the relationships between individuals and groups, freedom and restrictions, autonomy and governance, country and community, country and country - all this will help to remove the mystique of China for the young generation of Americans and reduce their dependence on homogenous reports on particular news incidents, so that they give more serious thought to societies outside of the US and how they have developed and improved, and how they are governed.

The fact is, the social sciences arena - dominated by white Americans - is generally uninterested in the situation of minority Asian Americans. Most academics who research overseas Asian history and current affairs are overseas Asians themselves. However, they are particularly passionate about minority issues within China, and take an especially "sympathetic" stance, which also calls for critical reflection. Paradoxically, some Western academics use constructivist theory, taking a nihilist approach to the history of some minorities, such as claiming that the Zhuang people were created, and the Miao people were invented. This has also stirred strong distaste among academics of these minority groups - when I went back to China to conduct interviews, I witnessed a minority academic loudly criticising the "research" of an American academic.

Americans should not oversimplify China into a few sensitive issues, and a target to be attacked and "dealt with"; they should consider China something to be understood as an equal.

I also have my doubts about how American professors like to use in their classes personal "memoirs" by Chinese people who take a (to me) trite approach of "Chinese suffering, Western salvation". I have stopped using these in my own classes, replacing them with academic research papers and writings.

There is no doubt that Americans lack sufficient knowledge about the struggles of modern Chinese. Telling the China story has inevitably become a part of teaching that in fact cannot be completely separated from one's stand, attitude, perspective, and background, especially in subjects such as politics, history, and economics. Americans should not oversimplify China into a few sensitive issues, and a target to be attacked and "dealt with"; they should consider China something to be understood as an equal. As an American academic said in an email to me: "American students (learn in their terrible social studies classes) that everything is about bias, and when it comes to China, everything is already immediately always repressive."

First-generation overseas Chinese academics have lived amid two cultures and communities. Their mother tongue is Chinese, and they are more able to handle research findings in Chinese from within China. They can better understand the media, internet, and life in China, while doing research work mainly in English. They have a broader international perspective, and generally have richer life experiences than the average American academic. They can really provide a perspective that is different from most Western academics. Through interpretation, they can guide and influence students to deepen their understanding and subsequent evaluation of China. Students would also look forward to this sort of fair-minded, serious narrative, with a deeper historical and comparative perspective.