Beautiful or outdated? The journey of Chinese characters through the ages

With language and words as its building blocks, literature is a means to express one's inner emotions, the vicissitudes of life, the wonders of the Universe, the relationship between God and Man, the cruelty of war and the comfort of peace. Mountains and rivers, fauna and flora, separations and reunions, joys and sorrows can all be described in words. Yet, there is a process of transformation and elevation from mere words to literature, and the key factor in this transformation lies in the use of words. Only after mastering the intricacies of the written word can one's imagination be set free to go beyond language's most basic function of communication.

A work of art embodies both form and substance. The latter is all around us; although people differ in their sensitivity to life's experiences and happenings, everybody experiences them. Form, on the other hand, is difficult to master. Humans fill the earth, but few become artists. Those who can read and write are many, but few are able to artistically turn works, as if by magic, into immortal works of literature.

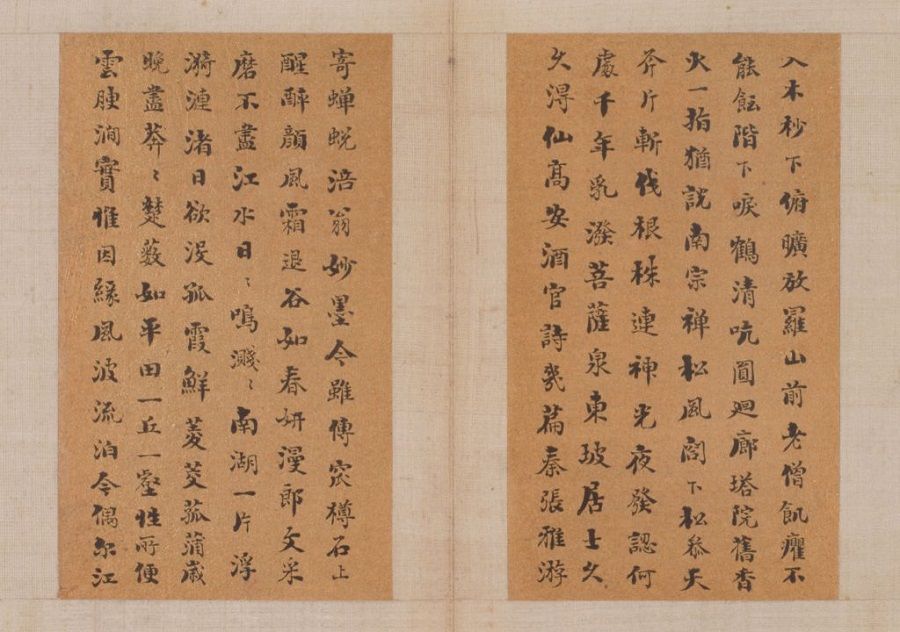

Jean-Paul Sartre's What is Literature? considers poetry to be at the apex of literature: "The empire of signs is prose; poetry is on the side of painting, sculpture, and music... Poets are men who refuse to utilise language... Once and for all he has chosen the poetic attitude which considers words as things and not as signs... But if he dwells upon words, as does the painter with colours and the musician with sounds, that does not mean that they have lost all meaning in his eyes. Indeed, it is meaning alone which can give words their verbal unity. Without it they are frittered away into sounds and strokes of the pen. Only, it too becomes natural."

Although Sartre was not talking about the relationship between Chinese characters and poetry, this excerpt describing a poet's train of thought while composing poems is especially apt for discussing the Chinese poet's creative process, and highlighting the characteristics of Chinese characters.

China boasts of vast lands, a huge population and a long history. The source and foundation of Chinese literature is a culmination of its culture and writing traditions. The strong vitality of Chinese characters comes from history and culture, from the life records of hundreds of millions of Chinese people, and from the painstaking works of writers.The Chinese have been using these unique square-shaped Chinese characters for 4000 years; such a mode of writing stands in interesting contrast to the alphabet-based languages used by other civilisations.

Chinese characters are not phonetic - sight, images, and sound work in tandem with one another, complementing and influencing one another. The relationship between language and words is rather complex - not only does it affect literary arts, it also influences the way we think. Neurologists who study human memory have already discovered that using alphabetical languages affects a certain portion of the brain that is related to auditory memory. Using Chinese characters, however, not only affects the part of the brain that is related to auditory memory, but also affects the portion of the brain related to visual memory.

The uniqueness of Chinese character writing means that there is substantial room for manoeuvre between Chinese characters and language in the interplay between visual and auditory thinking. Compared with alphabetical languages, Chinese characters are not only a direct translation of language, but also a reflection of the individual legacies and interactions between the forms, meanings, and sounds of the characters in different contexts. These make Chinese characters rich and colourful, and also affects the development of Chinese literature.

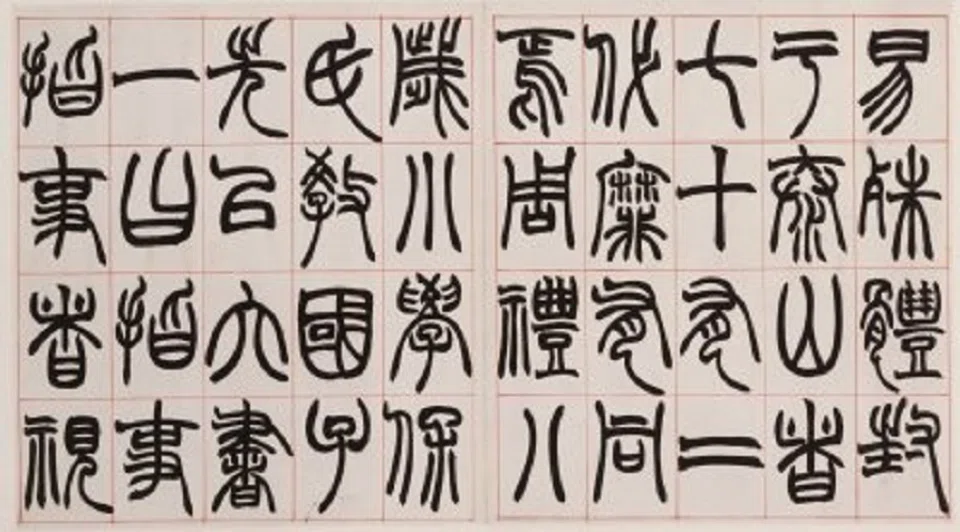

Chinese characters have also undergone a 2000-years evolutionary process from its origins until its present established state. Some archaic characters are even too elusive and profound for Xu Shen, the great philologist of the Eastern Han dynasty, to comprehend.

Xu classified Chinese characters into six types in Shuo Wen Jie Zi (《说文解字》, a Chinese dictionary of the early second century), and had even termed "止戈为武" (zhi ge wei wu, meaning that the word wu (武, martial) is made up of the words zhi (止, stop) and ge (戈, war), implying that the highest form of martial arts is in the ability to stop a war) as the classic example of a compound ideograph (会意字, compounds of two or more pictographic or ideographic characters to suggest the meaning of the word to be represented).

After the oracle bone script of the word was discovered, we finally realised that the original meaning of wu is "荷戈步武" (he ge bu wu) instead, which actually means "to go to war".

We also realised that there was actually a complicated historical process behind "天雨粟鬼夜哭"*, the saying that refers to humans unlocking their full potential after the discovery of Chinese characters. Just like infants who cry at night and would continue to cry into adulthood as life continues to throw challenges at them, the heavens may bless them with a windfall, but could also curse them with a movement to abolish Chinese characters - to which they cannot help but cry.

After Qin Shi Huang standardised writing, the square shapes of Chinese characters are more or less fixed, but its semantics are transformed through changes in human understanding. Thus, it is not true that the physiognomy of Chinese characters is unchanging. The complete stabilisation of the form of Chinese characters is probably due to the invention of printing, which explains why the regular script is still used today.

It is indeed peculiar and rare in the history of human civilisation for the form of Chinese characters to remain relatively similar over a period of 2000 years. However, whether this is seen as unique and extraordinary is a different matter altogether.

The elites of the May Fourth movement, for one, disagree - just like the representatives of the pan-democracy camp in Hong Kong who would disagree - with everything China-related to create a better future for themselves. They believe that the uniqueness of Chinese characters stems from the entrenched bad habits of the primitive people and is especially outdated, hindering the development of science and democracy. As Lu Xun once said, "If Chinese characters are not destroyed, then China will die" (汉字不灭,中国必亡). Along with many other intense cultural advancements ideologies, he was a strong advocate of romanising Chinese characters.

Mao Zedong was famous for his ideology of "overcorrection" (矫枉必须过正), or wanting to completely eliminate the old institution and old culture. Yet, out of personal preference and his love of classics and Chinese characters, he did not insist on abolishing Chinese characters.

It is such a great relief that we're still able to write literature in Chinese characters, and read Classic of Poetry (诗经), Chu Ci (楚辞), Tang poetry (唐诗), and Song Ci (宋词) that were distributed and printed in Chinese, today!

Note:

*Legend has it that after Cang Jie created Chinese characters, grains fell from the heavens like rain, and ghosts cried at night. This symbolised that the Chinese civilisation had unlocked its potential and would become more intelligent and creative with the discovery of words. Thus, ghosts no longer had control over their destinies and could only helplessly cry at night.