China's 5G ambitions undiminished by pandemic and sanctions

President Xi Jinping has long been an advocate for the move to a digital economy in China, and a large number of policies introduced during his tenure have reflected this goal. The 14th Five-Year Plan adopted in 2021 thus represents the Chinese leadership's capstone framework for the transition to a digital economy in China by 2025. Table 1 indicates the highlights of these ambitious goals.

Launching 5G: the 'infrastructure first' syndrome

In January 2022, the State Council provided guidelines for the construction of the fifth generation (5G) mobile communications infrastructure together with a national-level, integrated big data system. Since 2019, Chinese mobile telecommunications operators have rolled out the 5G mobile communications network, which is anticipated to include 2 million 5G base stations by the end of 2022, covering most of China.

It has been estimated that Chinese mobile operators will invest nearly US$210 billion in their networks between 2020 and 2025, of which 90% will be dedicated to 5G. The Chinese market for 4G smartphones reached saturation in 2019, and the launch of 5G services offers an opportunity for telco service providers to persuade customers to upgrade their mobiles.

Apple was among the first to introduce its 5G-enabled phone in China, but domestic smartphone producers quickly caught up, accounting for 86.6% of mobile phone shipments in 2021. In May 2022, a total of 899.3 million 5G subscriptions had been signed up with Chinese mobile operators, and the number of 5G users appear poised to increase further in the future.

However, China still faces a shortage of new and exciting 5G applications to drive consumer uptake of new services as well as profitable industrial applications.

However, China still faces a shortage of new and exciting 5G applications to drive consumer uptake of new services as well as profitable industrial applications. The lag experienced in developing commercially profitable applications for consumers using 5G services reflects a typical Chinese top-down policy failure, what one Chinese expert has called the "infrastructure first" syndrome, namely, "building a road and waiting for the cars to arrive".

5G services and Covid-19

The outbreak of Covid-19 in China in 2019 became an important juncture for the use of digital technologies and 5G to launch new applications for disease prevention and control. Initially, local governments relied on health codes developed by Alipay and WeChat in order to identify people potentially exposed to Covid-19.

With the availability of more advanced 5G services, however, wearable devices have been used for Covid-19 control, for instance, to measure the health status of potentially infected people and self-detect physiological changes during isolation. 5G-powered infrared thermal imaging temperature measuring equipment has also been utilised to detect body temperature at a distance of 10 metres and implement face tracking. Recently, Beijing residents returning from domestic travel were asked to wear Covid-19 monitoring bracelets, causing a debate on social media that was later removed by the authorities.

Covid-19 has also had some impact on the production and deployment of 5G systems

On the other hand, the 5G infrastructure has helped China launch new telemedicine and healthcare services such as remote diagnosis and consultation through a combination of advanced communication and artificial intelligence, even trying out remote CT scanning and remote ultrasound testing. Advanced telecommunications have also been essential for providing e-commerce and logistics solutions for people who were quarantined or isolated in their homes, and for delivering on-line education to students.

Of course, Covid-19 has also had some impact on the production and deployment of 5G systems, because the lockdowns caused by China's zero-Covid strategy have upset global value chains and production in China generally.

An issue that leading equipment vendors like Huawei or operators such as China Mobile have encountered in practice is their lack of domain knowledge and specialised technical competence for specific industrial or service sectors.

Modernising industries with the Internet of Things

The 5G equipment producers and service operators have been particularly eager to develop Internet of Things (IoT) applications for industry, mining and services, and have adopted new alliances to promote R&D and testing for such software. But so far, many of the applications that mobile vendors have installed have generally been "showroom-only" systems that have little commercial potential in the Chinese economy.

An issue that leading equipment vendors like Huawei or operators such as China Mobile have encountered in practice is their lack of domain knowledge and specialised technical competence for specific industrial or service sectors. Service operators have also discovered that their conventional approaches to delivering and charging products - such as charging customers on the basis of the amount of data traffic - often have to be adapted to the specific sector or industry segment.

Nevertheless, a successful experience in adoption of 5G based networks was gained by the electric power grid operators in China. The electricity grid has expanded very fast in China during the last decade as the demand for energy grew by leaps and bounds and the network was upgraded to tap new sources of renewable energy such as power generated by wind turbines in remote areas of China.

In order to handle maintenance and distribution, the Chinese grid operators have collaborated with 5G vendors to develop "edge computing" facilities, that is, distributed computing that brings computation and data storage closer to the sources of data. This has allowed them to develop new innovative technologies in the edge computing field, with the largest number of patents in the field globally.

The economic benefits of 5G infrastructure could be substantial for consumers, once advanced 5G apps for virtual reality, etc. become widely available. However, the largest benefits from 5G for China is likely to happen with the diffusion of industrial automation, logistic services, autonomous vehicle control, and other commercial products facilitated by the 5G infrastructure.

Overseas expansion along the Digital Silk Road

On the international front, China has encountered several setbacks that challenge both the domestic and international expansion of the digital economy. Based on issues of national security, the US and allied countries have effectively banned Huawei and ZTE in their systems, and countries covered in the Digital Silk Road initiative have been under pressure to follow suit.

Although authorities in the US and Europe were concerned with the same security issues arising from the emerging 5G networks, their approaches were different in significant respects. The US opted for an explicit ban on Chinese vendors, while European countries sought to achieve similar security for their 5G networks by means of legal-political regulation that made it unlikely that Chinese companies would become major suppliers.

Chinese digital expansion in Southeast Asia has encountered mixed experiences.

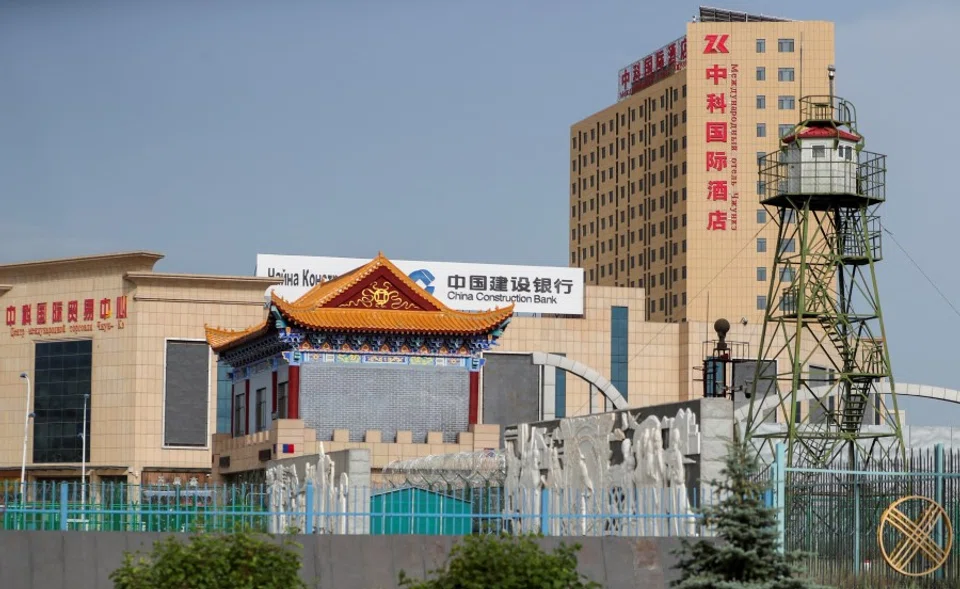

The supply of digital infrastructure such as 5G, data centres and surveillance equipment has been an important component of the Digital Silk Road. In Central Asia, China's 5G investments in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan are turning into a major digital infrastructure engagement, led by Huawei.

Central Asia is also developing its surveillance capacity by cooperating with Chinese ICT companies to create "Safe City projects". Safe City projects use facial recognition cameras, data management systems and control centres to monitor the activity of citizens and levy fines.

Chinese digital expansion in Southeast Asia has encountered mixed experiences. Thailand has been one of the enthusiastic recipients of advanced 5G systems from Huawei and aims to be among the first countries in the region to establish 5G networks and cloud computing data centres.

Singapore has developed its mobile networks and a broad range of digital services together with Chinese companies, and has been engaged in digital development projects in China. However, when it came to construction of the 5G networks, the country allocated most 5G spectrum resources to corporations with Ericsson and Nokia as suppliers, while an operator collaborating with Huawei received a minor share of spectrum resources.

'Choke points' in the US-China tech war

The US-China trade war that was initiated by Trump has quickly transformed into a conflict of technology leadership, and in the process the US has threatened to reduce Chinese access to semiconductor microchips and equipment essential for the expansion of 5G infrastructure and artificial intelligence systems.

In this conflict, the main US weapon has been the notorious Entity List that the US Department of Commerce Bureau of Industry and Security employs to restrict the export, re-export and in-country transfer of US produced items to entities - individuals, organisations and/or companies - believed to be involved in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the US.

Currently, 468 Chinese firms are listed on the Entity List, with Huawei and its affiliates in China listed 57 times, together with a large number of overseas affiliates. During 2019 and 2020, many firms in surveillance and technology, primarily companies that specialise in artificial intelligence, facial recognition and integrated circuits, were added to the Entity List.

Given that the Chinese high-tech firms depend to a large extent on import of advanced microelectronic components, these restrictions are perceived in China as "choke points" - sanctions in the form of bottlenecks in the global value chains that are designed to hurt the country's development.

... US semiconductor related companies could lose 8% of their global market share and 16% of their revenues in 2020, given the restrictions enacted with the current Entity List - ultimately ending the US leadership in semiconductors.

China's reaction to this challenge has predictably been to intensify policy measures and direct support to the establishment of technological capabilities and production facilities in the sanctioned high technology sectors.

China has also retaliated by creating its own "Unreliable Entity List" in September 2020 and an Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law in June 2021 that provides legal grounds for Chinese government authorities and private individuals and entities to take countermeasures against "discriminatory restrictive" foreign sanctions. However, so far, no announcement has been made regarding foreign firms that have been affected by the Unreliable Entities List.

How to shoot yourself in the foot

While Chinese actions have prepared the ground for extensive "tit for tat" reciprocal sanctions on US multinational firms and high technology sectors such as semiconductors, they have not been implemented on a major scale. However, the US high-tech industries may actually already be adversely affected by their government's actions.

It appears that a reluctant US semiconductor industry was forced into implementing export restrictions targeting the semiconductor supply chain in order to constrain Huawei. It has been estimated that US semiconductor related companies could lose 8% of their global market share and 16% of their revenues in 2020, given the restrictions enacted with the current Entity List - ultimately ending the US leadership in semiconductors.

A decoupling between the US and China for telecommunications, semiconductors and other advanced technology sectors would therefore present great challenges to China's plans for rapid expansion of 5G infrastructure. In the meantime, it is likely that a major decoupling will not dampen China's ambitions - rather, it would amplify them - while breaking up the current interconnected technology supply chains between the two countries could have negative effects on US technological leadership.

This article draws on material that was first published as an East Asian Institute Background Brief.