Is China's public discourse becoming polarised?

The current political spectrum in China, explained in one diagram - scroll down for more.

In June 2019, the Hong Kong academic journal The Twenty-First Century published an article entitled "The Major Challenge to the Chinese Regime Today", in which well-known Chinese sociologist Zhao Dingxin analysed the political shift of China's public opinion in recent years. He noted that the polarisation that has surfaced since 2014 poses a threat to China's domestic political stability, a proposition that was criticised by a young political scientist Lin Meng, who found Zhao's framework of analysis "outdated" and clearly not applicable to today's China. This raises the question: how do we define China's political spectrum?

In his article, Zhao used the traditional left/right dichotomy, with Marxists and nationalists on the left and liberalists (as defined in the context of China) on the right. Indeed, this would have been representative of China's political sentiment a decade ago. In 2008, China expert Joseph Fewsmith released a revised edition of his book China Since Tiananmen, in which China's intellectuals were divided along a political spectrum as the "New Left" and the "liberals". However, in recent years, there have been changes and shifts in political thinking, and this division becomes less and less applicable. But before discussing an appropriate Chinese framework, it is useful to briefly examine the evolution of the political spectrum in the West.

The political spectrum in the West

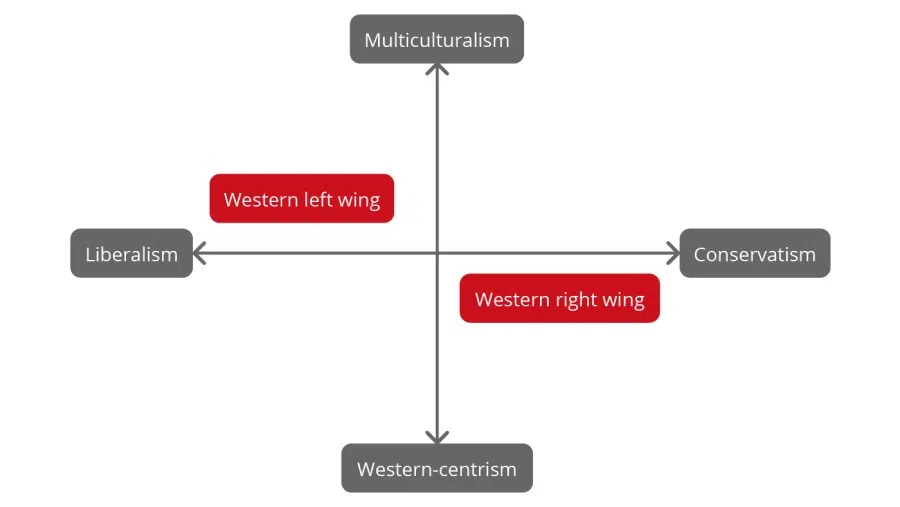

Identity politics brought a new cultural dimension to the political spectrum in the West, with cultural diversity demonstrating the new left-wing and Western-centrism serving as the new right-wing.

After the Industrial Revolution, modern societies moved towards liberalism and socialism, while conservatism held its place as an antithesis. For this reason, political textbooks in the West generally rendered the political spectrum as a straight line with liberalism in the centre, socialism on the left, and conservatism on the right. From the French Revolution to the 1950s, it was understood that the main difference between these three schools of thought was their attitude towards equality and freedom. In general, the further left a regime was on the spectrum, the more it advocated equality and change, while the right valued freedom and tradition.

After the 1960s, Europe and the US went through social movements pushed by the New Left, such as the May 1968 unrest, the Civil Rights Movement, and the 1960s counterculture movement. These movements drove the rise of the Western identity politics that still exist today. Identity politics brought a new cultural dimension to the political spectrum in the West, with cultural diversity demonstrating the new left-wing and Western-centrism serving as the new right-wing.

For the past few decades, one focal point of contention in the US and Europe has been mainstream acceptance of minority identity in gender, race, and religion. The 2018 book Identity, by US political scientist Francis Fukuyama, is an analysis and assessment of identity politics. In his view, identity politics challenges the rational universalism of Western countries, while also spurring the spread of right-wing populism.

Figure 1 shows a two-dimensional Western political spectrum. The horizontal axis represents the traditional economic dimension of equality/freedom, while the vertical axis represents the new cultural dimension of multiculturalism/conservatism. It should be noted that Western liberalism continued to shift leftwards during the 20th century, almost approaching social democratic thinking, while conservatism also shifted to commit to classic liberalism. In Figure 1, the Western left is located in the top left corner. It aims for economic equality and cultural diversity. The right wing, situated at the bottom right, holds the opposite position from those of the left, in terms of both culture and economy. Following Brexit and Trump's election, this right-left confrontation has grown more polarised.

The way of Chinese politics

In analysing the range of Chinese politics, identity politics cannot be viewed as a dimension on its own.

Given China's strict control over the cultural sphere, any movement in identity politics is limited. Though the #metoo movement has sparked a storm of discussion and there is a growing number of "out" LGBT individuals, the political influence of such shifts in China is not comparable to that seen in the West. The major demands of China's left focus on economic issues, such as reducing the income gap and increasing social assistance. In analysing the range of Chinese politics, identity politics cannot be viewed as a dimension on its own.

The China model appeals to those on both the left and right who are dissatisfied with Western democracy, though it is often criticised by liberals inside the country.

In the Western political context, while the tussle between the left and right is intensifying, both sides generally agree on the democratic system of their respective countries. However, the way the political system is designed and operates has been one of the core questions for debate between China's left and right. For a period after the Cold War, Chinese authorities were defensive about their political system. Liberal intellectuals and much of the public saw democratisation as the mainstream of world civilisation, and they believed that it was only a matter of time before China would adopt a democratic system. However, over the past decade, with the political and economic crises in the West and China's continued growth, democracy has lost its shine for many Chinese, and the "China model" has become an alternative solution to the Western democratic system.

While academics still debate the definition of the China Model, the general emphasis is on the concentration of power and the indirect election of national leaders. Deng Xiaoping said in the 1980s, "The advantage of China's socialism over capitalism is that it gets the entire country on the same page, where power is focused and priorities are assured." The China model appeals to those on both the left and right who are dissatisfied with Western democracy, though it is often criticised by liberals inside the country. Alongside the traditional lens of economics, it is useful to view this governance model as another perspective from which to analyse China's political situation.

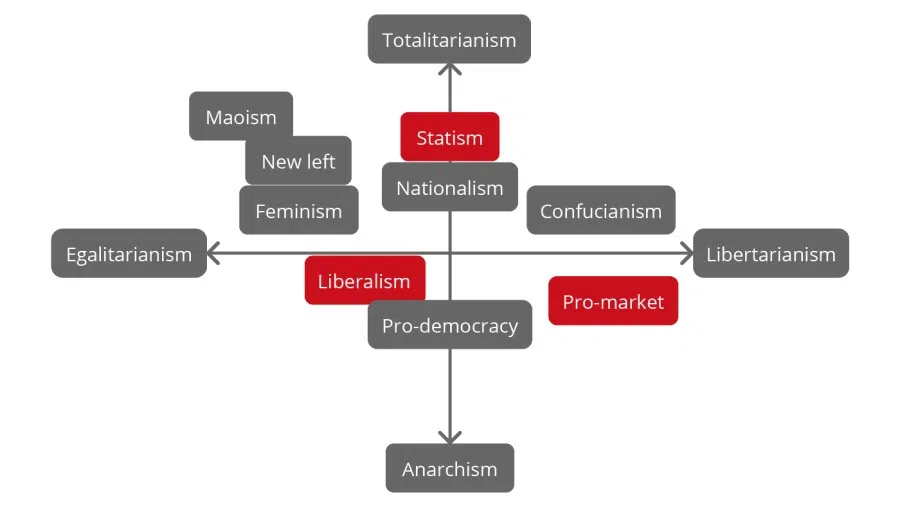

Figure 2 shows the political spectrum in China today. The horizontal axis represents the direction of economic policy orientation, while the vertical axis represents the governance model. Essentially, these depict the ideology and institution of governance.

The two ends of the horizontal axis are egalitarianism and libertarianism, spaced further apart than in Figure 1. As the Chinese government has its own interpretation of "socialism with Chinese characteristics", which has been revised on multiple occasions, "socialism" is not used on the left end of the horizontal axis. The two ends of the vertical axis are totalitarianism and anarchism. The further down one moves along this axis, the less control the government has over society, and the more self-governing the people are.

However, it is useful to further divide liberal-market camp into the liberal camp and pro-market camp, with the former advocating political liberty and the latter valuing economic freedom.

Compared to Zhao Dingxin's left/right model, the spectrum in Figure 2 is a better representation of the schools of political discourses that exist in China today, indicating more accurately where they stand and how they relate to one another. In 2014, French scholar Sebastian Veg proposed a framework similar to Figure 2, with four schools of thought corresponding to the four quadrants. This analysis draws on Veg's work to further categorise and define each school of thought. For example, the New Left is often thought to comprise egalitarianists, statists (国家主义), and nationalists (民族主义). But while the latter two groups do emphasise the authority and responsibilities of the government, they do not necessarily agree with the values of the egalitarianists. For this reason, Figure 2 places them on the upper half of the vertical axis and in the centre of the horizontal axis.

Gao Chaoqun of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences writes that currently there are four schools of political thought in China: soft statism, the liberal-market camp, pro-democracy, and social revolutionism. These have been included in Figure 2. In Gao's view, the nationalists and free market camp are the mainstream while the other two schools are on the margins, a view that aligns quite well with the actual situation in China. However, it is useful to further divide liberal-market camp into the liberal camp and pro-market camp, with the former advocating political liberty and the latter valuing economic freedom. The goal of the pro-democracy camp is for China's political system to adopt the electoral system in the West, which situates this camp in the bottom half of the spectrum. The "social revolutionists" are the left-wing populist Maoists, who are on the extreme end of the leftist camp. While this camp holds some appeal for various groups in the lowest strata of society, it does not attract many supporters from the middle class.

Notably, like the left wing in the West, in recent years China's liberalists have gradually shifted further left. These groups mock and criticise China for lacking both freedom and equality. My own observation is that mainstream liberalism has evolved into left-wing liberalism. US political philosopher John Rawls is admired by such groups, while the pro-market camp idolises libertarianism advocate Friedrich von Hayek. Liberalism and feminism have significant overlap, with the latter being more committed to driving China's identity politics. On the right, the pro-market camp and the Confucianists defend an unequal social system. The former bases its arguments on market competition, while the latter advocates China's traditional moral order.

China's internet community has come up with nicknames for certain groups with political leanings, such as "Party warriors" (五毛党, literally the 50 Cent Party/Army, referring to people reportedly paid 0.50 RMB by the Communist Party for each positive online post related to the Party)...

Since the Chinese people are also divided in where they stand on foreign policy, one might wonder why it is not treated as a dimension of the political spectrum. In 2017, Germany's Mercator Institute for China Studies conducted a detailed analysis of China's online discourse, and it treated universalism/ethnic nationalism as a political dimension. However, I have not included positions on foreign policy as part of Figure 2 for two reasons. First, under normal circumstances, a country's political situation mainly depends on its domestic politics, with its foreign policy emerging as a reaction to domestic politics. Second, a three-dimensional political spectrum is too complex and difficult to render visually.

China's internet community has come up with nicknames for certain groups with political leanings, such as "Party warriors" (五毛党, literally the 50 Cent Party/Army, referring to people reportedly paid 0.50 RMB by the Communist Party for each positive online post related to the Party), the "little nationalists" (小粉红), the "national industrialists" (工业党), and the "US lovers" (美粉). These groups make their voices heard on every public incident in China today, and while these voices exist in both elite classes and common people, the various schools of thought are more likely to be expressed among people of different backgrounds.

Based on the two-dimensional spectrum presented above, it is evident that the various schools of discourses in China are spread through every quadrant, while discourse is becoming more diverse and overlapping, rather than becoming polarised.

A few years ago, two young political scientists working in the US, Jennifer Pan and Xu Yiqing, examined online data related to political views and found that among those living in China, residents in the eastern coastal areas and the highly educated tend to support economic and political freedom, while those who live inland and those who are less educated tend towards the opposite.

Looking again at the article by Zhao Dingxin, one might ask whether China's public discourse is growing increasingly polarised. Relying mainly on anecdotes and personal observations, Prof Zhao does not provide more convincing, solid evidence. Based on the two-dimensional spectrum presented above, it is evident that the various schools of discourses in China are spread through every quadrant, while discourse is becoming more diverse and overlapping, rather than becoming polarised. The report by Mercator Institute reflects a similar conclusion. So, in the foreseeable future, these political narratives will continue to mingle and compete with one another, and together they will determine China's future.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)