China's whole-of-nation push for technological innovation

China's 14th Five-Year Plan was discussed in the fifth Plenum of the 19th Communist Party Congress at the end of October 2020. As expected by many observers, innovation again was underlined in the communique of the 5th plenary session of the 19th CCP Central Committee as well as in the proposals for the 14th Five-Year Plan released in early November 2020. Clearly, there are some important issues to be addressed with innovation.

Innovation is essential for high-quality growth. In other words, innovation will support the growth of productivity in the Chinese economy. Moreover, innovation is essential for developing some core technologies, for example in the semiconductor industry, and in industrial software, etc.

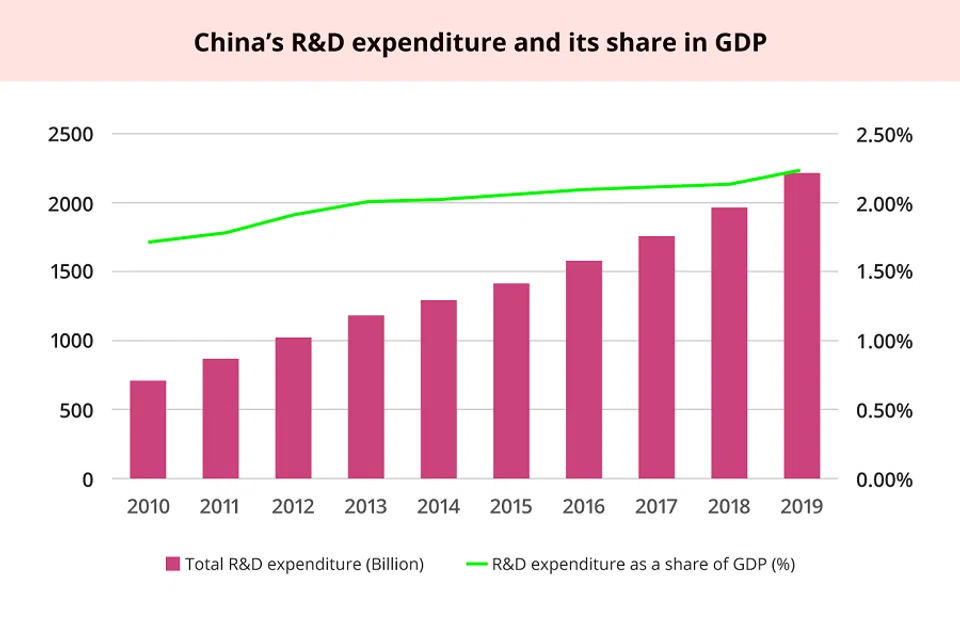

Some points on innovation in the 14th Five-Year Plan are of note. First, China will continue to highlight the importance of financial input for innovation. China's Research and Development (R&D) expenditure is the second highest in the world after the US. R&D expenditure as a share of GDP reached 2.2% in 2019 (Figure 1). However, this is still short of the target (i.e. 2.5% of GDP by 2020) set in the 13th Five-Year Plan, and the ratio continues to lag behind advanced industrialised countries, such as about 2.8% in the US and 3.6% in Japan in 2018.

Focus on basic scientific research and core technologies

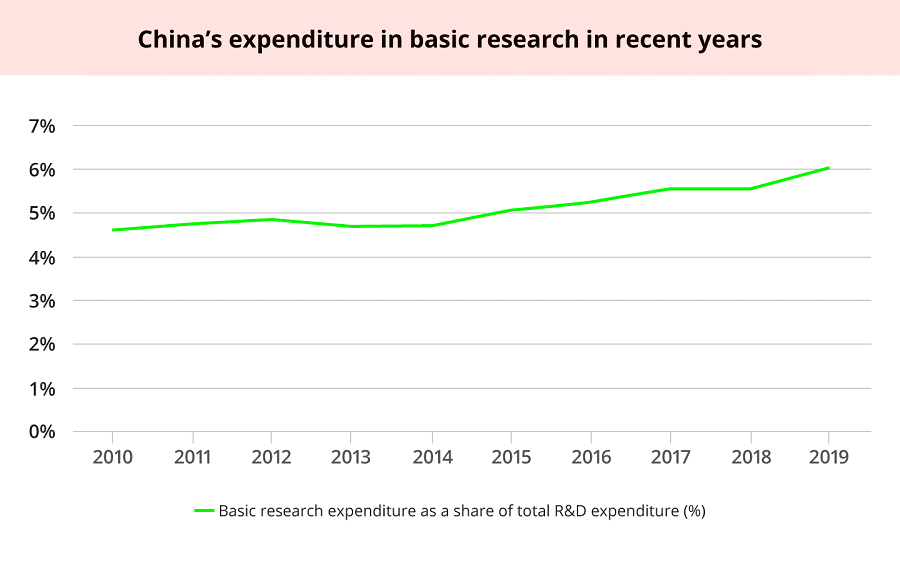

Second, basic scientific research is going to be stressed on in the 14th Five-Year Plan. In 2019, China spent about 6% of R&D expenditure on basic research (Figure 2), which is a figure that is much lower than OECD countries (around 15%). Chinese enterprises only spent 0.3% of their R&D expenditure on basic research in 2019. Policies such as tax rebate, subsidies and financial support are likely to be used to support more basic research conducted by enterprises. For research universities, new types of education and talent programmes in basic research are likely to be further supported by the government.

Third, the development of core technologies will be a priority in the 14th Five-Year Plan. Government inputs in high-technology sectors are likely to increase. For example, government-guided funds (zhengfu yindao jijin, 政府引导基金) could be mobilised as an alternative way to promote investment in high-technology sectors. Furthermore, in 2014 China established the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund (or what is called the "Big Fund") to support the R&D in the semiconductor sector. The first phase of the Big Fund managed to leverage more than 500 billion RMB investment (from both public and private sectors) in the semiconductor industry. It was recently estimated there are over 1,600 government-guided investment funds in total.

Restrictions on access to essential semiconductors and software that are core technologies in the strategic industries that China aims to promote have further amplified the leadership's drive for self-reliance.

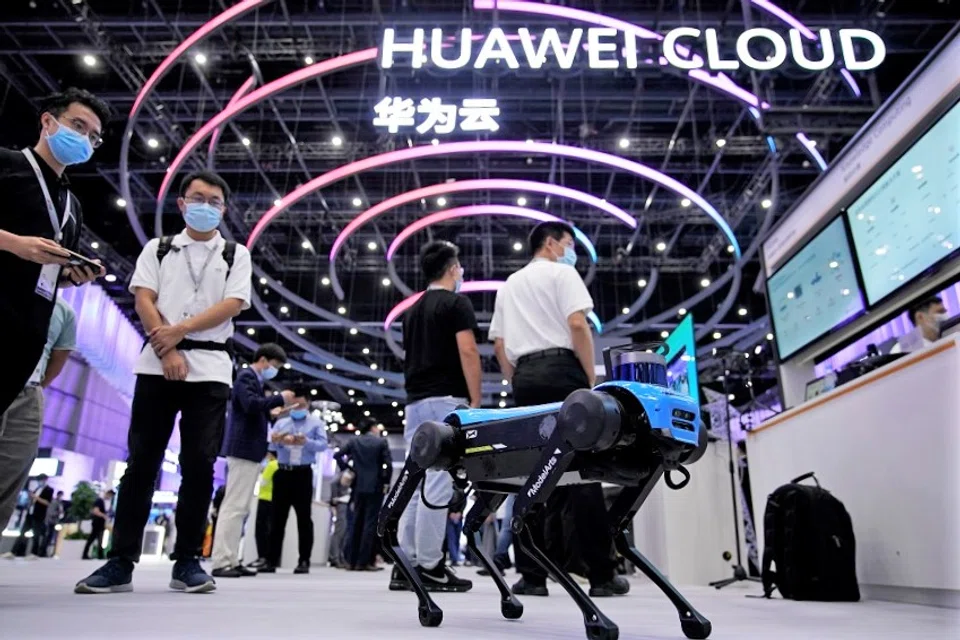

However, the dispute between China and the US over competition in technology and the potential decoupling of innovative systems has become a serious challenge to China's ambition to exploit international linkages and strengthen R&D for core technologies. Most of the actions taken by the US up to 2020 have focused on undermining the efforts of innovative Chinese firms, in particular Huawei, to capture global markets for telecommunications systems such as the 5th generation mobile network (5G) infrastructure.

Actions against Huawei have been taken through a combination of measures. These include erecting export restrictions for semiconductors or advanced design equipment from the US, by placing Huawei and 70 affiliates on the so-called Entity List which restricts business dealings with foreign firms that are considered a national security risk for the US. The US has also attempted to persuade governments overseas to exclude Huawei from participating in the development of their national 5G infrastructure.

Seeking self-reliance in essential semiconductors and software

Restrictions on access to essential semiconductors and software that are core technologies in the strategic industries that China aims to promote have further amplified the leadership's drive for self-reliance. The US ban on sales of American components to ZTE in 2018 exposed a weakness of dependence on foreign technology that shocked China, and the recent trade sanctions on China's largest chipmaker Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC) in 2020, have intensified the leadership's efforts to strengthen the indigenous capacity for development and production of core technologies. The revival of an official reference to self-reliance during Xi Jinping's recent inspection tour to Shenzhen is a clear indication of this strategic goal.

Indeed, the strategic importance of indigenous innovation (perhaps a better term is "Chinese independent innovation") constitutes a major general guideline for policies related to promoting innovation, as illustrated by the following statement in the proposals for the 14th Five-Year Plan: "Being technologically self-sufficient, as well as technologically strong, has been identified as a strategic pillar of national development."

Under the Long-Range Objectives Through the Year 2035, key core technologies are expected to have breakthroughs by 2035.

Given the tensions of the US-China trade war, the conditions for research cooperation and exchange of technology between the two countries have deteriorated. For example, the US government has quoted national security reasons for turning down the visa requests of a number of Chinese scientists wanting to visit the US or attend international conferences in the US. For similar national security reasons, the Chinese government has rejected the visas of some American scholars. Chinese students have also realised that securing a place at US leading universities is becoming increasingly difficult, and have looked elsewhere among English-speaking countries for opportunities to study abroad. A decline in the contributions of Chinese postgraduate candidates may, however, become a future challenge for US universities too.

In the context of US-China technological competition, China is going to allocate a lot of resources to support the country's own innovation capabilities in the next five years. This type of independent innovation is critical for developing some core technologies, for example in the semiconductor industry, in the development of industrial software, etc. Under the Long-Range Objectives Through the Year 2035, key core technologies are expected to have breakthroughs by 2035.

... a follow-up Medium and Long-term Plan for Science and Technology Development for 2020-2035 has been formulated recently, where the strengthening basic science and innovation in more than 50 strategic research directions have been delineated, including seven major sectors covering 30 specific topics.

The government's ambition to promote independent innovation has been underscored for more than a decade, most explicitly since the adoption of the Medium and Long-term Plan for Science and Technology Development (2006-2020) (MLP) in 2006 and the Made in China 2025 Plan in 2015. In spite of international criticism - or perhaps, galvanised by international reactions - the Chinese leadership has continued to adopt new policies that promote efforts by domestic actors to develop new technology. Since the MLP for 2006-2020 will soon end, a follow-up MLP for 2020-2035 has been formulated recently, where the strengthening basic science and innovation in more than 50 strategic research directions have been delineated, including seven major sectors covering 30 specific topics. Many of the priorities will also be included in the implementation sub-plan for S&T under the 14th Five-Year Plan.

Whole-of-nation innovation effort

Another implication of the US-China technological competition is the reinvention of the concept of a whole-of-nation innovative strategy. A "new type" of whole-of-nation institutions has been highlighted in the proposals of the 14th Five-Year Plan. Such whole-of-nation institutions are envisaged to facilitate coordination of R&D activities across different entities including universities, research institutes and enterprises. This type of potential mechanism would also involve a concentration of economic and human resources on a few research units and enterprises.

China remains very proud of the achievements of the concentration of both S&T and economic resources through whole-of-nation mobilisation on the development of atomic and nuclear bombs and satellites in the 1960s. The current leadership is already fond of concentrating national resources on mission-oriented R&D programmes, partly motivated by a problem of fragmentation of initiatives among central ministries and overlapping projects launched by local governments. More resources will therefore be allocated in favour of selective projects, enterprises and research areas in centrally guided key projects, for example in core technologies such as semiconductors and artificial intelligence.

In the years to come, technological innovation is a necessary component in a Chinese strategy to improve the quality and the technological level of supply chains through exploiting the potential economies of scale and scope created by an expanding domestic market and new demand/consumption.

In the 14th Five-Year Plan, this priority is launched in relation to the development of the domestic and international markets according to the principle of "dual circulation". In one sense, this principle reflects a realist interpretation of the current geopolitical environment, with the US threatening to achieve multilateral decoupling of China. But in another sense, it is perhaps a recognition of the need for China to marshal the market demand in a revived post-Covid-19 economy for the innovative forces associated with domestic digitalisation, sustainable development, and high technology industries to achieve a leading position internationally.

Related: China's next Five-Year Plan focuses on security, stability and quality of development; adopts a more subdued tone | China's Five-Year Plan: A bottom-up model of policy making? | China is now 'a moderately affluent society'? | When a nation's Honor is at stake: Huawei's mega sale | Xi's five-year plan for Shenzhen: A hard road ahead? | Clamp down on Chinese students and academics? America's loss is China's gain