Chinese, American and European vaccines - will we have the luxury of choice?

As the Covid-19 outbreak evolves into a global pandemic, developing a vaccine is now the greatest race in history against both the coronavirus and time. Scientists have been working tirelessly on a vaccine since late last year.

China, where the outbreak began, was one of the first countries to start working on a vaccine. Through five different scientific techniques, China has come up with four vaccine candidates for clinical trials.

The fastest progress is made by Major-General Chen Wei's team at the Institute of Military Medicine. Working with Chinese biopharmaceutical company CanSino Biologics, their vaccine candidate became the first to enter the second phase of clinical trials on 12 April. Results are expected this month. (NB: Meanwhile, National Research Council of Canada has announced that it will be working with CanSino to "advance bioprocessing and clinical development in Canada" of the above vaccine candidate known as Ad5-nCoV.)

Recently, the US also started Operation Warp Speed, pulling together pharmaceutical companies, government agencies, and the military, to shorten the vaccine development period by eight months, with a target of producing 100 million vaccine doses by the end of the year. US pharmaceutical company Pfizer and biotech company Moderna have begun clinical testing.

In Europe, a vaccine developed by Oxford University and pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca began clinical trials on 23 April. AstraZeneca expects to produce tens of millions of doses within this year.

Vaccines expected within 12 to 18 months

With over 100 vaccines in development worldwide, does this unprecedented level of research and development mean that a vaccine will be produced quickly?

Developing a vaccine is a long process that usually takes years or even decades. The mumps vaccine took the shortest time - four years.

As a rule, vaccines go through three phases of clinical trials before mass production, to ensure their safety and effectiveness.

The first phase involves administering the potential vaccine to a small group of healthy volunteers to test for safety; phase two tests the effects of the vaccine on test groups including people of various ages and health levels; phase three is the riskiest and most important phase involving the greatest investment - testing the effectiveness of the vaccine on thousands of people before it goes on the market.

...companies are pumping in large amounts of money to set up production facilities even before potential vaccines are proven effective.

A vaccine could save many lives and reduce major economic loss. As the clock ticks amid the pandemic, unconventional routes have been taken to develop a vaccine.

Last month, China started a green channel to allow two vaccines from the Wuhan Institute of Biological Products and Sinovac to combine phase one and two clinical trials.

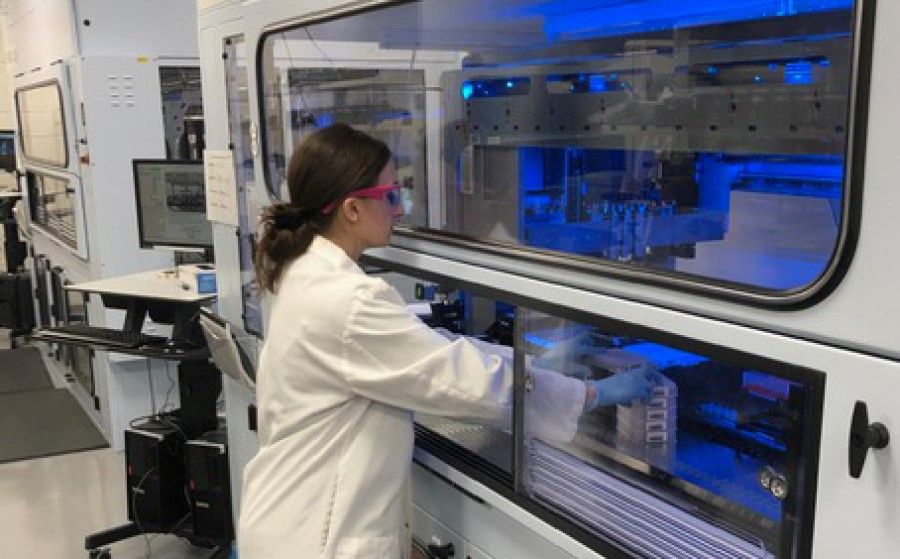

To shorten production time, some pharmaceutical companies are pumping in large amounts of money to set up production facilities even before potential vaccines are proven effective.

The world's largest vaccine producer, the Serum Institute of India, announced that it would begin producing the vaccine from Oxford within this month, even while it is still in clinical trials, in order to immediately put it on the market once it is approved.

Pharmaceutical companies and academic institutions around the world generally expect a vaccine in about 12 to 18 months. If this happens, the new Covid-19 vaccine will be the fastest to be developed. However, many experts are not too optimistic about this timeline.

Experts say vaccines cannot be forced

Dr Ong Siew Hua, director and chief scientist at Acumen Research Laboratories in Singapore, tells Zaobao that the failure rate for vaccine development is over 90%, and is a lot more difficult than imagined.

She says, "Apart from safety and effectiveness, how long will it stay effective, what dosage works, and how long does it take to elicit an immune response - all this takes time to assess, and sometimes it cannot be forced."

New vaccines have to be injected into healthy people, and even if there is a 0.5% chance of severe side effects, the consequences can be worse than a coronavirus infection...

Singapore's Duke-NUS Medical School is working with US company Arcturus Therapeutics to develop a vaccine with a technology that can shorten safety assessment time from a month down to a few days.

Eugenia Ong, a senior researcher with the Emerging Infectious Diseases Programme at Duke-NUS Medical School, says that for a vaccine to reach the second or third phase clinical trial, it will take at least 12 to 18 months, and whether it is finally approved for public use depends on the results of the later clinical trials.

She adds: "Technological developments allow faster development and production of vaccines, but safety cannot be compromised."

New vaccines have to be injected into healthy people, and even if there is a 0.5% chance of severe side effects, the consequences can be worse than a coronavirus infection, and so scientists have to be especially careful.

Experts also warn about antibody-dependent enhancement. In this phenomenon, not only will the body not produce an effective immune response to the vaccine, but the vaccine also strengthens the reproductive capabilities and infectiousness of the virus, resulting in more severe symptoms. This is one of the main obstacles to developing a vaccine for dengue fever in the past decades.

Strict conditions for mass production and transportation of vaccines

Even if a vaccine is proven safe and effective in the lab, that does not mean the work is done. Challenges in mass production and transportation of vaccines cannot be overlooked.

Clinical development costs for each vaccine would be at least US$500 million.

Dr Ong Siew Hua says, "For various reasons, it may not be possible to mass-produce vaccines developed in the lab, or production costs might be too high."

According to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (GAVI), a company with existing production facilities and trained staff would have to spend about US$50 million (S$70 million) to produce a few hundred million doses of a single vaccine. On the other hand, a company starting from scratch might have to spend about US$70 million, or even more if the vaccine requires building new technology platforms. Clinical development costs for each vaccine would be at least US$500 million.

In terms of storage and transportation, common vaccines are stored at 4 degrees Celsius, which is the temperature of most refrigerators, which makes storage and transportation comparatively easy. But not all vaccines are the same.

Bill Gates, co-founder of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, wrote a post saying that RNA vaccines need to be stored at much colder temperatures, as low as -80 degrees Celsius, which would be a challenge for transportation.

RNA vaccines work on the principle of giving the body the genetic code needed to produce antigens against viruses, which is one of the types of vaccines currently being researched.

Possible that vaccine may not be found

Scientists are also not ruling out the possibility that a vaccine may not be found. The truth is there are no vaccines for many infectious diseases such as AIDS and Zika. Governments' short-sightedness and the nature of capitalism usually lead to a sharp drop in the desire to develop a vaccine, once the outbreak eases.

When SARS broke out in 2003, some governments and research organisations put in a lot of resources to develop a vaccine, but when the outbreak was brought under control, the research died down.

Dr Ong Siew Hua hopes that this time, efforts to find a vaccine will not cease.

"If another coronavirus appears, such research will be valuable. Covid-19 is also a coronavirus like SARS in 2003. If the research on SARS had succeeded, who knows? it could have helped."

Distribution of vaccines will determine if the Covid-19 pandemic can be curbed

It is inevitable that countries would prioritise their own citizens in the face of a public health crisis. Rich countries would either purchase a large amount of vaccines for their country, or prevent the export of vaccines to other countries.

Additionally, vaccine manufacturers in pursuit of commercial profits would also adopt the "highest bid wins" method, selling the vaccines to the buyer with the highest offer.

"If there is no prior agreement on a plan to share vaccines, the distribution of vaccines would become an ugly geopolitical battle, resulting in the loss of more lives." - Susan Shirk, Chair of the 21st Century China Centre, University of California, San Diego

However, the ones most in need of the vaccines are the citizens of lower-income countries with limited purchasing power. As their public healthcare systems are underdeveloped, these countries are unable to effectively trace, quarantine, and treat infected patients, increasing the risk of an uncontrollable outbreak as a result.

Susan Shirk, former US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State and chair of the 21st Century China Centre at the University of California, San Diego, tells us in an interview: "If there is no prior agreement on a plan to share vaccines, the distribution of vaccines would become an ugly geopolitical battle, resulting in the loss of more lives."

2009 H1N1 pandemic repeating itself?

Seth Berkley, CEO of GAVI, published an opinion piece on The New York Times recently in which he said that the likelihood of the vaccine being able to stop the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic depends on whether all countries have access to it. Judging by what happened during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the prospect of arresting the pandemic is not very good.

He said due to export restrictions of countries producing the vaccines, and manufacturing agreements, the vaccine developed for the 2009 H1N1 virus was mainly sold to rich countries, leaving the rest of the world without access. If the same scenario were to happen, this pandemic that has already caused over 200,000 deaths worldwide would continue to spread and take more lives.

Countries need to come up with collaborative framework

As no one knows which team of scientists would develop a vaccine first, Shirk believes that now is the time to reach an agreement on a fair vaccine-sharing plan.

She says, "Each country would definitely want to keep the vaccine to themselves, but if we want to resume commercial activities and travel, we would also hope that the hot spots of other countries, especially poorer countries, would have access to the vaccine as well."

"Whether the US, China, or Europe develops a vaccine first, it will be difficult to ask the WHO to distribute them." - Professor Wu Xinbo, dean of Fudan University's Institute of International Studies

Aware of the likely calculations at play, Shirk is calling for countries to come up with a collaborative framework that teases out various issues of vaccine development, testing, production, and fair distribution. She believes that the G20 or the World Health Organisation (WHO) would be good platforms to advocate such collaborative frameworks.

However, with the politicisation of the Covid-19 pandemic, such collaboration will be tough.

Professor Wu Xinbo, dean of Fudan University's Institute of International Studies, says, "Currently, each country is developing a vaccine themselves. Whether the US, China, or Europe develops a vaccine first, it will be difficult to ask the WHO to distribute them. The WHO could coordinate the collaboration of scientists globally, but even this is a difficult task as well."

Academics say the coronavirus vaccine is a strategic resource

As the intense vaccine battle rages on among countries, academics interviewed point out that the vaccine has already become a strategic resource under the present coronavirus crisis. The significance of emerging as victors in this battle exceeds health and medicine - it extends to the realms of security, politics, and international strategy.

Prof Wu is one of the scholars who describes the vaccine as a "strategic resource" amid the coronavirus pandemic. "Under current circumstances, whoever has the vaccine now would be like whoever had nuclear weapons during the Cold War," he says.

"This would also bring China an enormous commercial market, and become an important diplomatic bargaining chip." - Professor Wu Xinbo

He points out that countries are faced with three variables amid the present crisis: whether they can effectively contain the outbreak; whether they can quickly restore their economy; and whether they can quickly release a vaccine.

He says, "China is doing well on the first two points. What's crucial now is if it can quickly develop a vaccine... Once a vaccine is developed, there is no need to worry about a resurgence of the outbreak, and the economy, society, and even politics will be stabilised. China will also gain an enormous commercial market, and have an important diplomatic bargaining chip."

Prof Wu believes that if China is able to take the lead in developing a vaccine and provide the vaccine to the international community, its international image will improve.

Like 5G technology and chips, bio-medicine is another strategic industry that China's "Made in China 2025" plan prioritises. Providing the world with a coronavirus vaccine will also elevate China's position as a global power of science and healthcare.

China should strengthen cooperation with Europe in vaccine research and development

Professor Chen Bo of Huazhong University of Science and Technology tells us in an interview, "Under such intense China-US competition, if China is able to develop a reliable vaccine first, it would be a strong signal to other countries that China's research and manufacturing capabilities have already reached a high level and are almost on par with the US."

As China's vaccine industry has been plagued by quality problems, even its own citizens may not have adequate confidence in domestically produced vaccines.

Apart from a large volume of research work to do, China also needs to rebuild the confidence of external parties in its vaccines.

As China's vaccine industry has been plagued by quality problems, even its own citizens may not have adequate confidence in domestically produced vaccines. The Wuhan Institute of Biological Products - now involved in coronavirus vaccine development and starting on clinical trials - was involved in controversy two years ago for producing over 400,000 doses of ineffective vaccines for whooping cough, diphtheria and tetanus.

...as external parties would not have confidence in China's vaccine and China would continue to be stigmatised by the US, any vaccine that China develops first would be called into question.

Additionally, with China and some Western countries currently sparring over the origins of the coronavirus, strong political factors would come into play with regards to whether the international community would recognise the coronavirus vaccine developed by China.

Prof Chen thinks that as external parties would not have confidence in China's vaccine and China would continue to be stigmatised by the US, any vaccine that China develops first would be called into question. He thus believes that China should strengthen its cooperation with Europe in vaccine research and development.

"This will then show the world that China wishes to cooperate to bring about a win-win situation. With the participation and 'endorsement' of developed countries, less doubt would be cast on the vaccine, helping external parties to trust that China's vaccines are reliable," he explains.