A Chinese woman's status and the one-child policy

Lorna Wei notes that gender-skewed policies such as the one-child policy have far-reaching consequences and often produce unexpected outcomes. Social issues will persist if we continue to ignore the warning signs given by those who bear the brunt of such policies.

China's notorious one-child policy that was in place from September 1980 to January 2016 is regarded as a severe violation of human rights. Admit it or not, there are a series of scary and destructive side effects due to this so-called inhuman policy: infanticide, sex-selective abortion, son preference, and sexism. Out of all the negative consequences, female infanticide is the most horrible one, as the Amazon documentary One Child Nation indicates.

Chinese people are also aware of the policy's terrible effects. In 2015, an adapted version of the popular song Love for Sale (爱情买卖) was circulated widely on Sina Weibo (新浪微博) and bilibili (哔哩哔哩), two influential "we-media" channels in mainland China that give individuals a platform to upload and share content directly with their followers. This sarcastic and brutally honest song criticised those who wanted to have a son in the era of the one-child policy and then chose the abortion of baby girls. It goes like this:

当初是你要堕胎,堕胎就堕胎。

It was you who insisted on having abortions.

现在又要女人爱, 女人哪里来。

It is you who wants women now. Where are the women?

你家儿媳土里埋,已有二十载。贞子花子伽椰子,今晚招婿来。

They've been buried in the earth for 20 years. There are no women, but female ghosts.

当初是谁要男孩,一再堕女胎?如今这帮繁殖癌,想起媳妇来

Who insisted on having boys and aborting girls? Now you want a daughter-in-law for your son.

你家儿媳土里埋,水里重投胎。砸锅卖铁娶不来,活你TM该。

Your daughter-in-law was buried or drowned. You deserve this, no matter how much money you offer.

The sin of being female

As shown in the lyrics, it was hard for baby girls to survive in the era of the one-child policy. The policy is a subcategory of the fertility policy in China, which refers to the norms formulated by the Chinese government (or under the guidance of the state). It regulates the reproductive behaviour of couples, including the quantity (one or two) and quality (intelligence and physical health) of births. China currently adopts the two-children policy (全面二孩政策), which means that one couple can have two children at most.

Though fertility policy is applied nationwide, the one-child policy was implemented differently in urban and rural areas. Most urban citizens enforced this fundamental national policy strictly, while in the rural areas, it was the government that compromised: if the first child was a girl, the rural parents could have a second child. In this sense, the first baby girl was regarded as half child and the one-child policy turned into one-and-half-child policy (one elder daughter + one younger son) in rural areas.

Nothing could stop the son preference in China, despite the governmental restrictions on fertility. For instance, some urban citizens changed their household registration (or hukou 户口) to avoid penalty on having an extra child. The rural citizens gave birth to as many children as possible, until they had a son. Some rural citizens abandoned their daughters, refused to register their daughters' hukou status, and even killed the baby girls in the cradle.

Every action has an equal and opposite reaction

The twisted era has great influences on Chinese society which are beyond what the state or citizens could imagine. One of the significant outcomes is Chinese women's increasing status. For example, urban women are empowered with unprecedented economic power. For urban citizens, those who violate the one-child policy face huge amounts of penalty and even lose their jobs. As a result, urban parents try their best to raise their only daughter, offering girls with more education opportunities and economic resources.

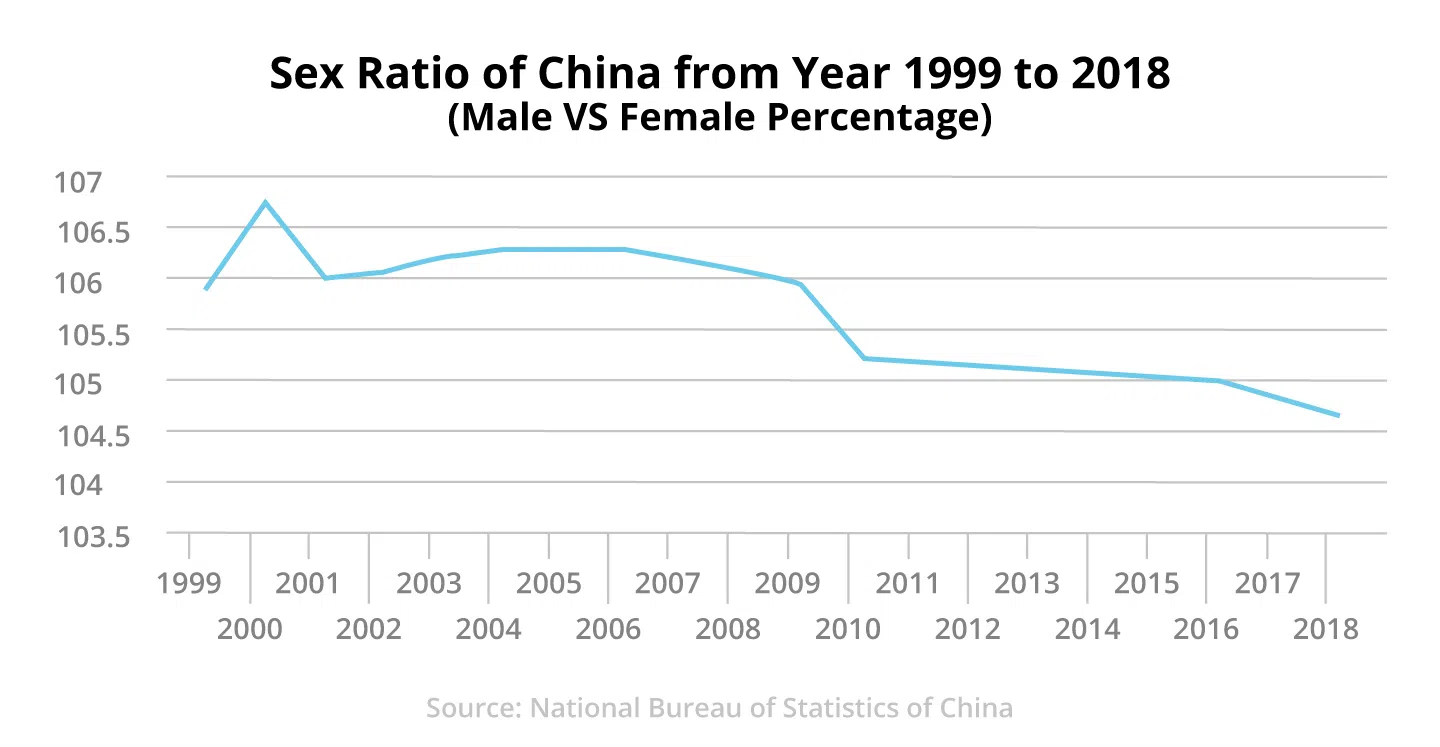

In rural areas, women have an advantage in the current marriage-squeezed rural areas. Although men are more valued at birth, leading to the practice of female infanticide, the relatively limited number of women who reach marriageable age become a desirable asset to continue the familial line. The imbalanced sex ratio (Figure 1) allows scarce brides to ask for sky-high bride prices. Ironically, the sexist one-child policy exacerbates the equally sexist practice of bride price - only the other way round.

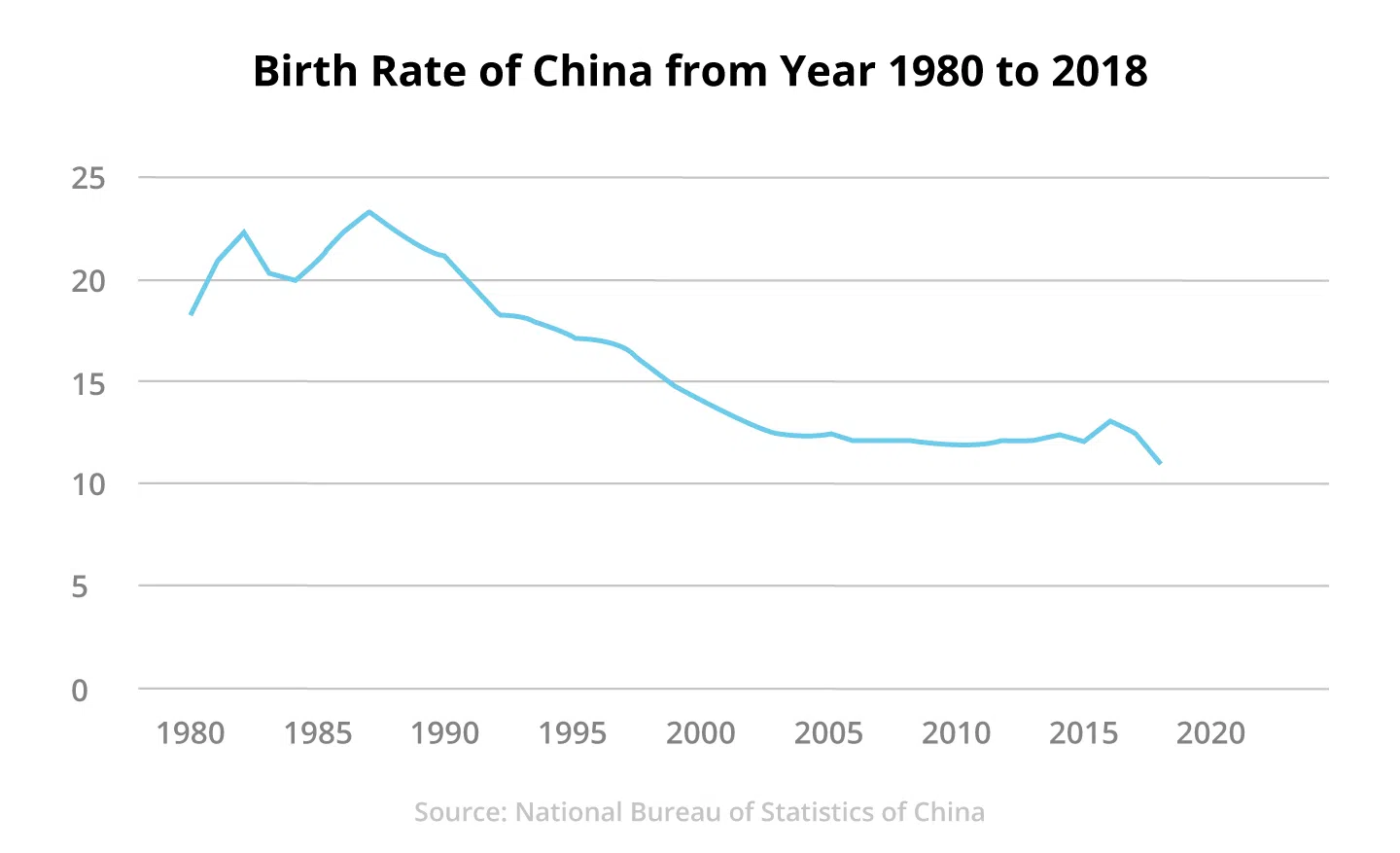

Another unexpected consequence is the decreasing birth rate. In the era of one-child policy, the Chinese government told the citizens to have one child for the sustainable development of the country, while in the era of the two-children policy (from 2016 to the present), the government tells the citizens to have two children, again, for the sake of the better development of the country.

In terms of fertility, it is the state that tells citizens what to do, but its propaganda seems to be ineffective now. The subtle changes in state-citizen relations such that the people no longer take the government's words at face value also influence the mindset of Chinese people: the obsession on raising children for aging (养儿防老) becomes cost-ineffective because of increasing housing prices, living standards, and child-raising costs. Though the government persuades young people to be more responsible for the family and country, staying unmarried and childless still gains popularity. The new generation is more realistic. They ask, "if we cannot have a decent life, how can we be responsible for another human?"

The fertility policy in China reflects the government's trials and errors in the construction of "socialism with Chinese characteristics" (中国特色社会主义), a concept described by Deng Xiaoping as adapting socialism to Chinese conditions.

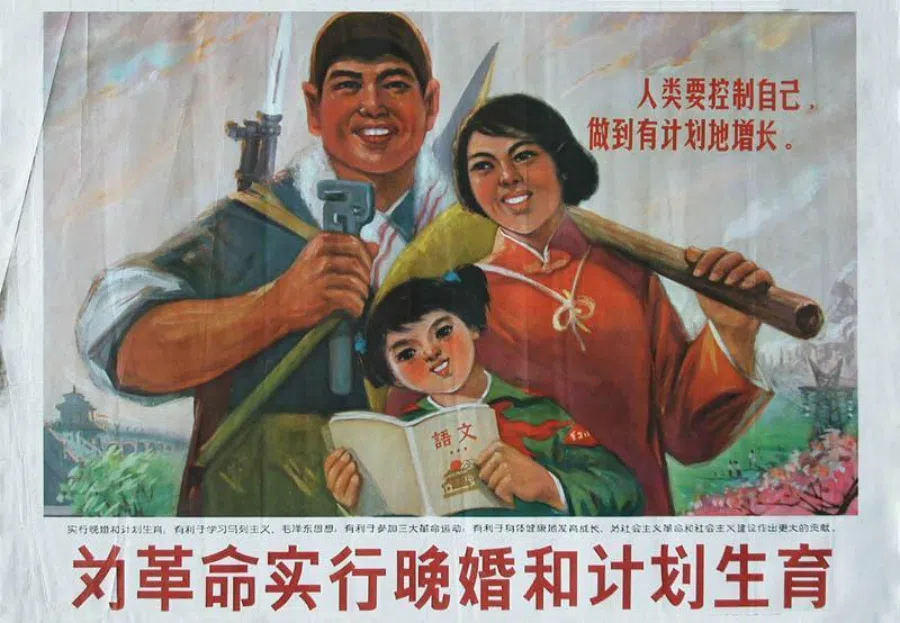

Chinese people have lived through ever-changing fertility policies in the last few decades: from the slogan of "More people, more power" (人多力量大) in Mao's era (1949-1878) and "It is better to shed blood in the river than to have one extra baby" (宁可血流成河,不可超生一个) in the era of one-child policy, to the current propaganda of two-child policy "One couple with two children are not afraid of aging anymore" (一对夫妻生俩娃,老有所养不再怕). Most Chinese people truly understand the state's dilemma and ambition in ensuring sustainable development for the country, but it is the ordinary people who suffer the cost of the one-child policy.

In the hierarchical Chinese society, the country's interest, that is, the interests of the ruling class, is the priority. Among the ordinary people, women are of secondary consideration in the male-dominant China. Paradoxically, though some women lose their chance at life by the immature and compulsory one-child policy, those who survive gain more power. If the status quo remains, more unexpected consequences of governmental policies would spring up in the next decades. If the foundation shakes, would the top be safe anymore?