Deepening China-Iran relations could change global geopolitics

The New York Times reported, based largely on an 18-page proposed agreement it had obtained, that China and Iran are on the verge of signing a 25-year investment-for-oil deal of the century worth US$400 billion. While the authenticity of this agreement remains in question, deepening cooperation between China and Iran in recent years is an indisputable fact.

Following the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal concluded between Iran and the P5+1 countries (China, France, Germany, the UK, Russia and the US), China and Iran released a "Joint Statement on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership" during President Xi Jinping's visit to Iran in 2016. The partnership aims to deepen cooperation between both countries in various aspects and align China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with Iran's development plan. Working towards concluding a "bilateral 25-year Comprehensive Cooperation Agreement" is also hinted at. Under such circumstances, the New York Times report of a China-Iran deal of the century seems possible, as it fulfils their comprehensive strategic partnership in some ways.

Misery loves company?

This so-called China-Iran deal of the century has come under intense scrutiny because relations among China, the US, and Iran have undergone tremendous changes since 2018. In upping the ante against Iran in favour of Israel, the Donald J. Trump administration has been unilaterally destroying the JCPOA, imposing harsher sanctions on Iran, and even illegally assassinating Iranian major general Qasem Soleimani, in a show of its policy of "maximum pressure" toward Iran.

The partnership could affect the future trend of China-US relations, as well as continental (Eurasia) and oceanic (Indian and Pacific Oceans) relations that are far more important, long term, complex, and extensive.

China-US relations are also going down a similar path to some extent, having rapidly deteriorated since the onset of the tariff war in August 2018. US Vice President Mike Pence's speech later that year in October also foreshadowed a paradigm shift in the US's China policy. At the end of 2018, Pence even threatened a Cold War against China. Most recently, factors such as the Covid-19 pandemic that had emerged from China and the rising coronavirus death toll in the US, coupled with the Xinjiang and Hong Kong issues and the upcoming US presidential elections, have led to military tensions between China and the US in the South China Sea.

Shifting sands of ties in the Middle East, South Asia and Central Asia

Against the backdrop of the aforementioned developments, the New York Times' report of a China-Iran deal has accentuated geopolitical changes in the Middle East, South Asia, and Central Asia. The partnership could affect the future trend of China-US relations, as well as continental (Eurasia) and oceanic (Indian and Pacific Oceans) relations that are far more important, long term, complex, and extensive.

The US and its allies' recent acts of flexing its military muscles in the South China Sea, Bay of Bengal, and Arabian Sea have exposed the vulnerabilities of sea routes amid China-US confrontations at sea. Being in close proximity to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC, a key part of the BRI in Pakistan), long-term investments in Iranian oil and gas can thus add another layer of protection to China's energy security. This also explains why over half of China's investments in the said China-Iran agreement would go to the energy industry.

... these relatively stable land-sea structural antagonisms are helpful in forging long-term comprehensive cooperation between China and major Eurasian countries - especially middle powers Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey - in the foreseeable future.

Under current circumstances, China and Iran's potential large-scale exclusive cooperation not only attests to the sea power theory espoused by Alfred Thayer Mahan (American strategist and author of The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1669-1783), it also deals with its theoretical possibilities. That is, China is strengthening its navy in a bid to catch up with the military forces of the US and its allies on one hand, while strengthening cooperation with the Eurasian continent; establishing strategic partnerships with major Eurasian countries including Russia, Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey; and opening up and connecting land routes through transportation projects such as the Eurasian Land Bridge and the CPEC in correspondence to sea routes dominated by the US and its allies on the other.

Some sort of structural antagonism exists between the above-mentioned Eurasian countries and the US and its allies vis-à-vis Pakistan and India, Iran and Israel, China and the US, and Russia and the US. From a geopolitical perspective, these relatively stable land-sea structural antagonisms are helpful in forging long-term comprehensive cooperation between China and major Eurasian countries - especially middle powers Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey - in the foreseeable future.

It is also imperative for Iran to choose to cooperate with Asian countries, especially Eurasian countries.

Gaining footholds in Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific

From Iran's perspective, developing a comprehensive relationship with China would become an inevitable strategic trend in the future. Under long-term siege by Arab monarchies and facing a possible Arab-Israel-US alliance on its western flank, Iran's "westward movements" (for example, in Syria) have proven too hefty a price to pay. It is also imperative for Iran to choose to cooperate with Asian countries, especially Eurasian countries. At the Kuala Lumpur Summit last year, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani proposed forging ties with major Asian countries by looking East, while former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad highlighted China's positive role in the economic and technological development of middle-sized Muslim powers. In early 2020, Iranian Ambassador to Pakistan Syed Mohammad Ali Hosseini publicly suggested that Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, Russia, and China could form a new alliance.

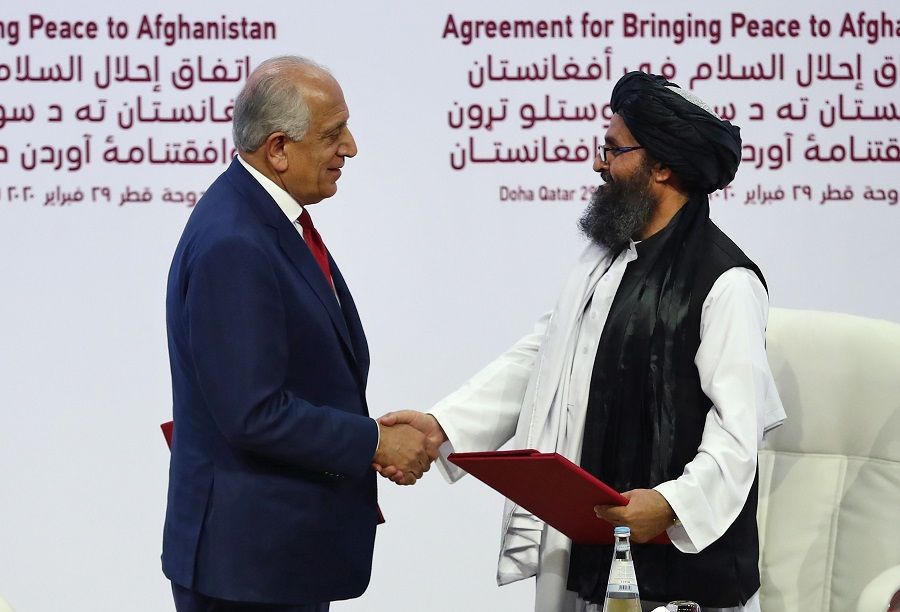

Deepening cooperation between major Eurasian countries including China and Iran is also a necessary development that is in line with the political changes in Afghanistan, which lies at the heart of Eurasia. The peace deal between the US and Taliban inked in Doha called for a full withdrawal of American combat troops from Afghanistan. Due to geographical, historical, linguistic, cultural, and religious factors, the aforementioned Eurasian countries are the real stakeholders in Afghanistan's peace talks and reconstruction for the long run. Importantly, these countries are also connected to two major forces of Afghanistan: the Kabul regime and the Taliban forces. These factors imply that land connectivity between Iran and China - be it connected via Pakistan via land or sea, the future Afghanistan, or Central Asia - is not out of reach.

Almost happening at the same time as when the China-Iran deal of the century came to light, Iran reportedly dropped India from the Chabahar port railway project that would connect its borderlands to Afghanistan.

Amid America's withdrawal from Afghanistan and its containment of China, it is highly likely that India will follow American strategies to downgrade its Central-South Asia integration ambitions and to deepen its cooperation with the US in the Indo-Pacific. The US-Taliban peace deal and worsening US-Iran relations have dealt a great blow to India's efforts at advancing the integration of Central and South Asia. India has attempted to connect to Afghanistan via the Chabahar Port, bypassing Pakistan. Almost happening at the same time as when the China-Iran deal of the century came to light, Iran reportedly dropped India from the Chabahar port railway project that would connect its borderlands to Afghanistan. (NB: The Iranian government said Iran has never inked any deal with India regarding the Chabahar-Zahedan railway, according to an Aljazeera report.)

... deepening China-Iran relations are not only driven by external super-power pressure, but also a natural response to military and political dynamics in Inner Asia following the US retreat from Afghanistan.

This development symbolises India's exit from a key infrastructure project, and also implies that India has - be it out of objective or subjective reasons - redressed its reliance on the US's impractical Central and South Asia policy (such as the so-called New Silk Road Initiative), and begun to build its sea power and form a naval alliance after decade-long attempts in Central Asia following the US war in Afghanistan.

India's reduction of influence from Central and South Asia - especially Afghanistan and Iran - would prompt Iran to find an alternative non-Western major power to take its place. At the same time, as the US and its allies are suppressing Chinese enterprises, China has to deepen and expand neighbouring markets that are safer. From a large perspective, the global US-China competition would force China to take its BRI down a peg from global heights to a regional level. In this way, deepening China-Iran relations are not only driven by external super-power pressure, but also a natural response to military and political dynamics in Inner Asia following the US retreat from Afghanistan.

Although China's strategic partnerships with Russia, Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey do not have the aim or might to form a continental alliance of Eurasian countries (like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation) with the capacity to contend with an Indo-Pacific sea power alliance, they are unique in the sense that the players are not only Eurasian countries but also Indo-Pacific rim countries. Should these strategic partnerships produce groundbreaking railway and highway projects that can link up countries that are both on the Indo-Pacific rim and Eurasian continental edge - such as China, Pakistan, Russia, Iran, and even Turkey - global geopolitics would be fundamentally changed.

Related: Battling atheist China: US highlights Xinjiang issue and religious freedom in Indo-Pacific region | Xinjiang - the new Palestinian issue? | Israel: Caught between a rock and a hard place with China and the US | In a world split apart, where do you belong? | There will be no peaceful rise - China-US relations enters a new phase