Hong Kong: The perils of state corporatism

Influential Hong Kong political commentator Simon Shen argues that Beijing is seeking to control the economic and political freedoms of the Hong Kong people by controlling the business community. He cautions against state corporatism of the sort employed in fascist states of the past and discusses how such state control can creep into our everyday lives.

There is, it is said, no going back for Hong Kong. It is hurtling towards the "one country" end of the "one country, two systems" spectrum. Beyond the issues we have talked about - police and governmental brutality, freedom of speech, freedom of association, the White Terror - there is also an unusual development in our business community.

Various transnational corporations with ties to Hong Kong saw staff changes a month ago: management personnel left HSBC and Cathay Pacific; Sun Hung Kai Properties appointed, for the first time, a mainland Chinese entrepreneur as an independent non-executive director; and Cathay Pacific and Cathay Dragon retrenched many aircrew personnel. Among these aircrews was a good friend of mine who did nothing more than upload a yellow ribbon on Facebook. Cases like this are too numerous to count and have become a terrifying new normal in Hong Kong.

As I write this on a Cathay Pacific airplane 30,000 feet in the air, flight attendants come to me quietly to thank me for speaking out, lamenting that they "don't dare to say anything now". They can only express their gratitude by giving me a cup of noodles. Dialogues like this are incredibly sad. Since when have our airlines - the airlines of us Hong Kongers - fallen so low?

Shades of corporatism

Writing for the South China Morning Post some time ago, senior editor Tom Holland pointed out that Hong Kong faced a "future of corporatism". Getting or losing a job will no longer be about capability. What takes priority will be one's political stance. The state machinery will intervene in the affairs of private corporations through different means, seeking to control the economic and political freedoms of the people by controlling the business community.

Corporatism is nothing new, of course. Back in the late 19th century, when there was a need to counteract the radical reforms that communism stood for and address the difficulties of the working class under capitalism, some intellectuals in Europe chose to envision a middle path. Their idea was that various corporations should be engaged, and the issues of the distribution of social resources and power were to be resolved through negotiation and consensus.

Corporatism differs from capitalism which prizes competition among individuals, and communism which emphasises the struggle of the collective. It lets an elite be nominated by different corporations as representatives of the pertinent social classes, ideologies and interests. Members of this elite are to convene and discuss political and related matters, and come to a common understanding. The state machinery would then implement the consensus reached, thereby feeding the benefits back to the society at large.

In theory, such a mechanism can unite the elite and general populace. With respected members of society leading with wisdom and benevolence, policies that reflect the views of different sectors and the masses would be put forth. Ultimately, policies that serve the public interest best would be arrived at through rational discussion. This not only protects the interests of the bourgeoisie, but also takes into account the sentiments of the working class.

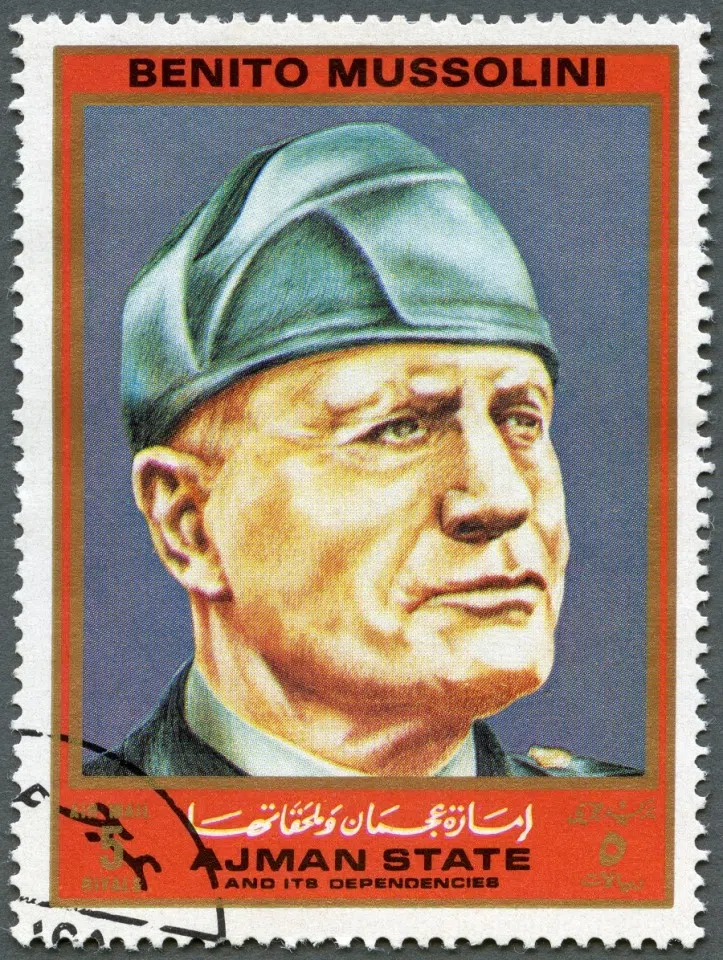

Yet, if we look at the many polities recognised by academia as corporatist - Italy under Mussolini, Hitler's Nazi Germany, Spain under Franco, Brazil under Getúlio Vargas and Argentina under Perón - they are all associated with fascist and totalitarian governments. Although Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal has also been described as "corporatist" by James Q. Whitman, a law professor at Yale University, the international community does not associate it with fascism. So what's the difference?

According to the politics scholar Philippe Schmitter, under rule by "corporatism" in a fascist polity, the "corporate proxies" nominated by the "corporations" organised by the regime are almost always proxies and stakeholders of the regime. Mussolini's legislature with its Chamber of Fasci and Corporations is a textbook example of such a model. Schmitter calls this "state corporatism".

On the other hand, there is a variant of corporatism known as societal corporatism or neo corporatism. When political parties of democratic countries in continental Europe go through proportional representation elections and form coalition governments, the parties mostly come from a background of trade unions and chambers of commerce, making it necessary in these countries to show goodwill to both businesses and the working class. Failure to do so would mean facing punishment in the next election. Such societal corporatism - first bottom-up and then reaching back down - was one of the major reasons why post-war Western Europe did not lean towards the Soviet Union.

State corporatism rearing its head in Hong Kong?

In the case of Hong Kong, functional constituencies (non-geographical constituencies made up of professional and special interest groups) had been introduced into its legislature during British rule. Representatives of various sectors elected through localised elections were included to bring major stakeholders of the colonial economy into the Legislative Council. This answered growing calls for democratisation, and helped guard against the election of undesirable representatives through total democratisation. The idea was to prevent radical pro-China individuals from gaining great influence.

In recent years, however, the SAR government are more and more inclined towards raising sectoral leaders purely on the basis of their loyalty, rather than accepting the true elite chosen by the sectors themselves.

Beijing accepted the mechanism at first, because the functional constituencies kept the business elite within the establishment, and helped calm unease during the transition period. The differentiation of "corporate sectors" by industries was not a bad thing for the Communist Party, which was, after all, adept at establishing trade unions and a united front. Many of the trade unions and guilds that had gone underground after the 1967 Hong Kong riots were thus able to reorganise themselves and bided their time until they could join the establishment.

Under "One Country, Two Systems" 1.0 after Hong Kong's handover, there were still enlightened representatives of the industrial and commercial sectors like James Tien and Selina Chow who took functional constituency seats in the Legislative Council. There was still a semblance of societal corporatism.

In recent years, however, the SAR government (and the Liaison Office of the Central People's Government behind it) are more and more inclined towards raising sectoral leaders purely on the basis of their loyalty, rather than accepting the true elite chosen by the sectors themselves.

Appointing such people to positions in advisory and decision-making bodies fails on two accounts. Firstly, there is no true sectoral representation. Secondly, the balance of interests between the different sectors is upset by "personal interests". This greatly reinforces the common folk's perception of officials and businessmen being in cahoots with each other. Their interests come across as more closely connected than ever, and the government loses its sectoral neutrality.

The government has to constantly give in to sectoral interests to ensure smooth governance, to prevent situations like the business community's about-turn with regard to Article 23 of the Basic Law. The business community, on the other hand, is worried that it could be betting on the wrong horse, and would rather wait for clear instructions before it expresses opinions publicly. Unfortunately, such a politico-business symbiosis can never satisfy the true stakeholders in society. It is ineffective even in maintaining stability. Hence, the authorities can only resort to the exertion of high pressure with brutish violence.

Changeover for a "second handover"

This shift has a great impact on Hong Kong. The societal corporatism under British rule and in the early years of the SAR was a long way from fascism. The elections then had a certain degree of competition, no matter how insignificant - they were "imperfect but acceptable". In addition, with Hong Kong being one of the world's freest economies, even though political life was gradually becoming suffocating, life in the economic domain and political freedom in the private domain were still - in theory - guaranteed by the Basic Law up until June 2019.

These corporate organisations were ostensibly set up for helping the country's development, but in reality, they were there to actualise the "right of total governance" over everything from political to economic life.

Unfortunately, the state corporatism under a totalitarian state as promoted by the SAR government today is predicated on control over both the public and the private domains. Its basis of governance is control over the political and economic life of the people, so as to achieve what the historian Stanley G. Payne underscores as the fascist goal of establishing a despotic economic and social system.

We need only look at the wisdom exhibited by its global antecedents: how fascist Italy's Confindustria (representative of the trade associations) and the fascist trade unions agreed to recognise each other as the "legal representatives", and thus excluded non-fascist trade unions from the whole system; how the Portuguese junta controlled the lifeblood of national development via state-owned enterprises and state-private joint ventures; how many totalitarian states set up their own secret police through corporations to monitor the whole order round the clock. These corporate organisations were ostensibly set up for helping the country's development, but in reality, they were there to actualise the "right of total governance" over everything from political to economic life.

The current enhanced efforts to set the house in order is really about putting an end to societal corporatism, and introducing state corporatism led by the "one country" mantra.

Since Leung Chun-ying took office in 2012, there had been attempts to restrict our freedoms, but, generally speaking, there was still ample resistance in society. The traditional elites of the business, professional and legal communities still had tight control over the financial machine that was Hong Kong. However, even after the rise of the Chinese economy, the percentage of foreign direct investments received through Hong Kong did not decrease, but rose instead.

The increased reliance on Hong Kong is one of the reasons for Beijing's continued need for "a second handover". In order to expand the "right of total governance", it becomes a matter of course to replace old blood with the new in the various sectors, and cultivate corporate bodies that are loyal to the state. 2019's anti-extradition bill movement had strong support behind the scenes from the business community, which Beijing was particularly displeased about. The current enhanced efforts to set the house in order is really about putting an end to societal corporatism, and introducing state corporatism led by the "one country" mantra. The chaotic situation has become an opportunity for a great purge.

The yellow economic circle response to state corporatism

There are endless ways of changing the guard. It can be done through "corporate credit ratings", where companies from unrelated lineage will find it difficult to secure contracts. Direct restrictions on market entry can also be applied to compel cooperation. "Conditions for cooperation" are a corporate decision and after all, "anyone who makes money with us must follow our rules". That, in essence, is how state socialism has been dealing with foreign investors.

Before Hong Kong's handover to China, those who held anti-establishment views faced no issues working in Shenzhen or to set up their factories there. In recent years, however, even when Hong Kongers go to the mainland just to run an e-business, they have no choice but to be "defenders of the banner" and propagate the ideas in Xi Jinping's speeches, or else they would be snitched on. When economic activities and matters in the private domain can easily lead to trouble at every turn, the grey area of "one country, two systems" and the economic freedom thereof will only keep fading. When Beijing has already made up its mind and will never change its course, when it is bound to carry into destruction all the explicit and implicit systems that had made Hong Kong the success it was, what can we do?

Even if we are still a free economy today, we won't be far from extreme evil when economic life becomes dependent on "political correctness". The rise of the "yellow economic circle" or talk of protecting pro-protest businesses is more of a response to state corporatism. It aims to free Hong Kongers from dependence on the establishment and major corporate players. Without such freedom, there can be no sustainability, and everything would just be vain talk.

Various sectors are beginning to realise the importance of new trade unions. Partly because many of the existing trade unions have a vested interest in state corporatism, but also because "slashies" or multi-hyphenates of the gig economy are increasing in numbers. When these people form trade unions and support major corporate partners, it is a way to break free from the state's control.

As for the traditional leaders of the business community, they naturally have to sing China's "main melody" ostensibly, but they too are well aware of the impending problems. The Chinese state-owned enterprises' purchases of Hong Kong's strategic businesses are well known. The business leaders know they would become the targets of a political great purge should they fail to "recover" or "return" Hong Kong to Beijing. Just look at where their funds are flowing, and the words that come straight out of their hearts. They have already #WeConnect*.

* "We Connect", with the catchwords "We Care, We Listen, We Act" was Carrie Lam's campaign slogan during Hong Kong's Chief Executive's Election 2017.

This article was first published in Ming Pao.