How Vietnam is leveraging anti-China sentiments online

In this era of blossoming social media, anti-China sentiments have morphed and manifested online, compelling Vietnamese authorities to keep close tabs on it. ISEAS academic Dien Nguyen An Luong examines how the Vietnamese authorities have increasingly looked to social media to gauge anti-China sentiments and to calibrate their responses accordingly.

Anti-China sentiments have run deep in Vietnam, a country with bruising experiences of more than a thousand years of occupation, three deadly wars in the 1970s and 1980s and lingering tensions in the South China Sea with its giant next-door neighbour. This antipathy has barely wavered. In the State of Southeast Asia 2020 survey done by the ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute, Vietnamese respondents are those that registered the highest concerns about China's political, economic and strategic clout. China's Belt and Road Initiative has also been met with the highest sense of distrust in Vietnam.

In the era of blossoming social media, anti-China sentiments have morphed, evolved and manifested, compelling the authorities to keep close tabs on it. As Benedict Kerkvliet points out in Speaking Out in Vietnam: Public Political Criticism in a Communist Party-Ruled Nation, the real-life handling by Vietnamese authorities of public political criticism - anti-China sentiment included - can be characterised as a calibrated mixture of toleration, responsiveness and repression. This modus operandi appeared to be enforced on social media, as academic Giang Nguyen-Thu observes, Vietnam's online censorship playbook still more or less "adheres to the old model of mass media discipline".

State repression expressed on social media, in particular, has been mostly public opinion manipulations as manifested for example in encouraging "cyber troops to use their real accounts to spread pro-government propaganda, troll political dissidents, or mass-report content", according to a report written by researchers at Oxford University. Activists have accused Vietnam's 10,000-strong military cyber unit (dubbed Force 47) of making the most of loopholes in Facebook's community policies that allow for automatically pulling content if enough people lodge complaints about certain accounts.

Vietnam's leaders have been well aware that any move to repress growing anti-China sentiments could only further pit them against the public whose support they need to shore up.

Anti-China sentiments also take different forms and narratives, ranging from China-blaming to China-bashing to conspiracy theories to anti-globalism. Notably, while the authorities have mostly resorted to repression both in real life and on social media, they have increasingly shown signs of tolerating or even being responsive to different types of anti-China sentiments online.

These moves make sense for various reasons, chief among which is that, against the backdrop of China's growing assertiveness in the South China Sea and the global backlash it is facing, being cast as meek and kowtowing to Beijing at this time could make a serious dent in the career of any Vietnamese politician, and chip away at the legitimacy of the regime. Even in an authoritarian state like Vietnam, some measure of popular support is crucial to a regime's longevity. Indeed, responsiveness and legitimacy are all the more crucial to the resilience of regimes that are authoritarian. It is in this context that anti-China sentiments have found elbow room online - as long as they do not translate into real life protests, a spectre that has made social media a particular bête noire of Vietnamese authorities.

Vietnam's leaders have been well aware that any move to repress growing anti-China sentiments could only further pit them against the public whose support they need to shore up. In a country that prizes legitimacy and political stability above all else and is on the verge of a leadership transition, the authorities have increasingly looked to social media to gauge anti-China sentiments and to calibrate their responses accordingly.

The alliance between Facebook and anti-China sentiments

Facebook arrived in Vietnam in 2007 at the very moment when online activism was yearning for an alternative to the now-defunct Yahoo!360 social network. Social media-fueled anti-China protests started to broke out in late 2007 and early 2008 but were quickly repressed; physical force seemed to be the authorities' only solution back then. The alliance between Facebook and anti-China sentiments did not crystallise until 2009, when one of Vietnam's most revered national heroes stepped up to the plate.

Vo Nguyen Giap, a legendary and charismatic general, played an instrumental role in ousting French and American troops from the country. After retirement, he became a prominent critic of government policy and thinking. In 2009, Giap wrote letters to the government warning that two bauxite-mining developments in the offing would be detrimental to the environment, displace ethnic minority populations and threaten national security.

Under the deal, the government had awarded a Chinese firm the right to mine bauxite in the Central Highlands, a strategically important and sensitive region in Vietnam. In response to Giap's letters, the government gave reassurance that the country would not consider exploiting the mineral at "any cost".

Carl Thayer, an Australia-based veteran Vietnam analyst, pointed out that 2009 saw the organisation of disparate groups - Catholics, anti-China factions, environmentalists and democracy activists - "using Facebook as a rallying area for their shared opposition" to the bauxite mining agreement and to Vietnam's handling of China-related matters in general.

...those protests must have had the tacit approval from the authorities to go ahead in the first place.

In a country where the authorities have hardly brooked political demonstrations, anti-China protests, driven by Beijing's muscles-flexing moves in the South China Sea, broke out sporadically in the following decade. In 2011, after Chinese patrol boats attacked a Vietnamese oil survey off the coast of Vietnam, anti-Chinese protests took place every Sunday in Hanoi and Saigon for two months, before being suppressed by the authorities. In 2014, China's placement of an oil rig in Vietnam's exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea sparked deadly anti-China riots, plunging the two neighbours into their worst diplomatic crisis since the 1979 border war.

A pattern emerged: Even though they were all short-lived and eventually faced repression, those protests must have had the tacit approval from the authorities to go ahead in the first place. Such an approach was emblematic of the very fine line Hanoi has had to walk between appealing to an increasingly anti-China audience at home and avoiding overplaying the nationalism card with an eye on maintaining long-term bilateral relations with Beijing.

They also showed how nationalism merged with geopolitical thinking, and how territorial disputes were a trigger for such expressions of nationalism. But perhaps most importantly, those protests also corroborated the crucial role Facebook played in enabling activists to coalesce networks that only kept growing in the face of crackdowns.

Even though the bill did not single out China, those on the opposing camp interpreted it as a cudgel to offer preferential treatment to Chinese investors.

Social media is a major headache for the Vietnamese authorities not so much for the public criticism, but more so for its ability to fuel collective action or to organise protests. In a scathing 2013 opinion piece in the Communist Magazine, a Vietnamese military official warned about that role which social media could play, which he said should not be "underestimated". Despite such caveats, the authorities still apparently underestimated how activists could make the most of Facebook to organise street protests.

Nowhere was this more manifest than in the wave of anti-China demonstrations that rocked Vietnam in 2018. In the summer of that year, protesters took to the streets to march against a draft law that envisaged opening three special economic zones across Vietnam where foreign investors would be allowed to lease land for up to 99 years. Even though the bill did not single out China, those on the opposing camp interpreted it as a cudgel to offer preferential treatment to Chinese investors. The Vietnamese authorities eventually buckled under vociferous public pressure, and has put the draft law on the backburner indefinitely.

It would be a stretch, however, to use this result to accredit anti-China sentiments expressed online as a force driving Vietnam's policy and actions. Case in point: Vietnam's Cyber-Security Law, which was debated and scheduled for passage at the same time as the draft law on special economic zones, also stirred up fierce anti- China sentiments in 2018. In fact, the anti-China protests back then were driven by both pieces of legislation.

The Communist Party-dominated National Assembly, Vietnam's legislative body, eventually passed the Cyber-Security Law in the face of both international and domestic opposition.

The rationale for widespread protest against the Cyber-Security Law might have been even more obvious. It was being tabled at a time when Southeast Asian nations had almost jumped on the bandwagon of moving away from the Silicon Valley model allowing for greater freedom of expression and embraced China's state censorship approach. As with a similar Chinese law that was passed in late 2016, Vietnam's Cyber-Security Law seeks to give the government carte blanche to strictly police the Internet, scrutinise personal information, censor online discussion, and punish or even jail dissidents. The Communist Party-dominated National Assembly, Vietnam's legislative body, eventually passed the Cyber-Security Law in the face of both international and domestic opposition.

This leads to several intriguing questions: Even though a Vietnamese minister once reiterated that "there is no word that mentions China" in the draft law on special economic zones, why was it widely interpreted as being tailor-made for the Chinese? Who floated such an interpretation in the first place and for what purpose? Was the derailment of the bill the result of unfinished factional score-settling using anti-China sentiments as a smoke screen?

Still, the 2018 protests have been a bitter pill for the Vietnamese authorities to swallow. They left significant imprints on how the tools for dealing with anti-China sentiments are now designed.

Vietnam keeps revising online censorship playbook

Since 2019, the authorities have become acutely sensitive to and even accommodating of anti-China sentiments online, exemplified in two prominent examples. In October 2019, a film co-produced by DreamWorks and the Shanghai-based Pearl Studio was pulled out of Vietnamese cinemas for having a map that showed China's controversial nine-dash line. Less than a month later, the Hong Kong-born film star Jackie Chan had to cancel his charity visit to Vietnam after facing an online backlash for allegedly having spoken in support of the nine-dash line. These developments took place against the backdrop of a simmering stand-off, with a Chinese oil survey vessel having been in Vietnam's exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea since July 2019.

The pandemic has also seen the authorities finding an unlikely venue to boost their legitimacy, one that they once sought to repress: anti-China sentiments.

Then the Covid-19 pandemic broke out. By successfully pushing back the coronavirus, Vietnam's leadership has been able to earn the exceptional public support that it has been craving. The pandemic has also seen the authorities finding an unlikely venue to boost their legitimacy, one that they once sought to repress: anti-China sentiments. When the latest coronavirus wave hit Vietnam in late July, although officials did not explicitly link the new infections to Chinese nationals, the recurrence of the outbreak only exacerbated the already growing distrust of Beijing. How the Vietnamese authorities closely watched anti-China sentiments online and responded to it in the following days offer an interesting glimpse into what could have been Vietnam's constantly revised online censorship playbook.

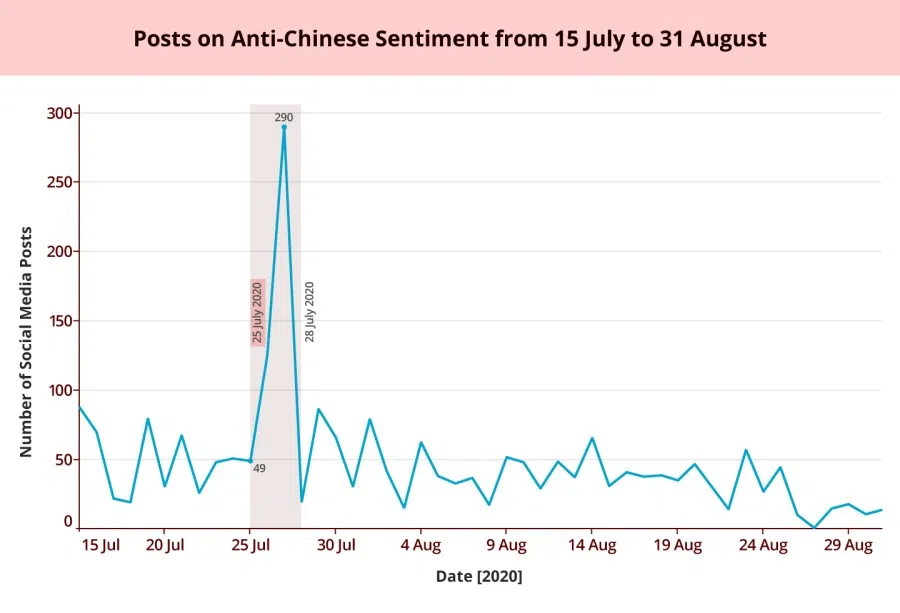

On 25 July, Vietnam's health authorities confirmed new Covid-19 cases in the central city of Da Nang, which had been virus-free for 99 days. On that very day, news of the arrest of a Chinese man involved in a ring allegedly smuggling Chinese nationals into Da Nang and neighbouring Quang Nam province sparked an online backlash. The number of social media posts with anti-Chinese sentiments skyrocketed to 290 on 27 July from just between 50 to less than 100 just days earlier.

One of the keywords that emerged with noticeable importance in social media posts was "Trung Cong cai", which refers to allegations that the Chinese Communists send their people to Vietnam to spread the virus.

In a country where the authorities have obliged all news outlets to censor readers' comments even on social media platforms, the appearance of hostile and disparaging anti-Chinese comments on the Facebook pages of some mainstream news sites are hard to ignore.

Cases in point: after news of the arrest of the Chinese man was posted on the official Facebook page of the Vietnamese government, it drew 17,000 reactions. Only 18 comments out of 1,400 were allowed to appear, but some of them contained strong words like "his face doesn't look like human", "send him to jail", or "beat him up". Notably, on the Facebook page of VTV24, a subsidiary of the state-run Vietnam Television, Internet users delivered even a more blistering anti-Chinese indictment. In a post of the same news that attracted 62,000 reactions and 9,900 comments (17 were published), netizens minced no words: "kill the bastards", "kill him at once", or "punish him with the highest penalty".

On the other hand, on the Facebook pages of other major news outlets like Tuoi Tre and VnExpress, no comments were shown on posts of the same news. Given how the Facebook pages of the government and Vietnam Television handled their readers' comments, the call made on the issue by Tuoi Tre and VnExpress seems to have been driven by self-censorship. This would have all the more made sense for Tuoi Tre, which must have learnt a hard lesson after its online version was suspended in 2018 partly because of comments deemed by the authorities as undermining "national unity". It remains unclear whether these comments are genuine or manufactured. What seems less questionable, however, was the fact that they were not subject to censorship.

...on 11 August, Vietnam released a documentary about the 1979 border war with China.

Realising how public perception would ebb and flow online, the authorities tried to make the most of that short burst of anti-China sentiments. Meanwhile, China's actions in the South China Sea had continued ruffling Vietnam's feathers since April. In mid-July, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo dismissed China's excessive maritime claims as "completely unlawful", a move that grabbed both global and regional headlines. Such a geopolitical context made it all the more ripe for Vietnam to ramp up its condemnation of what it perceived as China's aggressive moves in the South China Sea in just a matter of one month from late July to late August, even broaching again the possibility of suing Beijing.

In a yet quieter highly symbolic move, on 11 August, Vietnam released a documentary about the 1979 border war with China. The timing of releasing could not be more intriguing as it was pegged to an event that took place in February 1979.

The Communist Party-sanctioned documentary features a picture of China's paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, then the country's vice-president, bowing his head to Jimmy Carter, the American president. That was when Deng flew to Washington to seek the greenlight to send an estimated force of 600,000 Chinese troops to "teach Vietnam a lesson" for ousting the China-backed genocidal Khmer Rouge regime.

The takeaway here: by tapping into, albeit somehow quietly, anti-China sentiments online and seeking to accommodate it, Vietnam appears to show signs of appreciating its gaining of domestic legitimacy more highly than accommodating China, at least in the lead-up to the leadership transition early next year.

Who drives what?

How anti-China sentiments online were handled during the Covid-19 pandemic has become an increasingly crucial yardstick for the authorities to recalibrate their actions and telegraph objection to China's decisions. It remains a remote possibility, however, that anti-China sentiments online will become a force that can drive government's actions.

The authorities have been able to make the most of the combination of propaganda and anti-China sentiments to shape critical China-related coverage by the mainstream media. It is unlikely, however, that it can muster up enough political and technological muscles to do the same online any time soon. With Beijing not budging on its political hegemony, it will be worth watching how Vietnam continues playing the anti-China sentiment card, especially after the new leadership has been confirmed.

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2020/115 "How Hanoi is Leveraging Anti-China Sentiments Online" by Dien Nguyen An Luong. The writer would like to acknowledge the assistance of Benjamin Hu, Research Officer at the ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute, in developing the visualisation and analysing the data for this article.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)