Humanity needs to face the digital age as one family, not disparate warring tribes

Without a hitch, China has employed facial recognition technology and is developing a social credit system (data gathered by government and commercial platforms to grade how "good" and credit-worthy people are), trading off any risks for anticipated net societal benefit. The liberal West response could not be more different. The mere mention of surveillance triggers the nightmarish 1984 novel dystopian scenario of a police state. These divergent reactions have deep cultural roots.

In the West, the universe is divided into opposing spheres of good versus evil, light versus darkness, with the anticipated triumph of the former over the latter. The West social order reflects this antithesis, the private-public spheres, for example, are strictly dichotomised. Individuals are self-reliant entities, staking out an adversarial stance vis-à-vis the state. The American gun culture and anti-federalist sentiments are extensions of this factious ethos, feeding an underlying deep suspicion of any form of state surveillance.

Individual liberty anchored the 20th century global governance, inspiring the utopian vision of humanity inevitable "end of history" progress towards the full embrace of liberal democracy.

In Eastern cosmology, reality is the sum of complementary polarities: light and darkness, hot and cold, bound in a yin-yang coexistence. This is mirrored in the social milieu, where society at large is framed as family writ large. The self is integral to the whole, and the state, as would a paternal figure, oversees the good of all. Fiduciary trust undergirds the Confucian communitarian ethos, inculcating a more familial relationship between the citizenry and the state.

During the 1990s, these cultural dissonances dominated the human rights discourse. Together with the 1990 Cairo Declaration of Human Rights in Islam, the 1993 Bangkok Declaration pushed for an "Asian Values" interpretation of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), advocating a more communitarian rendition of rights.

These cross-cultural human rights debates marked humankind's first attempt to forge a unified norm. In the end, the Western worldview prevailed. Individual liberty anchored the 20th century global governance, inspiring the utopian vision of humanity inevitable "end of history" progress towards the full embrace of liberal democracy.

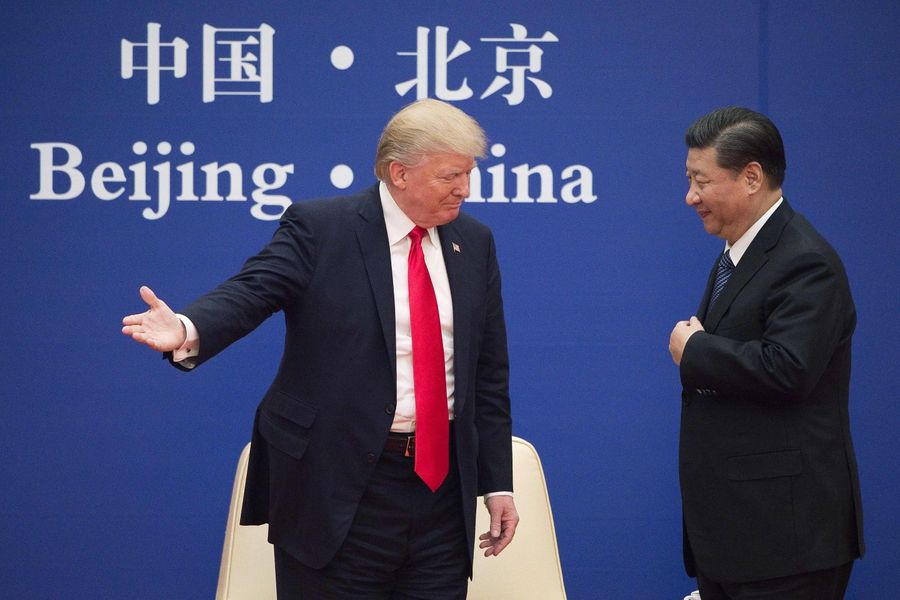

But China did not liberalise nor democratise as expected. And the Chinese one-party state is no ordinary outlier. By virtue of its size, China's illiberalism poses a serious challenge to the Western liberal model. Yet the message out of Beijing is coexistence rather than confrontation, and it will leave the US-led world order alone, unless provoked.

Modern China, like its imperial forebears, has no ambition to dictate global governance. The world is free to accept or reject the Chinese political system. In theory, if one chooses to engage the empire, then the "emperor" expects due homage, as in the tributary system of the past. However, the Middle Kingdom will refrain from meddling in the periphery states' domestic affairs. In the 21st century, this ancient tributary non-interference playbook is harder to sustain.

One cannot ignore the China system in a digital world

Unlike imperial China, modern China's power is no longer projected from behind the Great Wall. With the Belt and Road Initiative, the Chinese web is spreading globally. And these continental-maritime infrastructures networks are fast transiting into the digital phase with far-reaching transnational ramifications. Huawei's rolling out of the 5G network, for instance, has raised national security concerns. And as e-commerce giants like Alibaba penetrate the international online market, data collected in countries such as Malaysia and elsewhere, is likely to fall under Chinese jurisdiction. How Beijing legislates to protect personal information could well have implications beyond the mainland.

As in the biological sphere, a computer virus outbreak anywhere could trigger paralysis of the internet ecosystem everywhere. A digital equivalent of the World Health Organisation is needed to safeguard the world's cyber integrity.

Digital connectivity is compressing space into a seamless virtual reality, rendering geography irrelevant. The Hong Kong crisis, for instance, is challenging the ancient maxim "heaven is high and emperor is far way". The Great Firewall is not keeping China's cyber world within China. And based on the New York Times' recent investigative exposés on Xinjiang, the world is not being kept out of China either.

As the Covid-19 epidemic shows, difficulties in the mainland no longer stay within China. And with the advent of Industrial 4.0, humanity's fate will be even more intertwined. Encased in a digital bubble, our virtual well-being is inseparable from everyone else. As in the biological sphere, a computer virus outbreak anywhere could trigger paralysis of the internet ecosystem everywhere. A digital equivalent of the World Health Organisation is needed to safeguard the world's cyber integrity.

Yet in practice, Beijing has had to construct an alternate interface, alongside the current order.

In an apparent nod to these impending crises, President Xi Jinping has been extolling the vision of a "community of common destiny". Yet in practice, Beijing has had to construct an alternate interface, alongside the current order. This dual-track substitute sadly reflects the deep mistrust dividing the two great powers, and China's frustrated failure to become integrated into the existing American-led world order.

The PRC should be held accountable for its human rights record. But this can be done without the dogmatic imposition of Western values. The East possesses indigenous civilisational resources for self-reflection.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the US took the lead to rebuild the world. This period of the 20th century, also aptly named the American century, was an era of relative peace, allowing many countries, China included, to recover and prosper. Today, these countries are eager to help shape a more representative international system. But standing in their way is the same America who empowered them. A peculiar sense of exceptionalism is inhibiting the US's ability to envision any other order than its own.

The Chinese Communist Party regime is unlikely to turn liberal democratic any time soon and Washington must learn to live with it. That said, the Confucian communitarian ethos is not innately Orwellian. Like everybody else, the Chinese people cherish liberty and the Confucians affirm human dignity. And as with any other governments, the Chinese state wrestles with the "freedom and order" dialectic. And unfortunately, like anyone else, China at times fails to find the right balance, weighing on the side of social stability at a costly expense to individual liberty.

The big data privacy crisis is a global crisis - not made in China.

The PRC should be held accountable for its human rights record. But this can be done without the dogmatic imposition of Western values. The East possesses indigenous civilisational resources for self-reflection. China's political reform is best advanced by exhorting the Chinese to measure up to their own ideals.

China is neither a dystopian society nor the fount of global cyber-insecurity (read: Huawei). In fact, the US has been embroiled in information scandals such as Cambridge Analytica, Wikileaks, and Facebook. The big data privacy crisis is a global crisis - not made in China. Americans have got to stop projecting their Big Brother paranoia wholly onto the Chinese. The US must accept China as compatriots in addressing the digital challenges confronting humankind.

For its part, Beijing must work to ease the Eastern communitarianism and Western individualism tension. For some in the US, the fear is real: China's authoritarianism could pose an existential threat to their unique American way of life. Beijing can mitigate these anxieties by incorporating greater openness in its political culture.

The digital revolution is transforming the 21st century in unprecedented ways, and it is vital that the human race faces this new frontier as one family rather than as disparate warring tribes. By doing so, we stand a better chance to achieve harmonious coexistence, not only among ourselves but also with our increasingly ubiquitous digital companion, artificial intelligence (AI).