If they don't care about it, tear it down

NUS Head of Architecture Ho Puay-peng talks about his relationship with Hong Kong's elite, how Singapore lags behind Hong Kong, and why conservation is all about the views of the community.

Over 100 heritage sites in Hong Kong, including the hipster PMQ and Oil Street arts precincts, have a Singaporean to thank for their existence.

In his years of living and teaching in Hong Kong, architecture professor Ho Puay-peng was involved in shaping many conservation and urban development projects there. His travels across China also allowed him to learn more about the architecture in traditional villages and dive into the study of ancient Dunhuang cave artefacts and Buddhist literature - all of which informed his personal approach to architecture and conservation.

He had left Singapore in 1992 to teach architecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), a move that greatly indulged his interest in Chinese culture.

"Hong Kong generally shows more interest in Chinese culture and tradition. It is also near to the mainland, which makes it easier to study Chinese culture," says Prof Ho, who returned to Singapore two years ago to head the National University of Singapore's Department of Architecture in the School of Design and Environment. "Especially in the 1990s, Hong Kong's social and cultural climate, as well as its society's interest in history and the arts, were all ahead of Singapore."

His work put him in touch with the rich and famous, as well as their scions, who seek him out to protect and enhance their properties; he is on good terms with Hong Kong property developers such as Cheung Kong, New World, Sun Hung Kai and Hysan. On the other hand, when someone wants a heritage building demolished, they hope he doesn't catch wind of their intentions.

Even now, he is still an active advocate there: just last year, when approval was given to redevelop the Sham Shui Po property on which sits the headquarters of Garden Bakery, Hong Kong's first confectionery, Prof Ho wrote (unsuccessfully) to the local press to oppose the move.

Ever outspoken, always humorous, Prof Ho, whose father is Singapore's pioneer architect Ho Beng Hong (who designed the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Industry building), shares further insights on architecture and education here.

On how far he has gone to conserve a heritage site

Two words - Dragon Garden - sum up the lengths Prof Ho would go to to save a property for posterity.

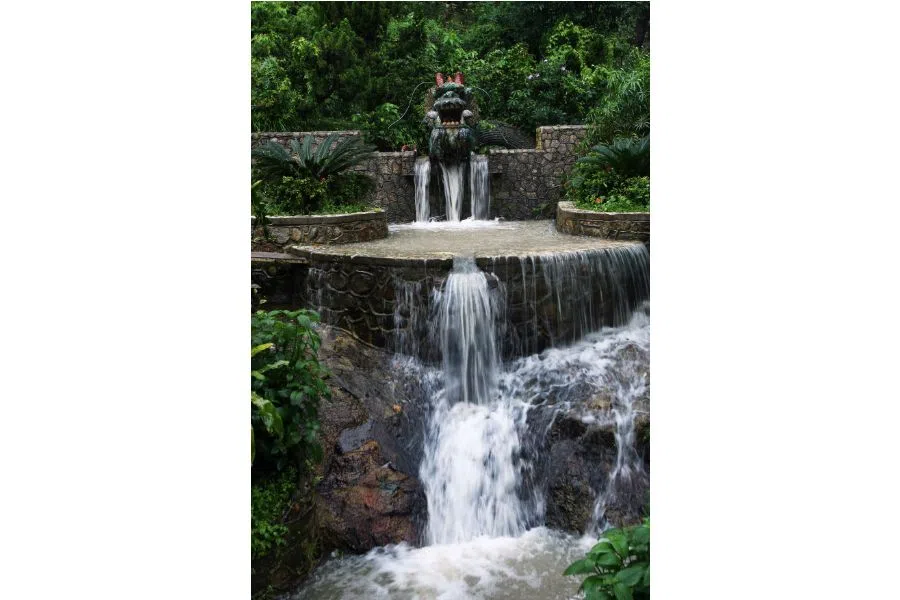

Dragon Garden was built in the 1950s, at a prime location with good feng shui on a hilltop facing the sea in Tsuen Wan. The private property was previously open to the public in the 1980s, and its Chinese style of classical grandeur formed the backdrop of movies featuring Bruce Lee and James Bond.

The owners, Dr and Mrs Lee Iu Cheung, ran the place for over 20 years, and were buried there upon their deaths. Dr Lee's grandson had no plans to keep the property in the family, however. Says Prof Ho: "He wanted to sell the place, dig up the coffins and send them to Shenzhen, and fill in the graves. No respect for the deceased."

The professor was then the Director of the Chinese University of Hong Kong's (CUHK) School of Architecture, and was invited around the year 2006 to be part of a family meeting to decide the fate of Dragon Garden. Given his penchant for old buildings and respect for their owners, as well as an admiration for all things antique, he spoke up strongly for conserving the place.

He explains at length the architectural and historical value of Dragon Garden, and how there were pavilions housing steles on either side of the graves, where stories about his grandfather were carved into the stone slabs.

But the grandson was unimpressed. "He said the workers were going to start levelling the graves at noon, so whatever we had to say, make it fast," says Prof Ho.

"I was forced into saying that I was not doing this for him or the people of Hong Kong, but for his grandfather. I asked him to think about what his late grandfather would think of him; I tried to frighten him with the thought of spirits haunting him! [laughs] But he still went ahead with the demolition. The steles were broken into pieces."

Prof Ho decided to pull out all stops, rallying fellow building conservationists to persuade interested developers not to buy and develop the site. The Hong Kong government also intervened. "In the end, one of the uncles bought the land. Except for the house and the pavilions, everything else was preserved. We also restored the graves of Dr Lee and his wife."

He says that as an architect in academia, all he can do to help conserve architecture is to try to get developers to see past the monetary value of buildings and recognise their humanistic and heritage value. "Generally, it is government buildings that are conserved. It is very difficult to have a private building conserved."

On Singapore's lack of building archives

Every nation should have detailed records of its historical buildings, whether there are intentions to preserve them or not.

Prof Ho emphasises the importance of building an open archive of architectural history, that should include images, photos, facts and modification history.

"Hong Kong has started to do all this, and Singapore has a lot to catch up on. Many buildings show no traces of their past and we are completely unaware of them, which is our loss. The good thing about Hong Kong is that it is very open and a lot of information is available online." Singapore has no such archive that is so open and transparent, he adds.

He feels that good documentation, archives and policies help with the process of national education. "If you are not transparent, you cannot teach, because there is no basis for discussion. It is an entire ecosystem." With more information available, "everyone will be interested, and pay attention and identify better with the buildings".

Hong Kong did not use to publish official assessments of buildings, keeping records only of national monuments. "But in the mid-1990s, Hong Kong conducted a survey of its buildings, which I was involved in," he explains. Two surveys later, it was decided that 1,444 buildings would be conserved, and another 70 buildings were later added to the list. Hong Kong's Antiquities Advisory Board followed up to determine which among those buildings were Grade I, II, or III heritage sites (with Grade I being the highest). These were disclosed more than 10 years ago.

Such assessments capture such values as a building's architectural and historical merit, significance to society, aesthetics, authenticity and rarity.

Hong Kong initially held off the publishing of such data for fear that once the buildings of less than Grade I value were made known, their owners may perceive their assets to be less deserving of conservation and be tempted to demolish them. "But since Hong Kong started publishing its building assessments, we have found that such concerns are unfounded," says Prof Ho.

On letting communities decide which buildings should stay

Which building ultimately deserves to be conserved depends very much on the will of the community it serves, and its ties with that community.

"Without the community's support, you cannot and need not preserve a building, because buildings are community assets, our legacy for the future," says Prof Ho. "This is about community ownership. If a building is conserved just for the sake of conservation, there's no point. Go ahead and tear it down, it doesn't matter. But if the community feels that a building has value, and the next generation needs a chance to understand that, then our generation has a duty to keep that building so that the next generation has a chance to decide for itself." In this area, Singaporeans should be encouraged to identify better with their architecture and have a say about which buildings they want to conserve, he adds.

On older versus younger generation and the value of speaking up

The situation was different in Hong Kong, where people are more opinionated and are less afraid to voice their wishes and preferences. He found this to be so when he was Dean at CUHK, where his students proved to be forthright and even provocative in their views.

He recounts that while he was a member of the Hong Kong Town Planning Board, there were plans to develop the area around New Territories, Sheung Shui and Fanling. Over 10,000 letters were received on the project, and about 3,000 people turned up in person for discussions. "The young people were strongly against the project. A woman in her 20s pointed at the lot of us who were in our 60s, and said loudly: 'You people already have one foot in the grave, what right do you have to decide our future?'"

If that sounded rude to him, Prof Ho does not show it. He says: "She had a point! The future should not be decided by us only, but by us together with them. We have experience, they have aspirations. To me, the Board is just one medium. And it is true we have one foot in the grave!" [laughs]

"Young people have their own thinking. As we plan for their future now, we really cannot impose our own thinking on them. So it is right that everyone decides together."

Prof Ho thinks Singapore undergrads could learn from their Hong Kong counterparts here. "University students in Singapore should be more proactive and responsible towards their own education. Many decisions can be made together with the students, not for them."

How does he practise this with his students? "I give them more say in choosing their subjects, especially in the Masters course. That way they have more ownership of their education. This approach is not common in Singapore.

"We teachers teach too much. I want to turn it around and provide a journey and experience of learning." Clearly, Prof Ho eschews passivity in his students. At the university orientation, for example, he finds the parents doing most of the legwork, not their children. "I don't want to talk to parents. I should be talking to their children. They're 18, 20 years old; do they need their parents to speak for them? There are many such cases in Singapore, but none in Hong Kong."

He recounts the memory of a mother at one of these orientations who questioned him non-stop about his courses while her child remained silent and uninquisitive. "I suggested that the parent join the class, since she was so interested!" he says, laughing. "It is important for students to be independent. Are kids in Singapore immature? Or are parents too aggressive?"

On that monastery

No chat with Prof Ho is complete without asking him about his magnum opus - Hong Kong business magnate Li Ka-shing's Tsz Shan Monastery. The 46,000-sq-m project in Tai Po was built over 10 years at a cost of HK$1.5 billion, and opened to the public in April 2015.

The project crystallises his expertise in Chinese architecture, Buddhist studies and Dunhuang studies.

Tsz Shan Monastery's key features include the 18-m-high Grand Buddha Hall, Universal Gate Hall, Great Vow Hall, Maitreya Hall, Tripitaka Library, and meditation hall, as well as a towering 76-m-high statue of the Goddess of Mercy, which is over twice as high as the giant Tian Tan Buddha statue on Lantau Island.

Prof Ho graduated from the faculty of architecture at the University of Edinburgh, and obtained his doctorate in Buddhist architecture and art from the University of London. He is the first doctoral candidate researching under Dunhuang expert Roderick Whitfield. It had always been Prof Ho's desire to see his seemingly unrelated fields of interest - of Buddhist culture, architectural history and art history - culminate in something greater than the sum of its parts.

As a Christian designing a Buddhist temple and creating sacred Buddhist figures, Prof Ho saw how to some extent, he could consider his faith, academia, and profession separately. "In the past few years, I have thought about the difference between faith, religion, and human spiritual pursuits. Right now I am keeping a bit of a distance from religion, and I am not thinking about faith."

Before embarking on the Tsz Shan Monastery project, he spent a long time in China's villages and towns, studying the architecture behind the abodes of officials and commoners in Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong. He was also involved in conservation work on residences and temples.

Buildings are where people live, it's people who are in there doing their thing. If you don't look at the link between buildings and people, and think of them as separate from the community, then buildings have no meaning.

He vividly recounts his experiences going into mountain villages with his CUHK colleagues. "We had anthropologists, historians, and architects among us. Everywhere we went, the anthropologists would go and talk to the temple attendants, the historians would look at inscriptions, and the architects would look at the buildings. At night we would gather and discuss how to put everything together." He found the piecing together of the different perspectives very fruitful.

He also found his conversations with the villagers enriching because, as he noted before, community matters to buildings. "Many people, when they do architectural history, they just stick to the buildings - how the roof is made, the structure and style of the building. I don't find that interesting. Buildings are where people live, it's people who are in there, doing their thing. If you don't look at the link between buildings and people, and think of them as separate from the community, then buildings have no meaning."

In designing Tsz Shan Monastery, Prof Ho was after a holistic human experience.

"How do people experience a temple setting? When we pass through a space, how do we feel the essence and teachings of Buddhism? The set-up of the space, the figurines, everything has to help us experience that. If it's designed just for prayer, it's not enough."

...if we think of architecture as a straight line with two extremes, with one end being the old way, and the other end is avant garde, going to either extreme is relatively easy. But if you want somewhere in between, that's more difficult.

The project took time because of the need to integrate the traditional and modern in the temple buildings in a way that would satisfy everybody.

"We had to convince Mr Li Ka-shing which was the best solution. I told him, if we think of architecture as a straight line with two extremes, with one end being the old way, and the other end is avant-garde, going to either extreme is relatively easy. But if you want somewhere in between, that's more difficult. How much is new? How much is traditional? What's the ratio? That process is tough. How do we decide? Because the final product is something discrete."

He gave the example of the traditional use of the dougong (a structural element in Chinese buildings, featuring interlocking wooden brackets) in large Chinese halls. But there is none under the roof of the monastery's great hall, because the framework of the building is steel, wrapped in African rosewood.

As Mr Li was a stickler for authenticity, the dougong had no place in this new fashion hybrid, "so we did away with it and put in windows instead", says Prof Ho. It proved to be a serendipitous decision - at night, light shines through the windows and the roof looks like it is floating above the building. A mesmerising sight.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao on 13 January 2019.