Is Indonesia's foreign policy tilting towards Beijing?

Earlier this month, two heavyweight Indonesian ministers visited Beijing. The visit by Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan and Minister for State-Owned Enterprises Erick Tohir is not the first high-level one between Indonesia and China and surely will not be the last.

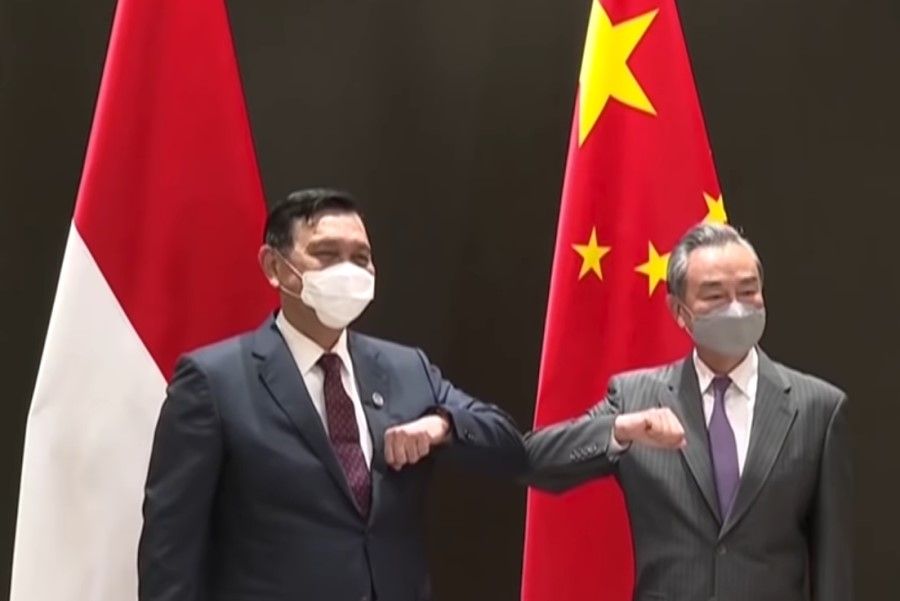

During the recent meeting between Luhut and Wang Yi, the Chinese foreign minister, Indonesia and China agreed to strengthen cooperation to tackle global and strategic challenges in the region. Some of the topics discussed during the meeting included politics, regional security, global health, the economy, investment, aeronautical issues and maritime cooperation. The meeting concluded with the signing of a memorandum of understanding establishing a High-Level Dialogue and Cooperation Mechanism (HDCM) between Indonesia and China. Minister Luhut and Foreign Minister Wang Yi will serve as the co-chairs of the mechanism.

The newly signed HDCM will further boost cooperation between Jakarta and Beijing. As Minister Tohir noted, Indonesia and China have implemented several important and strategic projects which involve Indonesian state-owned enterprises. These include two electricity projects and a fisheries investment in the eastern part of Indonesia. They are also working to establish Indonesia as a regional hub for Covid-19 vaccines and build up maritime infrastructure in Java and the eastern part of Indonesia.

China, with US$4.7 billion in investments, is currently the second-largest investor in Indonesia after Singapore. Beijing is also Jakarta's top trading partner.

There are also more concrete aspects to the relationship. Even before the pandemic started last year, Indonesia and China strengthened cooperation in many sectors, mainly on infrastructure projects through the Belt and Road Initiative, including the Jakarta-Bandung High-speed rail project that is expected to start operating in 2025. China has given Indonesia substantial Covid-19 assistance and helped Jakarta with the salvage of the sunken KRI Nanggala submarine in the northern part of Bali. China, with US$4.7 billion in investments, is currently the second-largest investor in Indonesia after Singapore. Beijing is also Jakarta's top trading partner.

There is some rationale behind the deeper relationship. Since President Joko Widodo's arrival in office in 2014, he has sought to create a well-grounded foreign policy. While he wants Indonesian foreign policy to be symbolic and formalistic, he also wants it to bring tangible benefits for the Indonesian people. That is why he often emphasises that Indonesian diplomats abroad should become salespeople for the country, selling Indonesian products seeking to attract foreign investors to the country.

Such a foreign policy is certainly laudable, as applied to Jakarta's relationship with China. Djauhari Oratmangun, Indonesia's ambassador to China, has been deployed since his appointment by the president in February 2018. Recently, President Widodo recalled Muhammad Luthfi, the Indonesian ambassador to the US, to serve as the Minister of Trade. As a result, Indonesia does not have an ambassador to Washington. Granted, Jakarta's deployment of diplomats to Beijing and Washington is merely one component of Indonesia's relationship with the two great powers; that said, the current imbalance is telling.

The tilt towards Beijing, fueled as it is by transactional and economic considerations, has also put Indonesia in an awkward position amidst the growing Sino-U.S. rivalry in the region.

The tilt towards Beijing, fuelled as it is by transactional and economic considerations, has also put Indonesia in an awkward position amidst the growing Sino-US rivalry in the region. Like many ASEAN member states, Indonesia has emphasised that it will not choose between the US and China. With some Indonesian leadership, ASEAN published its Outlook on the Indo Pacific document in 2019. The document effectively sought to reiterate the grouping's neutral position by omitting explicit support for the US-led free and open Indo-Pacific strategy, seen by many analysts as a subtle counter to China.

This is where Indonesia's "free and active" foreign policy comes in. "Free" refers to Jakarta not choosing a side among world powers, and "active" refers to Indonesia seeking to play a proactive (against passive) position in settling international issues. As Indonesia continues to pursue enhanced relations with China, it has also sought to deepen ties with other major powers such as the US and Japan. Last year some of Indonesia's key ministers such as Luhut and Prabowo Subianto visited Washington to discuss important issues such as defence and Covid-19 assistance. Indonesia has also strengthened its relations with Japan. Last October, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga visited Jakarta. Suga pledged 50 billion yen in Covid-19 assistance, the export of defence equipment and technology to Indonesia and agreed with President Jokowi to strengthen multilateral cooperation amid growing Sino-US rivalry. As Jusuf Wanandi has argued, the significance of the visit "goes far beyond bilateral relations; it also matters to the region and the world."

Indonesia's foreign policy should also be driven by ideals, shared values, and a consideration of the public interest. In practice, this means that Indonesia's enhanced relations with Beijing also come with substantial risks. For instance, many observers have criticised Indonesia - the largest Muslim country in the world - for its tepid response to the alleged human rights violations in Xinjiang to the minority Uighur Muslim ethnic group. Moeldoko, the Presidential Chief of Staff, had stated that China has "the sovereign right" to manage its own citizens and that "the Indonesian government will not meddle in the internal affairs of China."

Moreover, Indonesia also must remember that there have been many incidents in the North Natuna Sea in recent years because of China's illegal nine-dash line and provocations by the Chinese coast guard. Even though Indonesia and China do not have any pending or overlapping maritime boundaries, this remains a potential hotspot that might escalate at any time and threaten Indonesia's sovereign rights in the North Natuna Sea.

In short, Indonesia's foreign policy can be driven by economic interest and transactional considerations. But Jakarta should mind the gap in its approach to China, and also seek to balance its growing relationship with Beijing by pursuing deeper relations with other major powers with interests in the Indo-Pacific.

This article was first published by ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute as a Fulcrum commentary.

Related: Winning Indonesia over: US and China seek Indonesia's support in Southeast Asia | [South China Sea] Pandemic and US-Japan support reasons for Indonesia's strong stance on SCS | Indonesians welcome Chinese investment but fear influx of new Chinese migrants | Indonesia: Why China-funded companies are targeted by the anti-Jokowi camp | Indonesia crosses swords with China over South China Sea: 'Bombshell to stop China's expansionism'?