Is Laos mining itself into a crisis?

Attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) into its resource sectors has been integral to the Lao government's goal to leave the ranks of "Least Developed Countries". Having sustained average growth at more than 6% until the pandemic kicked in - with foreign grants and loans accounting for more than 20% of GDP - its socioeconomic development has been largely based on the extraction and export of the country's rich natural resources.

The state generates revenue through the export of hydropower, minerals, timber, and cash crops such as rubber and bananas. The mining sector, for instance, constitutes an estimated 20% of merchandise exports. However, the social and environmental costs of resource extraction constitute a key challenge to sustainable economic growth.

...economic opportunities contrast with considerable social and environmental costs.

This is particularly true for the Lao mining sector. As elsewhere in the world, extractive practices shape physical and social landscapes, altering local economies and human environment relations. In Laos, the important large-scale mining (LSM) areas are located in upland regions inhabited by peoples whose occupations are traditionally based on agriculture and forest products - livelihoods that are particularly vulnerable to the environmental impact of mining.

On the other hand, artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) provides local income opportunities, but sometimes contributes to land degradation and pollution which could also negatively affect the livelihoods (farming, fishing and livestock) of these communities.

Resource governance is thus a major concern for Lao state authorities. However, there is a lack of human and financial capacities as well as an institutional disconnect and internal struggles. These issues hamper the effective control of extractive industries, especially in Laos' rapidly changing mining sector.

The Lao mining sector

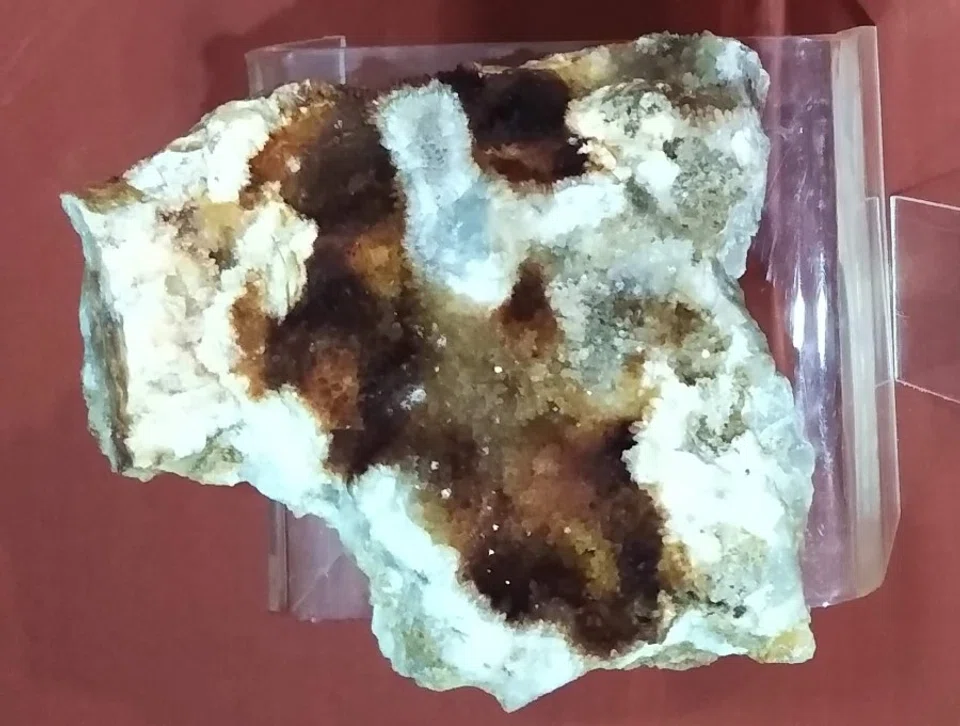

Since colonial times, Laos has earned considerable renown as a resource-rich frontier awaiting extraction and development. Gold reserves, in particular, attracted the attention of generations of entrepreneurs.

In the 1990s, the World Bank identified mining as a key sector for socioeconomic development and revenue generation. Since then, the mining sector has attracted a large share of FDI - especially from the regional powerhouses of China, Thailand and Vietnam. The Lao Ministry of Energy and Mines estimates more than 150 mineral reserves in the country, including gold, copper, tin, iron, bauxite, lignite and potash.

As in the case of the notorious hydropower dams mushrooming throughout the country, mining mostly happens in the culturally diverse upland areas that constitute 80% of Lao territory. The uplands of Laos appear as resource frontier to be developed and exploited. However, extraction can be both transformative and sometimes devastating for local communities. In the mining sector, economic opportunities contrast with considerable social and environmental costs.

The economic significance of industrial mining, however, does not always translate into job opportunities for the greater part of the local population.

The Lao mining sector used to be dominated by the "big two" gold and copper mining areas: the Phu Bia mine in Xaysomboun province and the Xepon mine in Savannakhet province. These mines were established by Australian mining companies after the World Bank-influenced economic policy reforms of the 1990s, and were later purchased by Chinese companies. Before the gradual closure of the copper mines during 2020 - as planned even before the pandemic for reasons of rentability - the Phu Bia and Xepon mines generated up to 90% of state revenues earned from mining. A number of smaller mining operations continue to explore the remaining gold reserves and other rare metals in these areas, taking advantage of existing infrastructures and new technologies.

Limited job opportunities for locals

The economic significance of industrial mining, however, does not always translate into job opportunities for the greater part of the local population. This can be partially attributed to the fact that the vast majority of mining concessions are operated by Chinese or Vietnamese investors. As in the case of Vietnamese-run rubber plantations in Laos, foreign mining companies prefer a Chinese and/or Vietnamese workforce, especially (but not only) with regard to skilled labour. The reason for this is manifold: for the companies, labour recruitment and control appear more convenient with work migrants from their respective countries.

Local villagers indeed often lack the skills for well-paid jobs and thus compete with migrants - from China/Vietnam, as well as from other Lao provinces - for unskilled jobs. Moreover, local villagers often prefer ASM over direct employment in the mines.

In the case of the tin mines in Khammouane - one of the first industries in colonial Laos - local villagers calculate the income from ASM against the low wages paid by Chinese and Vietnamese companies (even if according to the minimum wage - 1.2 million Kip/US$133 - as required by Lao Labour Law). However, while ASM "freelancers" might receive a higher income, they are excluded from the little work protection that formal mining labour guarantees.

Amidst reports of closure and fragmentation of the two big mines, alongside a growing and uncontrolled ASM sector, the latter has been receiving more political attention.

ASM practices have a long history in Laos. Early accounts of French explorers noted the panning and digging for alluvial minerals by Lao villagers. Indeed, even today an estimated 15% of the villages in Laos consider artisanal and small-scale mining an important component in their subsistence. In particular, agricultural slack periods are marked by increased ASM activity. And yet there are new dynamics and challenges such as increasing mechanisation, heterogeneous practices, transnational dynamics and resulting legal ambiguities.

The 'Law on Minerals' and its limitations

The revised Law on Minerals considers the diverse social and environmental challenges of mining. The legislative framework appears deliberate and robust, but certain limits to sound law enforcement remain. Most notably, there still exist insufficient monitoring capacities in relevant institutions like the Ministry of Energy and Mines, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, and the Ministry of Planning and Investment, along with the lack of communication between them and the respective national, provincial and district levels.

The coexistence and blurred boundaries between ASM and LSM have also impeded clear legal solutions. In many longstanding mining areas, artisanal and small-scale miners operate next to or within (foreign) LSM concessions. Even if benefitting from income opportunities in this legal grey zone, local communities bear the social and environmental costs of mining. This situation calls for specific sustainable solutions for governance and control.

The inclusion of ASM into the Law on Minerals is certainly an important step towards a more holistic view on mining and its corresponding economic practices and impact on livelihoods. For example, artisanal mining as a (legitimate) business "means mineral extraction activity by using primitive tools, mechanised equipment with fewer than five horsepower and no more than ten labourers" while small-scale mining is restricted to "stripping of top soil and overburden (...) where it is not appropriate for industrial mining within an area not to exceed ten hectares". Moreover, any ASM activity is only permitted for Lao citizens/entities.

Such narrow definitions make it difficult to legally reckon with recent trends of mechanisation, intensification in ASM, and the rise of (domestic and foreign) small-to-medium-scale mining activities that escape such categorisations. Many mining operations in Laos below the relatively well-monitored LSM level thus navigate in legally ambiguous waters. Increased mechanisation, migration and other unintended effects of mining development entail a variegated pattern of ASM in Laos which poses considerable challenges for effective legislation and governance.

ASM miners are tolerated by Chinese and Vietnamese companies under the condition that they sell the ore to them.

Conflicts between locals and foreign firms over allocated land

Another problem for resource governance are concessions that were granted before recent legal adjustments which sometimes overlap with village land or legitimate ASM claims. As in the case of agribusiness in Laos, foreign investors sometimes find their allocated land being smaller than the areas initially granted in contracts with the Lao state. Investors and villagers thus find themselves in awkward situations where they are left alone by Lao authorities to sort out their conflicting claims on the ground. The high number of opportunity-seeking Chinese entrepreneurs - activated by Chinese foreign investment incentives and the "empty land" discourse of the government of Laos, are likely to entail more of such conflicts.

In the case of the old tin mining area in the Nam Phathaen valley (Khammouane province), LSM and ASM entertain a complex coexistence. In some cases, ASM miners are tolerated by Chinese and Vietnamese companies under the condition that they sell the ore to them. As mentioned above, ASM provides a higher income for the villagers than the wage labour from Chinese and Vietnamese mines (besides the de facto exclusion of local Lao from permanent employment). For the companies, the local villagers represent an informal workforce for which they can deny any legal responsibility in case of accidents and other health risks. Moreover, farmland is increasingly degraded as explorations continue without proper enforcement of post-closure rehabilitation, despite it being required under the Law on Minerals.

Even though the Lao government has suspended new concessions, existing concessions are sometimes operated by incompetent mining companies. Regulatory frameworks and management capacities are still insufficient. The fragmentation of the big mining areas will put additional strain on the Lao authorities' already overtaxed capacities to control and monitor mining projects in the country. The question remains on how far local authorities are able or willing to use rules, regulations, and their power to effectively protect local resources and livelihoods from the impact of mining practices.

Violence directed against Chinese mining companies have been reported in recent years.

The social and environmental costs of mining

Communities living in mining areas in Laos often find themselves caught in a vicious cycle: extractive industries provide the opportunity of potential wealth that also undermines local livelihoods dependent on natural resources. In particular, industrial mining activities provide few job opportunities for local populations but have severe environmental impact on land and water resources. Land degradation drives people even more into ASM, ironically contributing to further environmental problems characterised by precarious livelihoods and health risks. Yet, villages in Laos have different experiences with regard to extractivism and the resulting dialectic of opportunity and precarity.

Academic Éric Mottet (2013) has shown how an ethnic Khmu village near the Phu Bia mine became an example of a village that benefited from the nearby mine through income opportunities (sale of agricultural produce to the mine) and the financing of local school and health services.

In contrast, a neighbouring Hmong village mainly experienced negative effects such as pollution and degradation of forest resources that are central to their livelihoods. Such experiences add to historical grievances and tensions between the Lao state and Hmong communities in Xaysomboun province. Violence directed against Chinese mining companies have been reported in recent years.

These impoverished households with little capital are dependent on these increasingly degraded natural resources for their subsistence, yet they benefit less from such mining opportunities.

This question of exclusion and vulnerability, especially for ethnic minority groups, becomes a crucial one for the ASM sector as well. Researcher Oulavanh Keovilignavong gives examples of how income opportunities through ASM are thwarted by the continuous degradation of land, water and forest resources. The effect of such degradation is particularly dramatic for poor households (often resettled ethnic minorities). These impoverished households with little capital are dependent on these increasingly degraded natural resources for their subsistence, yet they benefit less from such mining opportunities. Thus, both economic opportunities and risks through mining activities are unevenly distributed. Oulavanh's emphasis on the convergence of poverty and ethnic minority status points at a general problem in the upland valleys of Laos.

In the Nam Phathaen valley, Lao villagers combine agricultural subsistence with ASM activities, either in abandoned mines (some dating back to French colonial times) or on concession grounds. Land degradation has gradually shifted the ratio such that ASM presently comprises 70% of household incomes. Polluted water reserves require the villagers to buy fish and drinking water. Income opportunities are thus challenged by changing patterns of agricultural production and consumption. Women, in particular, carry a huge workload and health risks, as they manage both domestic labour and various ASM activities (such as panning in contaminated rivers).

This emerging field draws in workers, operators and investors from China and Vietnam who negotiate permissions with local authorities, usually without any governmental control or monitoring.

The problematic medium-scale mining operations

As academic Keith Barney notes, the recent decade has witnessed another environmentally detrimental development - medium-scale mechanised mining operating with backhoe excavators, pump dredges and sluices that blur the boundaries between LSM and ASM as stated in the Law on Minerals. This emerging field draws in workers, operators and investors from China and Vietnam who negotiate permissions with local authorities, usually without any governmental control or monitoring. Local villagers lease farm land to such mining operators for some easy money but then see their land being irreparably damaged and degraded.

The legal ambiguities of medium-scale operations in remote areas have devastating environmental consequences. Given that the monitoring capacities of the respective government agencies depend on mining-related state revenues or even directly from the mines as in the case of the (currently out-phasing) big Phu Bia and Xepon mines, the prospects of resource governance in the mining sector appear bleak. The growing fragmentation and complexity of the mining sector will yield less revenue for the Lao state but increase environmental risks and, thus, severely challenge local livelihoods.

Environmentalists in Laos (and neighbouring Thailand) are also concerned about the Hongsa lignite coal plant and mining project in Xayaboury province. The project is 80% Thai-owned and its 1878 MW electricity generation will be mainly exported to Thailand. Mining activities and related infrastructure development have affected forest and water resources. A coal-fired power project, the Hongsa plant contributes to climate change and local health risks. If we take a look from the ground, things get more complex and reveal the challenges of resource governance and local participation in contemporary Lao PDR.

Instead, they generate income through leasing land and/or selling agricultural produce to mining companies, or by practising ASM on tailings or in abandoned mines.

Opportunities and risks involved in mining in Laos

Laos remains a "frontier of economic opportunity" as the Asian Development Bank once exclaimed. However, the mining sector has in recent years lost its attractiveness to investors due to a global commodity price slump, depleting mineral ores, and incoherent legal regulations. Lockdowns during the pandemic have aggravated the situation.

Local communities rarely benefit from job opportunities in mining. Instead, they generate income through leasing land and/or selling agricultural produce to mining companies, or by practising ASM on tailings or in abandoned mines. ASM activities can be expected to increase during the pandemic due to economic downturn and the resulting land pressure as urbanites and migrants return to the villages.

Economic opportunities from mining come at high social and environmental costs for local communities: land and forest resources are degraded, while water reserves are polluted. This is due to ongoing contamination with heavy metals or destructions from increased mechanisation in small- and medium-scale mining practices that often escape governance. Post-closure mine rehabilitation is also weak. Covid-19 exacerbates existing vulnerabilities of ASM communities such as health risks, livelihood challenges, and social tensions (sometimes provoked by domestic in-migrants or returnees who have lost their jobs elsewhere).

That said, reliable resource governance is key to the protection of local livelihoods in regions affected by mining practices. Even if the Law on Minerals were refined to account for small- and medium-scale mining practices, implementation and enforcement remain a challenge. More capacities and financial means are needed to better monitor mine operation and rehabilitation. The participation of local communities in the entire process from granting concession to operation must be guaranteed - with responsible local authorities as a prerequisite.

In many mining areas, the degradation of agricultural and natural resources and the lack of alternative income and job opportunities have drawn more local villagers into ASM, creating a vicious cycle. The Lao authorities would need to provide better farmland rehabilitation to ensure agricultural livelihoods and upgrade people's skills to open up alternative job opportunities. As women and children involved in informal mining are particularly vulnerable, paying more political attention to the precarious livelihoods of ASM communities is the key to mitigating the social impact of mining in Laos.

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2021/44 "Artisanal, Small-scale and Large-scale Mining in Lao PDR" by Oliver Tappe.