Major powers react to rising Chinese influence in Mekong

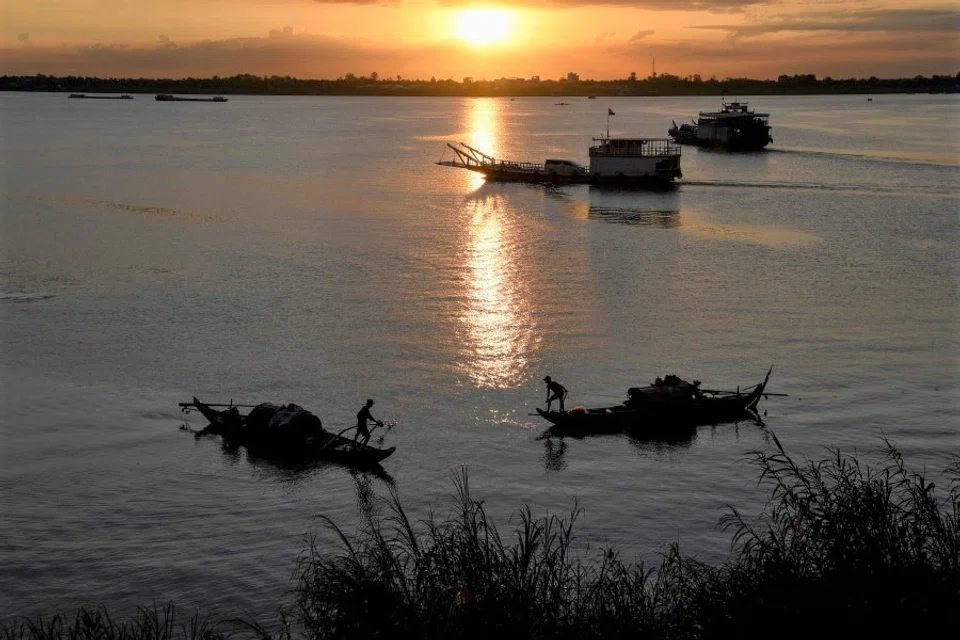

In the past three decades, Southeast Asia has been concerned with a strategic dilemma in maintaining a balance between the US and China. This concern takes place not only in maritime Southeast Asia, where the South China Sea disputes loom large. China's recently assertive role in the Mekong subregion also raises questions about Beijing's geostrategic intention in the continental part of the region. The establishment of the China-led subregional institution, known as the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC), has raised strategic suspicion about China's plan and influence in the region.

Powers such as the US, Japan and South Korea have become more proactive in enhancing their presence and significance in the region.

The academic literature on Southeast Asia's strategic thinking elaborates on the hedging strategy pursued by small- and medium-sized states in the region to manage regional order. In pursuing such a strategy, regional countries reach out to external powers such as the US, China, Australia, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia, and the EU to pursue not only security cooperation but also to deepen economic engagement. The purpose of this two-pronged strategy is to prevent the dominance of any power while creating economic interdependence and reaping benefits from cooperation.

Hedging through economic enmeshment, nevertheless, gives the impression that smaller powers in Southeast Asia are actively chasing after bigger powers for aid and favour. The effectiveness of such an enmeshment strategy rests mainly on the latter allowing things to happen. Their success depends mainly on these smaller powers not being viewed as a threat to the great powers. Despite that general conclusion, there is a condition under which such one-way enmeshment needs to be re-examined.

Currently, the strategic trend seems to be led by certain regional powers instead. Powers such as the US, Japan and South Korea have become more proactive in enhancing their presence and significance in the region. The Mekong subregion is one of the crucial areas where this phenomenon can be observed. This article examines this emerging reverse direction of engagement.

China's influence has created a paradoxical situation

China's recent proactive turn in mainland Southeast Asia is a driving force behind the current re-enmeshment by other regional powers. All mainland Southeast Asian nations maintain good ties with China despite Vietnam and China having ongoing maritime disputes. Good ties with Beijing offer avenues to economic and political stability. China also becomes an alternative source for market access, investment, and new technology. This is important for the less developed ASEAN member states in mainland Southeast Asia whose experiences in the market economy are relatively recent, and whose resources for upgrading their economies are limited. China has thus emerged as a top trading and investment partner for these economies in recent years.

Mainland Southeast Asia is also a part of the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor (CIPEC) within China's larger Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI). China's presence has risen along with its infrastructure development projects in the region, including the Kunming-Vientiane high-speed railway in Laos, the Thai-Chinese high-speed railway, the Kyaukpau seaport in Myanmar, and various projects in Cambodia, as well as the East Coast Rail Link in Malaysia.

China's increasing role and influence drives strategic competition in the region among regional powers. This situation will complicate Southeast Asia's ability to pursue an effective hedging strategy.

China's leading role is also buttressed by its ability to build a minilateral institution in the subregion. The Beijing-led LMC was established in 2014 encompassing China and all the nations in the Mekong subregion. The initiative aims to not only support economic development but also to strengthen security cooperation. In this connection, China pledged US$300 million under the LMC Special Fund to support the initial five-year plans. But whilst China reiterates LMC's support for ASEAN's community building, the LMC may likely draw the subregion away from ASEAN.

This leads to a paradoxical situation. On the one hand, China's increasing role and influence drives strategic competition in the region among regional powers. This situation will complicate Southeast Asia's ability to pursue an effective hedging strategy. On the other, the intensifying strategic competition is also renewing interest among major stakeholders to further engage mainland Southeast Asia. If this second trend is managed well, it will help offer options for mainland Southeast Asia's socio-economic development, hence restoring some balance to China's predominance.

Arguably, Trump's Indo-Pacific concept adds to the momentum of the re-engagement of the external powers in the Mekong subregion.

External powers re-engaging mainland Southeast Asia

This new round of engagement has been led by three powers - the US, Japan, and South Korea. Although they have had different levels of engagement with the region earlier, the round of re-enmeshment is mainly triggered by China's attempt to write a new institutional rule through the LMC, and more broadly, the BRI. The strategic outcome of various moves by these three seems to be harmonised despite their separate mechanism and policy objectives. Arguably, Trump's Indo-Pacific concept adds to the momentum of the re-engagement of the external powers in the Mekong subregion.

The US

The American presence in the region is an important factor amidst the ongoing major power adjustments. The US possesses various advantages stemming not only from its military might but also its economic strength and soft power. America has extensive security arrangements with most countries in Southeast Asia, both in security alliance and partnership.

However, US foreign policy towards Southeast Asia is inconsistent. This is even more the case where the subregion is concerned. Be that as it may, the region has seen a bit of the improvement in Washington's commitment in recent years especially following the introduction of the US Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy in 2018.

Pompeo: "I am sorry to report that we've seen some troubling trends. We see a spree of upstream dam-building which concentrates control over downstream flows... China operates extra-territorial river patrols. And we see a push to craft new Beijing-directed rules to govern the river..."

Within the FOIP, the Lower Mekong Initiative (LMI) has been reinvigorated as a tool for Washington's re-engagement with the subregion, even prior to 2018. In 2017, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson attended the 10th LMI Ministerial Meeting and proposed the "Mekong Water Data Initiative". This seeks to enhance the Mekong River Commission's capabilities to effectively share and use data on the Mekong river system for decision-making.

In 2018, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in the 11th LMI Ministerial Meeting, re-affirmed US commitment to LMI as a key driver for promoting connectivity, economic integration, sustainable development, and good governance. Pompeo's statement in the following meeting in 2019 was more strident in singling out China. He openly criticised China and the negative impact of its infrastructure projects in the Mekong subregion, especially on the environment and on water management. In Pompeo's words: "I am sorry to report that we've seen some troubling trends. We see a spree of upstream dam-building which concentrates control over downstream flows... China operates extra-territorial river patrols. And we see a push to craft new Beijing-directed rules to govern the river..."

He also promised initial funding of US$45 million for various LMI projects to improve people's quality of life in the subregion, such as education and English language training, clean drinking water, sanitation, better infrastructure, and environmental sustainability.

More recently, in December 2019, the US-sponsored LMI Annual Scientific Symposium was held in Yangon to seek innovative solutions to cross-border environmental and health challenges. The US has further offered an annual seed grant of up to US$15,000 for collaborative research projects. It has plans for additional financial support for other planned activities, for example, US$14 million to counter transnational crimes, for a conference on rules-based governance of trans-boundary rivers, a Mekong water data-sharing platform, and a new LMI public impact programme.

More importantly, the LMI provides a platform to bring in Japan, South Korea, and other stakeholders to collaborate on joint projects. For instance, the US partners with Japan to provide US$29.5 million for the development of regional electricity grids. It is funding a project with South Korea on satellite imagery to improve flood and drought patterns assessment in the Mekong basin. America also supports Thailand's recent idea to use the Ayeyawady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS) as a platform to coordinate projects related to rural development and capacity building.

Japan

Japan has played an essential role in the Mekong subregion since the end of the Cold War, both through its bilateral overseas development assistance (ODA) and regional organisations such as ASEAN and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The Japan-Mekong Region Partnership Program in 2007 formalised Japan's engagement with the entire subregion and annual high-level meetings were regularised. In 2009, the first leaders' summit adopted the Tokyo Declaration to establish "A New Partnership for the Common Flourishing Future" between Japan and the Mekong region. This commitment was renewed in 2012 into Tokyo Strategy for Mekong-Japan Cooperation in 2012.

Japan views that "the Mekong subregion, linking the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, has the geographical advantage of receiving considerable benefits from the realization of a free and open Indo-Pacific".

In recent years, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has rebooted Japan-Mekong relations through updating its Tokyo Strategy. In the 7th Mekong-Japan Summit Meeting in mid-2015, Japan pledged approximately US$7 million in ODA between 2016-2018. It also committed US$110 billion under its Tokyo Strategy 2015 to develop high-quality infrastructure development. Japan's action took place around the time China embarked on the BRI in 2014 and prepared to form the LMC sometime between the 17th ASEAN-China Summit in November 2014 and the first LMC ministerial meeting in November 2015.

In 2018, Japan updated its Tokyo Strategy during the 10th Mekong-Japan Summit on 9 October 2018. Both parties agreed to elevate their relations to a strategic partnership. This move demonstrates Japan's stronger commitment to the subregion, especially in sustainable development and connectivity.

Also, Tokyo Strategy 2018 reflects Japan's intention to synergise its role and policy with other existing mechanisms, especially America's FOIP. In Japan's view, "the Mekong subregion, linking the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, has the geographical advantage of receiving considerable benefits from the realisation of a free and open Indo-Pacific". Prime Minister Abe re-affirmed this stance at his meeting with US Vice President Pence in mid-November 2018. The Abe-Pence meeting highlights the two countries' common stance on the principle of fair rules in the economic development of a free and open Indo-Pacific in contrast to China's BRI. Both agreed to inject up to US$70 billion for infrastructure development in the Indo-Pacific region, especially on energy projects in Southeast Asia. Therefore, the Mekong subregion is further highlighted within this plan.

Not only does Japan cooperate with the US in expanding its presence in the Mekong, it also supports the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP). AOIP demonstrates ASEAN's effort in promoting cooperation amongst regional stakeholders by advocating inclusivity, transparency, rule-based regional architecture. In support of AOIP, Japan continues to promote regional connectivity and peace and stability in the Mekong.

Japan's longstanding role in economic development, trade, investment, and ODA are advantageous to its deeper engagement with the subregion.

Tokyo's commitment to the Mekong subregion is also found in its support of the existing subregional mechanism, especially ACMECS. In 2019, at the 11th Japan-Mekong Summit in Bangkok, Japan expressed its commitment to realise Sustainable Development Goals and FOIP through better coordination between Mekong-Japan Cooperation and ACMECS. As an ACMECS Development Partner, Japan pledged its support of ACMECS activities in various areas including energy, water resource management, human resource development, and people-to-people exchanges. Japan continues to promote its traditional approach to cooperation in Southeast Asia based on shared responsibility and consultation. It sees ACMECS as an appropriate venue for policy coordination between Japan's development assistance and the needs of the subregional countries.

Japan's longstanding role in economic development, trade, investment, and ODA are advantageous to its deeper engagement with the subregion. The acceptance of Japan's role can be gleaned from the views of Cambodia, which China regards as an "iron-clad" friend. Cambodia was the first ASEAN country to welcome Japan's FOIP version and "regards Japan as one of the key strategic and economic partners in its diversification and hedging strategy". The regional acceptance of Japan is a hallmark of its soft power in the Mekong subregion, which helps to improve the power equilibrium.

South Korea

South Korea has become more active in the subregion under President Moon Jae-in's New Southern Policy (NSP). The NSP reflects a strong economic linkage between South Korea and the subregion. Southeast Asia has also become an alternative location for South Korean FDI diversification, especially away from China. Statistics suggest that Korea's FDI in ASEAN has exceeded that in China since 2013. The South Korea-China tension over the deployment of the US Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system in 2016 further underscored the importance of Southeast Asia to Seoul.

... South Korea has boosted trade relations with Vietnam and the rest of Southeast Asia. Its exports to Vietnam jumped US$27.77 billion in 2015 to US$48.62 billion in 2018.

A key focus of the NSP is the Mekong subregion. The subregion offers a young demographic composition and abundant resources, which are a good combination for potential growth. In 2019, the average GDP growth in CLMV (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam) was around 6.5%, which outpaced those of older ASEAN member economies. Therefore, it is not surprising to see Southeast Asia, especially the Mekong subregion, having a higher priority in Seoul's current foreign policy. This is evident from the South Korean ODA contribution to the CLMV countries accounting for roughly one-fourth of its total ODA contribution in 2018.

President Moon kicked off his NSP in the subregion by visiting Vietnam in March 2018. This visit reflects South Korea's embedded economic interest in Vietnam. Vietnam received more than 90% of South Korea's FDI amongst CLMV countries, accounting for US$3,337.7 million out of US$3,427.9 million in 2017. To mitigate the impact of the Sino-US trade war, South Korea has boosted trade relations with Vietnam and the rest of Southeast Asia. Its exports to Vietnam jumped US$27.77 billion in 2015 to US$48.62 billion in 2018. This makes Vietnam South Korea's third export destination after China and the US.

In the following year, President Moon made a week-long tour on 1-6 September 2019 to the subregion, including Thailand, Myanmar, and Lao. During the trip, President Moon emphasised that South Korea could play a role in supporting the preparation for the fourth industrial revolution and human development. This tour highlighted South Korea's active outreach to the subregion in 2019 which culminated in the hosting of the ASEAN-ROK Commemorative Summit in Busan in November 2019.

At the summit, South Korea not only expressed a strong commitment to ASEAN but also emphasised the Mekong-ROK Cooperation as a platform for deepening its engagement. The Mekong-ROK Summit was also launched alongside for the first time. The cooperation mechanism had begun in 2011 with only ministerial and senior official meetings.

Seoul has recently shown its support of USFOIP in line with its New Southern Policy in the subregion. Korea certainly views the principle of openness and inclusivity promoted under the USFOIP to be beneficial to its economic interest.

The Mekong-ROK Summit outlined potential areas where South Korea will be able to support the subregion, including on water resources management and infrastructure development. Also, considering the CLMV countries having diplomatic ties with Pyongyang, South Korea also expects the subregion's support for the peace process in the Korean peninsula.

There also appears to be some form of policy alignment between South Korea and the US under the FOIP in the subregion. Seoul has recently shown its support of USFOIP in line with its NSP in the subregion. Korea certainly views the principle of openness and inclusivity promoted under the USFOIP to be beneficial to its economic interest. Apart from the aforementioned satellite imagery project, the collaboration between South Korea and the US-backed LMI is expected to increase.

Under its NSP, South Korea also backs Thailand-led ACMECS as reflected in its support of the ACMECS Master Plan (2019-2023) during the Mekong-ROK Cooperation. Similar to other stakeholders, South Korea agrees that better coordination in priority setting between the subregion and external donors will result in mutual benefits. Therefore, South Korea also became an ACMECS Development Partner and pledged to fund ACMECS projects to the tune of US$1 million annually. South Korea also supports Thailand's trilateral ODA arrangement between South Korea, Thailand, and third parties to provide capacity-building assistance to the developing countries, especially in Southeast Asia.

This renewed engagement by external powers benefits the Mekong Southeast Asian countries as it offers them more options to promote their economic development. However, maintaining a fine balance among the major powers especially between the US and China is a challenge.

Regional states to grapple with big power dynamics

Mainland Southeast Asia especially the Mekong subregion has become a site for renewed engagement by external powers. This trend is driven mainly by China's proactive foreign policy and its promotion of the BRI and LMC.

The US is at the frontline of this strategic competition, especially under the Indo-Pacific strategy. The reactivation of the LMI mechanism has become a policy tool specifically for the Mekong subregion. The US action has stimulated and facilitated other major regional players - Japan and South Korea - to strengthen and deepen their ties with the Mekong countries through their existing cooperative arrangements. The promotion of linkages among these different subregional arrangements stands in contrast to the LMC which focuses solely on binding China closer to the Mekong countries.

This renewed engagement by external powers benefits the Mekong Southeast Asian countries as it offers them more options to promote their economic development. However, maintaining a fine balance among the major powers especially between the US and China is a challenge. This task has become more difficult now when the confrontation is upfront and intensified.

The recent online battle between the US and Chinese Embassies in Bangkok is a case in point. The American Embassy carried its ambassador's op-ed article on its website which questions China's water control in the Mekong upstream. In response, the Chinese Embassy carried a rejoinder justifying why the drought and flood along the Mekong cannot be attributable to dams erected upstream in Yunnan Province. The regional states still need to grapple with big power dynamics and send a clear signal to external powers that increasing cooperation with them does not equate to choosing sides.

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2020/88 "Re-enmeshment in the Mekong: External Powers' Turn" by Pongphisoot Busbarat.