Marine science collaborations can help defuse tensions in the South China Sea

Rising tensions and a red horizon in the South China Sea are creating fear and grief among fishermen, who are often cast as maritime sentinels in the face of approaching storms. There are, however, hopeful signs of marine science cooperation in the region to address the clear and present danger from climate change, coral reef destruction, pollution and a collapsing fishery.

With environmental security shaping a new South China Sea conversation about ecological challenges, science cooperation represents a litmus test to link the impact of environmental change to both national and international security.

Paul Berkman, oceanographer and former head of the Arctic Ocean Geopolitics Programme at the Scott Polar Research Institute, provides a valuable definition of environmental security. "It's an integrated approach for assessing and responding to the risks as well as the opportunities generated by an environmental state-change."

Protecting marine environments and ensuring the ocean's sustainability is a global issue, and nowhere is this more critical than in the South China Sea...

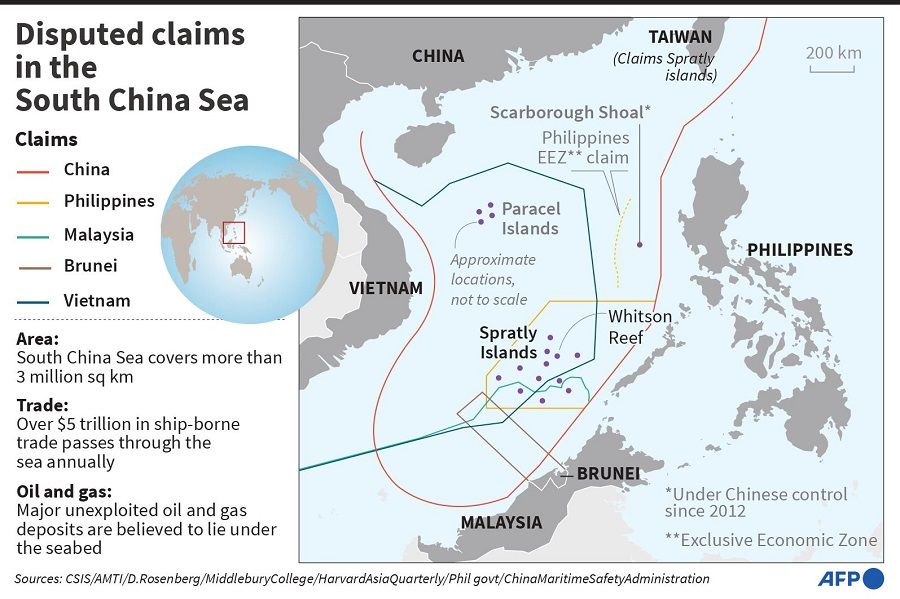

The Spratly Islands in the South China Sea are the focal point of a territorial dispute that represents a serious threat to regional security in Southeast Asia. Six governments - China, Vietnam, Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei - have all laid claims to all or some of the more than 230 islets, reefs and shoals in the Spratly area.

Protecting marine life in the South China Sea

Protecting marine environments and ensuring the ocean's sustainability is a global issue, and nowhere is this more critical than in the South China Sea, a body of water offering abundant and complex marine ecosystems for more than 400 million lives along the coastal areas.

The degradation of reefs that can be traced to reclamations and climate change translates into less fish to feed the increasing populations among all claimant nations. Fishermen sent by their governments to find food for their people discover themselves on the front lines of this ecological battle. This assault on the seascape includes the increasing level of environmental pollution from land, ships, and oil and gas offshore platforms.

It was five years ago that an international tribunal in a landmark ruling declared that China "had caused severe harm to the coral reef environment". While the decision was an indictment of Beijing's large-scale reclamation and construction of artificial islands, it has created novel shifts in conversations and science workshops in building cooperation for managing maritime resources.

The impact of continuous coastal development, reclamations, fishery collapses and increased maritime traffic has brought about a rising chorus of scientists in the region and from outside, who view the sea as an ideal platform for promoting regional cooperation and for using the ocean as a natural laboratory.

The immense biodiversity that exists in the South China Sea cannot be ignored. The impact of continuous coastal development, reclamations, fishery collapses and increased maritime traffic has brought about a rising chorus of scientists in the region and from outside, who view the sea as an ideal platform for promoting regional cooperation and for using the ocean as a natural laboratory.

This body of water is home to one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on earth. It includes around 600 species of coral reef. Research reveals that marine protected areas or reserves provide protection of habitat and conservation of biodiversity. Marine reserves continue to emerge as a tool to reverse or prevent the decline of these fragile ecosystems.

Feasibility of an international peace park

Professor John McManus, a marine biologist at the University of Miami and a notable coral reef specialist has conducted research in the Spratly Islands for more than a quarter of a century. He knows that the most important resource in these heavily fished waters is the larvae of fish and invertebrates. As a result, he has called repeatedly for the development of an international peace park in this contested region.

"Given the rapid proliferation of international peace parks around the world, it is now time to take positive steps toward the establishment of a Spratly Islands Marine Peace Park," claims McManus.

The marriage of policy and science is essential to navigating these perilous geopolitical waters.

Marine biologists, who share a common language that cuts across political, economic and social differences, recognise that the structure of a coral reef is strewn with the detritus of perpetual conflict and represents one of nature's cruelest battlefields.

Policymakers may do well to take a lesson or two from nature as they examine how best to address the complex and myriad of sovereignty claims through the lens of science. The marriage of policy and science is essential to navigating these perilous geopolitical waters.

Beginnings of ocean science cooperation

Dr. Yu Weidong from the School of Atmospheric Sciences at Sun Yat-sen University advocates for regional oceanographic cooperation. In an email response, he wrote, "I think the ocean science cooperation is the best way to move forward in collecting and stimulating the common interests to address the many challenges, including climate change, extreme weather and marine ecosystems."

His science-driven monsoon onset monitoring experience enabled him to work with international partners through the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission for the Western Pacific (IOC-Westpac) and drew participants from Myanmar, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam. This bodes well for sharing data from ocean observatories and for depoliticising ongoing pressures in the South China Sea.

While China is actively engaged and supportive of the UN Decade of Ocean Science (2021-2030), Beijing has been reluctant to participate in any substantive collaboration with Woods Hole Ocean Institute (WHOI). This geopolitical barrier is largely because WHOI has engaged in science surveys with Taiwan.

"Because of the current environment, I think it is difficult to get mainland China oceanographic institutes involved in this cooperation, including data sharing," claims Dr Zhaohui Wang, at WHOI.

Nevertheless, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Working Group on Coastal and Marine Environment recognises that the region faces enormous challenges to sustainability in coastal and shared ocean regions. Since it is the UN Decade of Ocean Science, their common interests are in close alignment in adopting a sustainable ecosystem approach that addresses transboundary marine areas.

Historically there have been a variety of scientific cooperative activities at bilateral and multilateral levels. This includes the Joint Oceanographic and Marine Scientific Research Expedition in the South China Sea (JOMSRE-SCS) from 1996-2007 and the Western Pacific Ocean System Project (WPOS) from 2014-2019.

To avoid an environmental catastrophe from unfolding in the region, encouraging signs were offered by China and Vietnam in their respective 2020 back-to-back international ocean governance programmes - China's symposium on "Maritime Cooperation and Ocean Governance" preceded Hanoi's initiative, "Maintaining Peace and Cooperation through Time of Turbulence".

The good news is that the Philippines and Vietnam have agreed to resume joint marine scientific research expeditions (JOMSRE) sometime in 2022. The two nations began collaborative science surveys between 1996 and 2007. The marine science collaboration led to four completed surveys that included studies of the biomass of fish species and coral reefs in the southern part of the South China Sea.

In March 2008, a decision to expand the number of participants and to open up the discussions with China failed. As a result, further science surveys were suspended and the JOMSRE Phase 2 plan ceased.

The stakes are high for all. Uncontrolled fishing pressure has caused depletion of fish stocks by 70-95% over the past three decades. This ecological disaster is further exacerbated by a looming coral reef collapse. Immediate steps must be now taken for joint management of fisheries and cooperative conservation and sustainability measures. These scientific experiences are much easier to achieve and they include biodiversity expeditions, as well as sea level and environmental monitoring.

...collaborative marine science efforts can contribute toward defusing the current tensions and militarisation in the region.

Marine science collaborations can defuse tensions

What is noteworthy is that collaborative marine science efforts can contribute toward defusing the current tensions and militarisation in the region.

Previous marine science workshop dialogues have produced cooperation between China and Vietnam on maritime delimitation in the Gulf of Tonkin and limited joint cooperation on fisheries in the area. It is also noteworthy that China established in 2011, the China-ASEAN Maritime Cooperation Fund, investing almost US$470 million for scientific surveys, environmental protection and maritime security and search and rescue.

Both the Center for Biological Diversity and the United Nations Environmental Programme warn that it could be a scary future indeed, with as many as 30-50% of all species possibly hurtling towards extinction by mid-century. Certainly, Beijing needs no reminder of how its coastal economic boom degraded, if not destroyed, the country's coastal marine ecosystems at an alarming rate over the past two decades.

Greg Poling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), believes that traditional and non-traditional security measures revealed in marine environmental protection, marine scientific research, navigation safety, and management of natural resources, are some of the central issues of the China-Southeast Asia Research Center on the South China Sea (CSARC).

Also, in early November, the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (CHD), held its first workshop on South China Sea Coastal States Cooperation. There, policy analysts and researchers from China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam engaged in conversations about confidence-building mechanisms in addressing cooperation on environmental protection, climate change and marine pollution.

For now, the tide may be lifting science-research surveys above the din of geopolitics and sovereignty claims.

Related: US and China not perceived as climate change leaders in Southeast Asia | American researcher: China's upstream dams threaten economy and security of Mekong region | Net-zero CO2 emissions before 2060: Is China's climate goal too ambitious? | Can China keep its climate change promises? | US-China competition in climate cooperation a good thing for Southeast Asia