[Photo story] Cherry blossoms are blooming in Wuhan, but is it spring yet?

Spring: the season of new beginnings. The earth reawakens after its winter sleep.

Animals come out of hibernation, or return from winter travels. Young animals are born. The ground softens as the air warms up again, and farmers and gardeners get busy planting their seeds for the next season.

Most of all, in the spring, fresh buds bloom, and the world resumes its colour.

One flower that is closely associated with spring is the cherry blossom, which is also most associated with Japan.

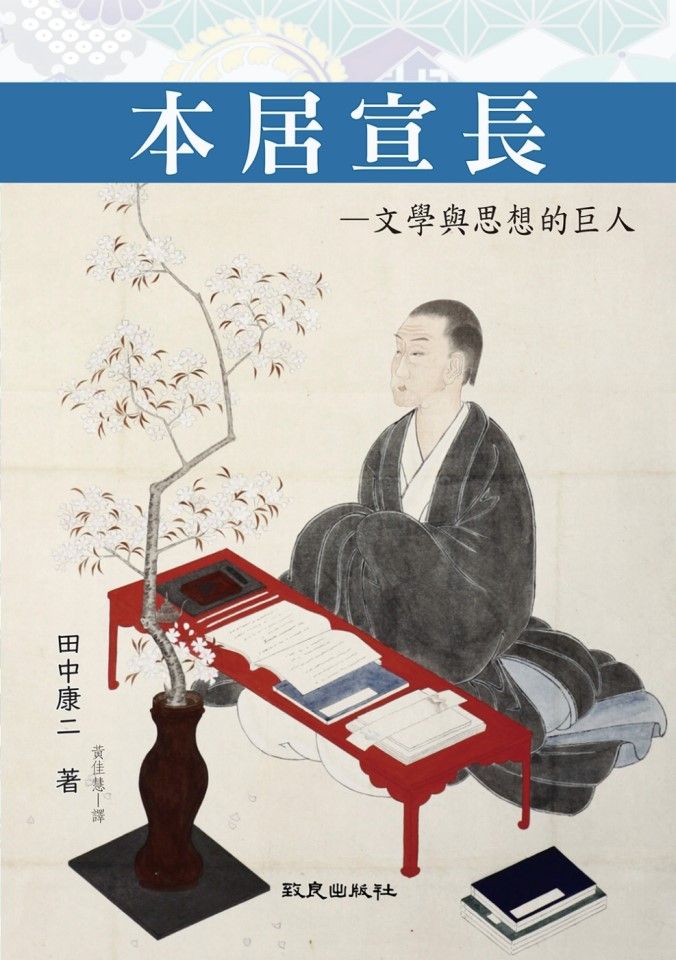

In Japan, cherry blossoms are a metaphor for the transience of life. This is embodied in the concept of mono no aware, literally "the pathos of things", or an awareness and gentle sadness at impermanence being the reality of life, which forms part of the Buddhist influence in Japanese culture. The association of the cherry blossom with mono no aware dates back to 18th century Edo period Japanese cultural scholar Motoori Norinaga, who drew on the concept in his literary criticism of The Tale of Genji.

In 1939, during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese army planted the first batch of cherry trees in Wuhan University (WHU), to relieve the homesickness of their troops.

The transient beauty of cherry blossoms is thus associated with mortality, which makes them richly symbolic.

During World War II, the cherry blossom was used to motivate and inspire nationalism among the Japanese people. Soldiers were likened to cherry blossoms; falling cherry petals came to represent the sacrifice of youth. Japanese pilots painted them on their planes on suicide missions.

But the cherry blossom also has been used for more peaceable ends.

In 1939, during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese army planted the first batch of cherry trees in Wuhan University (WHU), to relieve the homesickness of their troops. These trees were preserved after the war ended, despite their historical links.

Later, in 1972, to mark the normalisation of China-Japan relations, another batch of cherry trees was offered to Premier Zhou Enlai, who gave 20 trees to WHU. The WHU website describes subsequent donations in 1983 by biology professor Wang Mingquan, who studied in Kyoto, and by a Japanese delegation in 1992.

The WHU website also quotes assistant lecturer Tang Shanghao in 1985 ruminating about the first batch of cherry blossoms: "Though their origins trace back to the war period, these trees are innocent and grow uninhibitedly. In my eastward journey to Washington D.C. last month, I also witnessed the cherry blossoms flourishing in front of the White House. At the end of the day, beauty itself is borderless."

Usually, WHU hosts hordes of visitors in March, who go there just to admire the blossoms.

This year, of course, is very different. Wuhan is the epicentre of the Covid-19 coronavirus outbreak, which has swept the globe.

With Wuhan still on lockdown and "social distancing" a new catchphrase in efforts to slow the spread of the coronavirus, this year WHU closed its grounds to general visitors. Enter 5G technology, as the university arranged for a live feed of the cherry blossoms instead.

Of course, Wuhan is not the only place in China to admire cherry blossoms.

In Beijing, there is Yuyuantan Park, which features some 2,000 trees and hosts the city's annual Cherry Blossoms Culture Festival. Unfortunately, this year's event has been called off due to the Covid-19 outbreak. The Summer Palace is also a popular site to see cherry blossoms, especially in early April. Notably, in the Summer Palace, other than cherry blossoms, there are also two magnolia trees planted by the Qianlong Emperor (1711-1799). One of them produces pink flowers and is found behind the Hall of Joy and Longevity (乐寿堂). The other produces white flowers and is located near Yaoyue Gate.

Other places to enjoy cherry blossoms include Zhongshan Park in Qingdao, with its famous Cherry Blossom Road lined with more than 20,000 trees, best seen in mid-April. Cherry trees are also found in Shanghai, Hangzhou, Dalian, and Guangzhou. Many of these parks are now open to the public, with crowd control measures in place.

In Japan, there is the tradition of hanami, or admiring flowers, specifically cherry blossoms. Hanami festivals are usually a major event in Japan, with a long history. The hanami tradition dates back many centuries; the eighth-century chronicle Nihon Shoki (日本書紀) records hanami festivals being held as early as the third century AD. The Japanese turn out in large numbers at parks, shrines, and temples, to eat and drink surrounded by cherry blossoms.

This year, with the Covid-19 outbreak, the Japanese government has called for large-scale events to be scrapped, postponed, or downsized to mitigate the risk of infections. Some municipalities have urged the cancellation of hanami parties. However, at least one municipality will carry on - Tokihiro Nakamura, governor of Shikoku's Ehime prefecture, said on 13 March that the prefecture will not call for the across-the-board cancellation of hanami parties.

The West, too, has its share of cherry blossoms, not least in Europe and the US.

In the winter of 1909, the mayor of Tokyo sent 2,000 young cherry trees to Washington. However, they were found to be infested with insects, and were burned by entomologists from the US Department of Agriculture. Japan then sent a second batch of 3,020 trees in 1912. In a ceremony in Washington D.C on 27 March 1912, US First Lady Helen Herron Taft and Viscountess Chinda, wife of the Japanese ambassador, planted the first two trees on the northern bank of the Tidal Basin, near what is now Independence Avenue Southwest. A plaque marks where these two trees still stand, at the terminus of 17th Street Southwest, near the John Paul Jones Memorial.

The other trees lined the bank of the Tidal Basin in West Potomac Park, and the road in East Potomac Park in Washington, D.C. They are a popular tourist attraction today, and are celebrated at the annual National Cherry Blossom Festival. Japan then gave another 3,800 trees to the US in 1965.

Japan has also given trees to countries such as Canada and Germany, which have become symbols of goodwill. In 1990, Japan donated about 9,000 trees to Germany, to be planted along sections of what used to be the Berlin Wall, in appreciation of German reunification. The gift was supported by donations from the Japanese people. Today, the "Mauer Weg", the trail where the Berlin Wall once stood, features stretches of "cherry blossom avenues".

As spring exerts its warmth and the Covid-19 outbreak gradually comes under control in China, life is slowly going back to normal. Following the lockdown on Wuhan, other quarantine measures - which have lasted about two months - are gradually being eased, with people going back to work and school.

Schools in less-affected parts of China reopened this week, albeit with measures such as temperature taking and disinfecting.

Over 90% of state-owned enterprises have also resumed operations; small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are also finding their feet again, but at a slower rate. On its part, the Chinese government has worked to ease SMEs' plight by lowering interest rates, deferring social insurance fees, and cutting energy costs.

Above all, those who work close to nature are glad to get back to their jobs. An article in Al Jazeera described the excitement of fisherman Yang Shijiu at getting back on the water. Yang said: "The last two months felt surreal and, trust me, I'm almost 70 years old, and I've seen a lot of things... we're all still alive, and I'm just so happy that the worst has passed."

And on 19 March, new hope was sprung as Chinese authorities said that Wuhan and Hubei province had no new local cases to report, with all 34 new cases recorded over the previous day imported from abroad.

"Today we have seen the dawn after so many days of hard effort," said Jiao Yahui, a senior inspector at the National Health Commission, as quoted in an AP report.

Since then, there has only been a handful of local cases reported in China.

With the improvement in the situation, and the closure of most temporary hospitals in Wuhan and Hubei, medical workers who volunteered to go and help in Wuhan have begun to leave for their own homes.

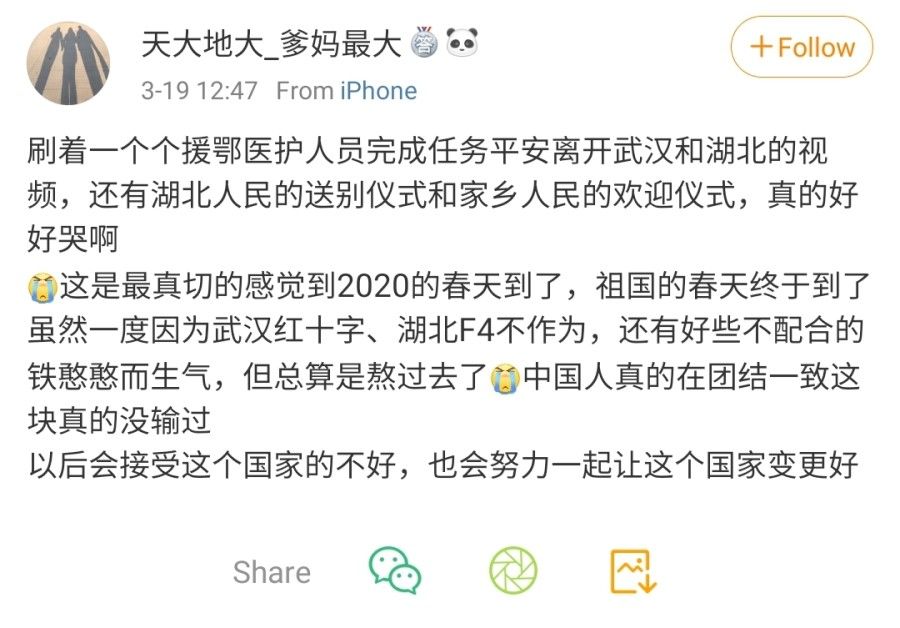

The internet community in China took to social media to show their gratitude, with videos of people saying goodbye to healthcare teams and paying tribute in various ways.

At the end of it all, perhaps this haiku by Edo poet Basho Matsuo (translated by R.H. Blyth) says it best:

さまざまの事おもひ出す櫻かな Samazama no / koto omoidasu / sakura kana How many, many things They call to mind These cherry-blossoms!

This article was put together by Candice Chan, ThinkChina.