US campus protests: What they truly show about US society

As a researcher of China history and an observer of contemporary US society, I intend neither to microscopically analyse student movements without being at the scene nor would I predict the future course of events. Instead, I hope to conduct a more in-depth and critical analysis of US society, politics and campus culture based on the pro-Palestinian student movement taking place on US campuses.

In fact, the mood in the small liberal arts college where I teach has been very calm from the start. There have not been gatherings, protests or support by students or relevant information being published on the college website. The only available information comes from an open seminar jointly organised by a political science professor and a professor of Arabic language and culture from the Middle East. However, such a seminar is equivalent to regarding the student movement and its cause as purely academic.

... student movements are “natural and reasonable” because it is easier for college students, who usually have no vested political and economic interest and self-interest, to demonstrate a simple sense of justice and make demands beyond those interests.

Student movements as purveyors of a ‘simple sense of justice’

The issue at hand involves large-scale student movements and social mobilisation. Typically characterised by a high degree of moral idealism and a simple sense of justice, student movements are “natural and reasonable” because it is easier for college students, who usually have no vested political and economic interest and self-interest, to demonstrate a simple sense of justice and make demands beyond those interests.

They hope that society, and by extension the entire world, will be fairer, and more just and humane, even in the face of violence and threat from the state machinery. This is the fundamental reason for cherishing student movements and for the ease with which they gain widespread public sympathy.

However, as there are specific conditions for student movements to take place, they have not occurred in every college. For example, the current spate of student movements in the US have occurred mainly in large colleges with sizeable student populations.

These college campuses have the advantage of scale, which can more easily foster emotional resonance among participants and facilitate reverberations with the surrounding environment. Small and mid-sized colleges may geographically be further away from academic and cultural centres, have smaller numbers of students, and lack diversity in their student populations. Consequently, it may be harder to organise protests, and the occasional protests tend to be ignored because of their small scale.

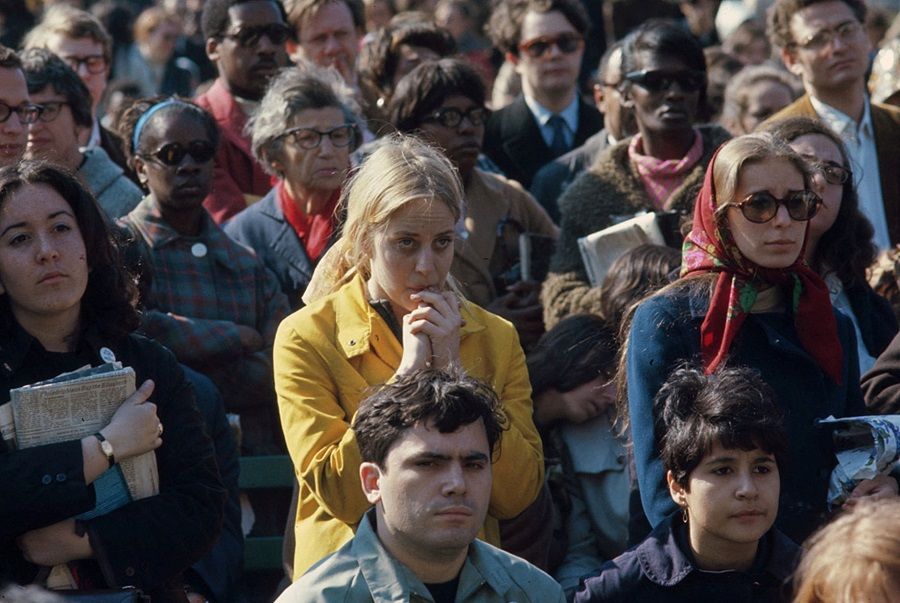

In addition, college tradition is also very important. In the US, Columbia University was the pioneer of protests against the Vietnam War in 1968. This tradition of student activism must surely have inspired and spurred subsequent generations of students. In this sense, student movements are the embodiment of the social responsibility of young intellectual elites.

US college student movements were at the forefront of global youth movements in the 1960s and early 1970s, and had a significant influence on global politics and culture. However, in my opinion, this year’s student movement is unique in that it touches upon the most sensitive and taboo topic in US politics and society, namely, the attitude towards Israel and Zionism.

In fact, the protests in the US against the Vietnam War only involved the US foreign policy at the time and the government’s adamant anti-communist ideology. Some renowned US sinologists have even recalled that they studied China when they were students because the protests against the Vietnam War triggered intense curiosity about “Asian” culture and society. It was the US government’s obdurate anti-communist ideology that inspired their interest in the closed-door China of the Mao era and enthusiasm for research in Chinese socialism.

As the issues involved in the current protests have long been sensitive and taboo topics in the US public sphere and classroom that are not readily broached, the courage of US students to organise large-scale demonstrations in support of Palestine far exceeds that for the movement against the Vietnam War.

Students show courage in addressing taboo topics

The difference between this year’s protests and the demonstrations against the Vietnam War is that Vietnam, once a vassal state of China and a French colony, was an unfamiliar Southeast Asian nation that had little to do with the US, regardless of whether one was sympathetic towards North or South Vietnam.

When I was pursuing my PhD degree, an elderly American classmate told me that many Americans at that time could not even pronounce “Vietnam” and that they would pronounce it as “Nam” with a heavy nasal tone.

As the issues involved in the current protests have long been sensitive and taboo topics in the US public sphere and classroom that are not readily broached, the courage of US students to organise large-scale demonstrations in support of Palestine far exceeds that for the movement against the Vietnam War.

According to figures quoted by China News Service, there have been 34,596 Palestinian deaths and 77,816 injuries caused by Israeli military operations in Gaza from early October 2023 to early May 2024. Humanitarian concerns are the direct trigger for the US college students’ great concern.

Due precisely to the sensitivity of this matter, the US has quickly taken a two-pronged approach to suppress the student movement through college disciplinary action and police enforcement.

In theory, the US constitution guarantees Americans the right to peacefully express their views. However, practical realities reveal a different dynamic. Americans frequently engage in self-censorship to avoid sensitive topics. When exercising constitutional rights involves concrete collective actions, like occupying a building or encampment on campus, clashes with the state machinery become inevitable. In these clashes, individuals are invariably at a disadvantage. This tension underscores the perpetual struggle between the abstract concept of “freedom” and the tangible necessity of “order”, leading to irreconcilable differences and conflicts.

What constitutes “legal” or “illegal” action can only be defined by the police and not the students themselves. No one will fundamentally question democracy and freedom because these are basically abstract and necessary principles. The reality, even in the US, is that these principles must be constrained and even defined by the nation’s might and educational authority, respectively represented by the police and the colleges.

Double standards in choosing when and what to protest

How do the US colleges deal with various external conflicts and their impacts upon the campuses? I wish to illustrate the “art” of so doing in this relatively peaceful and quiet college, where I currently am.

During the wave of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, the then president of this college immediately issued a statement in support of the protests, which gave observers the impression that she showed a sense of justice by siding with African Americans. However, she ignored the fact that the 2021 Atlanta shootings resulted in the deaths of many innocent Asian women. Many Americans ‘interpreted’ the Atlanta shooting incident as an ‘ordinary criminal case’ that is unrelated to racism. This illustrates the considerable flexibility in the definition and interpretation of similar incidents because it is questionable that the incident in which a white man killed several innocent Asian women for no reason was not motivated by race or gender. Are Asian women’s lives, after all, not lives?

Perhaps, the real operating logic of the society is the game of “rights” and “power”, which has little to do with the principles and theories advocating democracy and freedom.

After the Russian-Ukrainian war broke out, this college immediately placed chairs painted in the colours of the Ukrainian flag at several events to demonstrate its moral support. Although the college has appeared to be politically correct and on the moral high ground; this is after all an innocuous move that does not affect actual interests. When the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and the impetus of the student movements at prestigious colleges intensified, this college has once again pretended to be ignorant and uttered nary a word.

As can be seen, in any specific context, the attitude of the powers that be and the latitude afforded to others to express their opinions, including the more thoughtful reflections as well as who can be offended or not, are without a set standard and are all carefully calibrated and controlled.

Those who wield power can judge, choose and interpret, and will adopt double or even multiple standards as well as justify themselves as occasion demands. The rest ultimately can only accept their judgment. Perhaps, the real operating logic of the society is the game of “rights” and “power”, which has little to do with the principles and theories advocating democracy and freedom.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “从学生示威看美国校园文化和社会”.