Prof Eddie Kuo: Singapore's ethnic Chinese have never been a unified collective

In the 200 years of Singapore's history from 1819, the ethnic Chinese in Singapore have lived with diversity, both among themselves and within the larger Singapore community. Eddie Kuo, Emeritus Professor at NTU, traces the evolution of the Chinese Singaporean identity. This is a concept that has seen many iterations, from "guests in a foreign land" to the "overseas Chinese", "ethnic Chinese" and "Chinese Singaporeans".

Ever since its founding, Singapore has always been a migrant society, a diverse society consisting of multiple ethnicities. While ethnic Chinese are one of the constituents of Singapore's multi-ethnic society, this group of people itself is diverse, as are its identities. We may say that the ethnic Chinese are living in an environment of double diversity. Throughout a complex 200-year history, the identity of Singapore's ethnic Chinese has constantly been constructed and changed.

On 29 January 1819, Stamford Raffles, an official of Britain's East India Company, landed in Singapore and signed a treaty with the Temenggong and Sultan Hussein of Johor, thus setting in motion the development of Singapore as a free port. This was the beginning of the island's proper recorded history. Historians do not agree on the size of the resident population at that time. It is said that there were about 150 original dwellers and they fished for a living; but some scholars believe that the actual number was larger, and that these people were scattered deep within the tropical forest. Regardless of how many were residing here at first, 1819 is commonly recognised as the year of the founding of Singapore, and migrants from different parts of the world were drawn to the settlement since then.

Of the population of nearly 560,000 in 1931, 75% were Chinese, about 12% were Malays, and about 9% were South Asians generally categorised as ethnic Indians.

In 1824, Stamford Raffles signed a new agreement with Johor's ruler, allowing Singapore to become a British Straits Settlement. Singapore's population was already over 10,000 at this point. By 1836, the figure had grown to nearly 30,000, the bulk of which comprised people who came from southern China, the Malay peninsula nearby, the Dutch East Indies, India and Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka). Ethnic Chinese constituted the majority (45.6%) of the population. Mostly from Fujian and Guangdong, they spanned across six major dialect groups (Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, Hainanese, Foochow), and had established the diversity of dialect groups as the cornerstone of the ethnic Chinese's social structure and identity just as it still is today.

Demographic statistics tell us more. Of the population of nearly 560,000 in 1931, 75% were Chinese, about 12% were Malays, and about 9% were South Asians generally categorised as ethnic Indians. Slight fluctuations aside, the demographic ratio of these three major racial groups has mostly not changed much over the last hundred years. Indeed, the so-called CMIO multi-racial demographic structure - based on the four racial groups (Chinese (C), Malays (M), Indians (I), Others (O)) as officially defined in Singapore - has been the government's basis of reference since Singapore's independence in 1965 for setting social policies.

Such policies include those pertaining to bilingual education, flat allocation, immigrant quotas, the multi-constituency system, and even the system of presidential election by popular vote. Despite much controversy in recent years, the official position remains unchanged.

Over the last 200 years, the identity of Singapore's ethnic Chinese has gone through four phases.

1. From 'guests in a foreign land' to overseas Chinese: 1819-1912

The first phase began with Raffles' founding of Singapore, and ended with the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912.

The early ethnic Chinese immigrants mainly came from places like Malacca and Penang, in which they had already lived for generations (or more than a hundred years) and developed what is known as Baba (or Straits Chinese) culture. Among them were those who founded business associations in these places, and were local leaders recognised by the local government. These successful businessmen came to Singapore in response to the appeal of the British colonial government. They started businesses here, engaged in crop cultivation, mining, trading and basic construction.

One of the most famous among them was Tan Tock Seng, whose ancestry was traced back to Haicheng (now Longhai), Fujian. He was born in 1798 in Malacca, where his family had settled and made its living as crop cultivators. Tan Tock Seng relocated to Singapore at a young age and became a very rich man with his business acumen. He contributed financially to community-building and various developments. The grandfather of Lim Boon Keng, another leader of the local Chinese, was also a migrant from Haicheng. He first went to Penang, and then relocated a second time to Singapore.

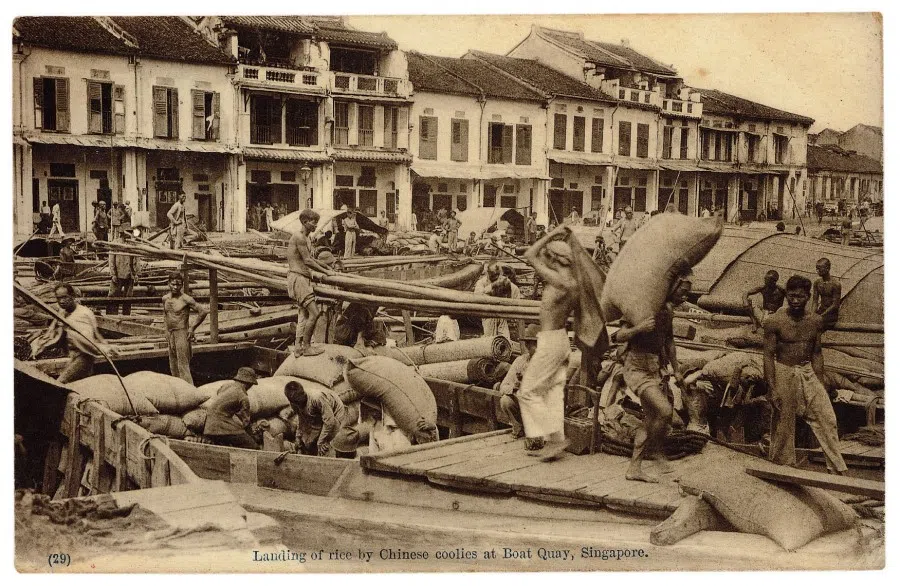

The early leaders of the Chinese migrant community brought in numerous labourers from Fujian and Guangdong to work on local development. Large numbers of coastal dwellers from these two provinces crossed the sea to seek livelihood in Southeast Asia because life was difficult in China due to much social and political unrest in the first half of the 19th century.

An identity tied to dialect groups

During this period, the identity of the Chinese migrants was basically tied to their dialect groups. They thought of themselves as natives of Xiamen or Quanzhou, or Cantonese, Teochew, Hainanese and so on. Although they were all "sojourners from China", the idea of Greater China had yet to emerge, and dialect group identities became the cornerstone of the local Chinese's social structure and identity. The colonial government's tactic of "divide and rule" also helped to reinforce this.

The Great Riots, as it was called, lasted for 14 days, during which violent fighting occurred widely from downtown to the rural areas, leaving over 400 dead and numerous people injured.

Newly arrived migrants from China (the "new migrants") basically had to rely on xiangqin (乡亲 "people from the same native place") - that is to say, the fellowship based on shared geographical and blood ties. Their basic needs of accommodation, employment, education and even various other needs linked to ageing, medical care, funerary arrangements etc. were provided for by their clan associations.

Clan associations associated with different localities in China were loyal to their respective dialect groups. As they each vied for the interests of their own and served their xiangqin, so-called "bang politics" (帮权政治) became prevalent.

Inevitably, there were conflicts of interest between the bang (帮 "gangs", as it were) of the various dialect groups. Fights between the different communities occurred from time to time. A particularly serious one occurred in 1854, when the Hokkiens and the Teochews clashed with each other in a major armed conflict. The Great Riots, as it was called, lasted for 14 days, during which violent fighting occurred widely from downtown to the rural areas, leaving over 400 dead and numerous people injured.

As armed conflicts between different dialect groups became increasingly serious, the colonial government and community leaders were determined to take action to exercise coordination and tackle the problem. Ultimately, it was the Hokkien community, being the strongest in terms of numbers and finances, that stepped out in 1840 to establish the Hokkien Huay Kuan, which helped to harmonise relations between different dialect communities.

By 1906, with the establishment of the General Chinese Trade Affairs Association (the forerunner of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce), the mechanism for uniting different communal organisations for cooperation was complete.

Although based in Singapore, the consulate-general [of the Manchu government] handled matters related to overseas Chinese in various places, including Penang, Malacca, Batavia, Yangon and Bangkok.

'Protecting travelling merchants' and the first consulate in Chinese history

During this period, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, China's maritime ban was easing, and more and more Chinese travelled abroad to different parts of the world. In Southeast Asia, in particular, there were estimated to be as many as tens of thousands of them. For the purpose of "maintaining international relations and protecting travelling merchants", the Qing government decided to establish consulates in places with high concentrations of Chinese residents and protect overseas Chinese.

The first consulate in Chinese history was set up in Singapore in 1877. This was also the year when the British colonial government set up the Chinese Protectorate to deal with the Chinese people's affairs. As the Chinese communities in Southeast Asia grew even bigger, the Manchu government upgraded its consulate in Singapore to a consulate-general in 1881, with Huang Zunxian serving as the first consul-general.

Although based in Singapore, the consulate-general handled matters related to overseas Chinese in various places, including Penang, Malacca, Batavia, Yangon and Bangkok. This was the beginning of the Qing government taking charge of such matters.

A more important development at this time was the Qing government's promulgation of The Great Qing's Regulations Concerning Nationalities in 1909. It differentiated between overseas Chinese who counted as Chinese citizens and those who did not, thereby deepening the concept of huaqiao (华侨 "the overseas Chinese", or "Chinese sojourners").

The Chinese who came south in the early years called themselves guofanke (过番客 "guests in a foreign land") or nanyangke (南洋客 "guests in Nanyang"). Their goal in life was really to return home after making it big, bringing glory to their ancestors and clans. Even if they happened to fall sick and die overseas, they would hope to have their bodies shipped back home. The idea was to return to one's roots, one's place of origin, no matter what, and never be buried in a foreign land.

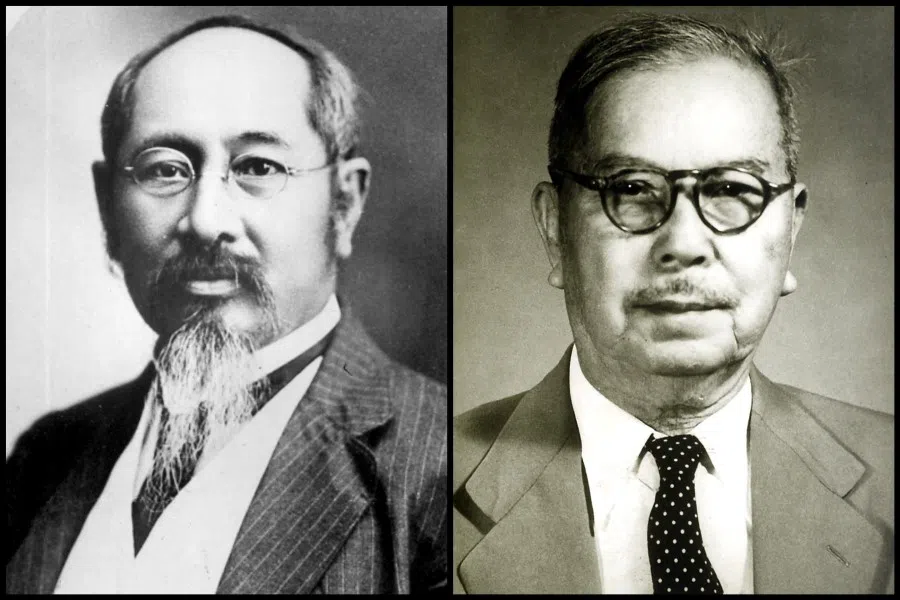

For the former group (the Straits Chinese), Lim Boon Keng was the go-to figure, while his counterpart among the "new migrants" was Tan Kah Kee.

A greater 'China consciousness'

After the First Sino-Japanese War ended in 1895, the Reform Movement began in China. The Chinese diaspora also began to get involved in China's political struggles. The fight between the monarchists and the revolutionaries spread beyond China's borders. With the rise of a nationalist consciousness, the broader notion of the "motherland" began to overtake that of one's "native place". The Chinese identity in Singapore and elsewhere in Southeast Asia pivoted from dialect groups to "China consciousness". The change became more prominent at the turn of the 20th century.

Within the general Chinese society in Singapore, both the "overseas-born" and the "new migrants" had their own well-respected local leaders. For the former group (the Straits Chinese), Lim Boon Keng was the go-to figure, while his counterpart among the "new migrants" was Tan Kah Kee.

The Straits Chinese leader Lim Boon Keng was English-educated. He was the first ethnic Chinese recipient of a Queen's Scholarship, with which he studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh. He became a renowned physician after returning to Singapore. But Lim also had convictions about the essence of Chinese culture, which motivated him to initiate efforts towards social betterment and promote the general enlightenment of the masses.

First, in 1894, he started a movement for the revival of Confucianism in Malaya, championing Confucian ethics. Later in 1899, he promoted teaching in guanhua (官话 the "official lingua franca" - that is, what is known today as Mandarin). The idea was to supersede the existing dialect schools, whose languages of instruction were the Chinese dialects they were associated with respectively. Lim's movement was Singapore's first Speak Mandarin Campaign, so to speak.

As for Tan Kah Kee, we know this from his own memoirs: "In the spring of the year just before the Republican takeover [i.e., 1911], I was 37. I cut off my queue and severed my ties with the Manchu regime."

The two Chinese community leaders worked closely with each other. At some point, Tan Kah Kee went back to his hometown and founded Xiamen University. He eventually invited Lim Boon Keng to serve as its second president, a role in which Lim remained for the next 16 years. This was among the first instances of an overseas Chinese returning to China and founding a school there. In addition, the presidency handover was a fine example of an intersection of the "overseas-born" identity and the "new migrant" identity.

This was the period when the foundations for Singaporean Chinese culture were laid, as epitomised by the founding of many important Chinese schools, newspapers and various Chinese civil organisations.

2. 'Nanyang' and the 'Motherland': 1912-1950

Creating the 'Nanyang cultural sphere'

In 1912, Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary success led to the establishment of the Republic of China, which strengthened the national consciousness of overseas Chinese. An identity based on "ancestry" centred on one's dialect group gave way to an identity defined by the "motherland". From here on, political, economic and cultural exchanges between the "places of sojourn" and the "motherland" became frequent. Thus began an extensive development of Chinese culture in the Nanyang region (Southeast Asia).

This was the period when the foundations for Singaporean Chinese culture were laid, as epitomised by the founding of many important Chinese schools, newspapers and various Chinese civil organisations. The "Nanyang cultural sphere" took shape as the wave spread out from Singapore to other parts of the Nanyang region.

In Singapore, for example, major "Nanyang" institutions and organisations formed during this time included Nanyang Girls' High School (1917), Chinese High School (1919; now Hwa Chong Institution), Nanyang Siang Pau (1923), Sin Chew Jit Poh (1929), the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA; 1938) and the South Seas Society (1940).

Close analysis shows that the important founders and leaders of such institutions and organisations were all from China and they introduced elements of Chinese origin. There were no exceptions. In the first 50 years of the 20th century, numerous educators, newsmen, litterateurs and writers came from China and devoted themselves to the development of Nanyang culture. They laid the foundations of Nanyang culture as well as Singaporean Chinese culture.

...there obviously had to be a closely knit network in those days between various newspaper agencies in the Nanyang region. They must be working closely together and have maintained complex relationships with one another.

Newsmen and historians, among many others

The following are two examples to illustrate this point.

We may first consider the case of Fu Wu Mun, who was born in Quanzhou. He was hired in his early years to join a newspaper in Xiamen, and thereafter went to work for Chinese newspaper agencies in Manila, Yangon and Penang. In 1923, he came to Singapore and served as the Chief Editor of two major newspapers respectively - namely, Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh. (These two newspapers eventually merged in 1983 to form Lianhe Zaobao, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year.)

Fu's wife Liew Yuen Sien was the principal of Nanyang Girls' High School for as long as 40 years, and got to nurture a few generations of female elites. (Fu's granddaughter Grace Fu Hai Yien is currently Singapore's minister for sustainability and the environment.)

Given that Fu Wu Mun had run newspapers in Xiamen, Manila, Yangon and Penang before coming to Singapore, there obviously had to be a closely knit network in those days between various newspaper agencies in the Nanyang region. They must be working closely together and have maintained complex relationships with one another.

Here's another example. Wang Fo-wen, the father of the historian Professor Wang Gungwu, was hired from Shanghai, and came to Singapore in 1927 to teach at Chinese High School. He subsequently went to Malacca and Surabaya to serve as the principal of Chinese schools. After Wang Gungwu was born in Surabaya in 1930, his next destination was Ipoh. In the end, Wang Fo-wen was remembered as an itinerant teacher who served the cause of Chinese education in different parts of Southeast Asia. According to Wang Gungwu's memoirs, his parents had longed to return to their home country all their lives, but ultimately were unable to do so due to the changing circumstances of the times. To them, the unfulfillment was not without regrets.

Contributions to 'the motherland'

Apart from the "motherland's" cultural output to the Nanyang region, of equal importance during this period were contributions to the "motherland" by overseas Chinese. The following are clear testimonies from history, some examples of how the Chinese of Southeast Asia made such contributions selflessly during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

After the Sino-Japanese War broke out on 7 July 1937, Tan Kah Kee was the first to spearhead the formation of an Overseas Chinese Committee for the Grand Assembly for Raising Relief Funds for the Motherland's Wounded Soldiers and Refugees (China Relief Fund Committee or CRFC for short), which called on overseas Chinese to donate money for war-ravaged China. Chinese communities across Southeast Asia followed suit, organising relief fund committees and charity committees of their own for the same purpose.

In the following year, Tan Kah Kee invited CRFCs, charities and chambers of commerce in 45 cities (including Hong Kong and cities in British Malaya, Burma, North Borneo, Dutch Java, Sumatra, South Borneo, Sulawesi, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand) to send their representatives to Singapore to take part in the Grand Assembly of Representatives for Raising the Motherland's Relief Funds from Overseas Chinese of Southeast Asia. On 10 October 1938, 168 overseas Chinese representatives from various places attended the meeting. In the end, they decided to establish the Nanyang Federation of China Relief Funds (NFCRF), with its office in Singapore and with Tan Kah Kee as its chairman.

The manifesto publicised by the Grand Assembly upon the establishment of the NFCRF noted: "China is really fighting to resist foreign invaders and to keep world peace. We call on all of our countrymen who reside overseas to each do all they can and give all they can give. Let us spur ourselves on, encourage ourselves, and make contributions to our country with generosity and great enthusiasm."

Sure enough, the Chinese diaspora across Southeast Asia did respond to the call enthusiastically. Records show that the donations came to as much as 140 million dollars in National Chinese currency in total from 1938 to 1939. Under the NFCRF's leadership, Chinese from all walks of life across the region went on to form the Society for Resisting the Enemy and Saving Our Country. They went on the streets to promote the boycotting of Japanese merchandise, and put up notices everywhere about "ways to sanction unscrupulous businessmen".

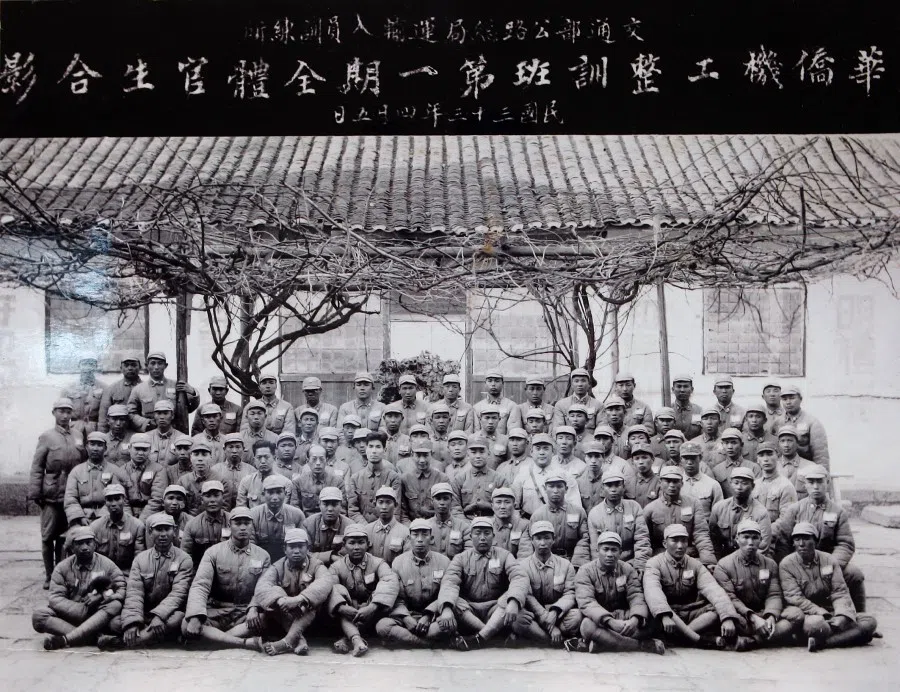

Meanwhile, under the request of China's Republican government, Tan Kah Kee also rallied overseas Chinese to form the Group of Nanyang Chinese Drivers and Mechanics Returning to the Motherland to Serve (the "Nanyang Volunteers" for short). 3,200 individuals took part from 1939 to 1942. Records show that some 1,028 of these volunteers lost their lives to malaria, bombings and the treacherous terrain of the mountains while the Burma Road was being built during the Second Sino-Japanese War. After the war ended, 1,126 drivers and mechanics returned to Southeast Asia, while 1,072 people stayed behind in Yunnan, China.

His grave posts on the left and right bear a couplet written by himself. It says "No need to bury my bones in my old hometown" on one side and "My abode is where I lie with the coffin's lid closed on me".

'Nanyang' consciousness strengthened

With "Nanyang" consciousness in the ascendant, the relationship between the Chinese residents of Southeast Asia and their "motherland" was strengthened, but it also underscored the fact that these Chinese were living far away from their home country in their respective "places of sojourn". They became more deeply aware that these places were their new "homelands".

The most significant development during this period was probably that the board of directors of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce amended certain wordings of their organisation's constitution in 1933. Wuqiao (吾侨 "the overseas Chinese here") was changed to huaren (华人 "ethnic Chinese"), and zhonghua qiaoshang (中华侨商 "overseas Chinese businessmen") was changed to benbu huashang (本埠华商 "Chinese businessmen of this city"). This indicated that identity was beginning to pivot from that of "overseas Chinese" to just "ethnic Chinese".

A change in the same vein could be seen in how people were reorienting their plans for their own lives. In the early days, they hoped to return to their roots (native places), but now the desire was to put down roots in the new "homeland".

An iconic example may be found in the grave of the Chinese community leader Tan Ean Kiam, who passed away in 1943. His grave posts on the left and right bear a couplet written by himself. It says "No need to bury my bones in my old hometown" on one side and "My abode is where I lie with the coffin's lid closed on me". This signifies Tan's farewell to his "old hometown" and his recognition of the new homeland as "my abode".

3. From overseas Chinese to ethnic Chinese: 1950-1965

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the close interactions between China and overseas Chinese were gradually hindered because of dramatic changes in the political situation. The eventual disconnection caused the identity of the ethnic Chinese in Singapore to undergo a fundamental change itself, completing the process of turning from huaqiao (华侨 "overseas Chinese") to just huaren (华人 "ethnic Chinese").

In the Bandung Conference of 1955, China's new government announced that it would not recognise dual nationality. Overseas Chinese had to choose one way or the other: they must either return to China, or bid farewell to the motherland and settle down in their respective places of sojourn as new citizens. At some point, the British colonial government dealt with pro-communist leftists severely under the Emergency Act. Many were taken into custody or sent into exile. A great number of local Chinese thus went back to China voluntarily or were forced to do so. These were the "overseas returnees" of those days.

Meanwhile, in the years after World War II, colonies in various parts of the world were caught up in national self-determination movements, which fought for national independence with the nation-state model in mind. Some of the Chinese in Malaya began to identify with Malaya as their new homeland. They joined the local anti-colonial movement, hoping to establish this homeland on Malaya's own terms. For the ethnic Chinese in Singapore, their home country had changed so much that it was practically drifting far away. So, they chose to truly settle down in the new homeland and put down roots.

For a long time, the identity and differences of the Chinese in Singapore were defined by the opposition between the Chinese-educated and the English-educated, which led to misunderstanding, discrimination and conflicts.

Split among the Chinese-educated and the English-educated

During this time, the greatest divergence in the midst of the ethnic Chinese population had to do with there being two different language streams in education - that is to say, the differentiation between the "English-educated" (those who attended English-medium schools and who were dubbed the "readers of "ang moh books" (ang moh being the hokkien term for 红毛 hongmao lit. red-haired, meaning "white people") and the "Chinese-educated" (those who attended Chinese-medium schools and who were called the "readers of Chinese books").

Due to historical reasons, each of the two language streams had its own textbooks, curriculum and teachers, and their ideas about education differed. The two were each going their way, and seldom had exchanges with each other. With each looking down on the other, there was a lack of understanding between them. (I have described the mentality on both sides as one of "pride and prejudice", as it were.)

This ultimately led to a split in the identity of the ethnic Chinese, a dichotomy of political positions. For a long time, the identity and differences of the Chinese in Singapore were defined by the opposition between the Chinese-educated and the English-educated, which led to misunderstanding, discrimination and conflicts. The crack only began to close gradually five decades after Singapore gained independence.

After years of struggling, twists and turns, Singapore finally became a self-governing state in 1959. It later joined the Federation of Malaysia in 1963, but the differences between Singapore and the rest of the Federation proved to be irreconcilable, even after two years of diligent effort and grappling. Singapore eventually declared its independence on 9 August 1965, thereby completing its full transformation from a colony to a new homeland in the making.

...our Chinese-educated Chinese compatriots would think: 'Our motherland is China'; our Indian compatriots would mentally associate themselves with 'India'; our English-educated compatriots would say, 'Our ancestral home is in Britain', while our Malay compatriots would maintain that this place is theirs. - Ong Chwee Kou

4. The construction of the 'Chinese Singaporean' identity: after 1965

Singapore being separated from Malaysia and forced to become independent was a sudden development. It was nevertheless welcomed by most "new Singaporeans". After 200 years of travail and striving, they finally found an identity "of their own": that of the Singaporean. The following example suffices to show the positive attitude they held.

On 9 August 1966, when the different racial groups in Joo Chiat celebrated National Day for the first time since independence and held a banquet jointly, Ong Chwee Kou the chairman for the event gave a speech, in which he said:

"I feel very excited and proud this evening. I'd like to voice the concerns and fears I used to have. I'm sure everyone used to have this feeling: We don't have a true country of our own. When people asked, 'Where is your country?', our Chinese-educated Chinese compatriots would think: 'Our motherland is China'; our Indian compatriots would mentally associate themselves with 'India'; our English-educated compatriots would say, 'Our ancestral home is in Britain', while our Malay compatriots would maintain that this place is theirs. All such erroneous ideas are now dissipated, never to spin around in our heads ever again. If someone were to ask now where my country is, I would answer without any hesitation: 'My country is the Republic of Singapore.'"

Singapore, the nation-state

After World War II, various colonies across Asia and Africa latched on to national self-determination as the basis for independence and nation-building for emerging countries. Guided by the notion of the nation-state, people stoked the rise of nationalism, and independence was secured after struggling against colonialism. A nation-state usually thrives on its emphasis on one single people, one single culture, one single religion and one single language. Only with this can it forge one single national identity. The Southeast Asian countries that gained their independence after World War II have basically established themselves in this manner.

But Singapore is an exception.

...the Republic of Singapore existed prior to the idea of the "Singaporean" as an identity for all its people and for international recognition. It follows that the identity of the "Chinese Singaporean" did not emerge until there were "Singaporeans" to begin with.

Singapore is a diverse society made up of immigrants and their descendants. It encompasses multiple races, religions, cultures and languages. There is no such thing as a Singaporean race, a Singaporean language or a unified Singaporean culture.

Given such conditions, how are we to construct a national consciousness and identity to be shared by all Singaporeans? How may the Singaporean identity be established? That is the prime challenge for Singapore's nation-building.

As Lee Kuan Yew once put it: "Accidentally I created this entity called Singapore and it resulted in the Singaporean." In other words, the Republic of Singapore existed prior to the idea of the "Singaporean" as an identity for all its people and for international recognition. It follows that the identity of the "Chinese Singaporean" did not emerge until there were "Singaporeans" to begin with.

Building a national consciousness

The challenges faced in Singapore's independence and nation-building are many. Not only must the country seek to survive and preserve itself on the economic, diplomatic and national defence fronts, but it also needs to establish a common national consciousness despite its society being prone to multiple divergences. To achieve that is to build an integrated and unified Singaporean society.

According to the anthropologist Benedict Anderson, nations and states are all built on the basis of an "imagined community". Singapore is no exception to the rule. In fact, we may say that Singapore had to work many times harder than other Southeast Asian countries in this regard.

In the 57 years after gaining its independence, Singapore has insisted on certain important measures for building national consciousness, the most significant one of which was probably the education reform. The four language streams that originally prevailed were integrated into one, such that there remained just one single kind of national-type schools, one school system supported by a unified set of teaching materials and unified teacher training.

Bilingual education also became the rule, with English and one mother tongue set as the concurrent languages of instruction. The most significant impact for the ethnic Chinese was that the long-time chasm between the Chinese-educated and the English-educated got closed. For the younger generations, the "Chinese-educated" and the "English-educated" are just historical terms now.

Language-related planning aside, there are other effective policy measures in place for consolidating the Singaporean national consciousness. These include the National Pledge repeatedly recited in schools and during the National Day celebrations, as well as the National Service that every male citizen of age had to go through.

We may say that Singapore's ethnic Chinese have never been a unified collective. At every phase, despite constant differences, the efforts of our Chinese communities towards fusion and unity had never stopped.

Singapore was founded 200 years ago. That's 200 years of history for Chinese immigrants who came from China. Ethnic Chinese immigrants and their descendants have constituted the bulk of Singapore's population since 1819, making Singapore the only independent, Chinese-dominant country outside of mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Over the last two centuries, the identity of the Chinese here has seen many transformations due to historical reasons. From the guofanke of the 19th century, they became "overseas Chinese", then "ethnic Chinese", and then "Chinese Singaporeans".

The above scheme of characterisations can only be a general narrative, because Singapore's Chinese society has always been diverse. In the 19th century, it was the "overseas-born" (Straits Chinese) versus the "new migrants" (guofanke); in the 20th century, the split was between "Chinese-educated" and " English-educated" and the 21st century is marked by differences between the "original residents" and the "new immigrants".

We may say that Singapore's ethnic Chinese have never been a unified collective. At every phase, despite constant differences, the efforts of our Chinese communities towards fusion and unity had never stopped. Looking back on history, we can see there were continuous efforts over a long time towards gradual blending, treading between the states of separation and union. We may even say there was a prolonged process of "fluidity".

Given the actualities of diversity, the construction of the Singaporean people's identity is bound to be a very long process. After more than half a century of hard work, the new Singaporean identity is gradually maturing, but it is also constantly facing new challenges.

Lee Kuan Yew had raised the question in multiple speeches: can Singapore really fulfil our ideal and become a true nation? As reported by Lianhe Zaobao, he once pointed out during an event in 2011 that "Singapore has been built over time by people who originally shared nothing in common, so what we know today as 'Singaporeans' can only be a concept". He believed that "it would perhaps take another 40 or 50 years before Singapore could become a true nation".

Thus, it seems that the making of both the "Singaporean" identity and the "Chinese Singaporean" identity is an ongoing journey yet to be completed. Continuous effort is still required.

Related: Wang Gungwu: What does it mean to be ethnically Chinese in Singapore? | Does Singapore still want to play an active role in the Chinese-speaking world? | Singaporean Mandarin Database: Recognising the uniqueness of the Singaporean Chinese identity | Trees in a forest: Becoming Chinese Singaporean in multicultural Singapore | What does multiculturalism mean in Singapore? | Challenges of Singapore's Chinese community amid competing influences: Lessons from an old bookstore