Shikumen houses: The first classrooms for the people of Shanghai

The TV series Blossoms Shanghai has revived interest in what life was like in Shanghai during the 1990s, in particular the lanes and shikumen houses unique to Shanghai that became a melting pot of people from different social statuses. Writer Shen Jialu takes us on a journey through old Shanghai.

Television series Blossoms Shanghai surged in popularity at the turn of the year amid the eager anticipation of millions of viewers, sparking fervent discussion. Novels and films are like a joint archaeological excavation using words and images, where fragments of historical culture are unearthed, and each dig of the shovel evokes a cry.

Let us take a look at the shikumen (石库门, lit. "stone warehouse gate", a traditional form of Shanghainese architecture resembling Western townhouses) in Shanghai, a gateway to the psyches and living environments of the characters in the television drama.

In the novel, protagonist A Bao's grandfather is a capitalist who owns a house with a garden on Sinan Road. A Bao's father turns his back on the family to become an underground revolutionary and rents a house near Gaolan Road.

Communal warmth within the lane houses

The film crew recreated the Huanghe Road food street at the Chedun Film and Television Studio (车墩影视基地), and they probably also recreated the shikumen houses. In the novel, protagonist A Bao's grandfather is a capitalist who owns a house with a garden on Sinan Road. A Bao's father turns his back on the family to become an underground revolutionary and rents a house near Gaolan Road.

After 1949, things do not improve: as A Bao's grandfather says, they live a simple life selling household goods, keeping their accounts with a wooden abacus. However, both houses become the backdrop of young A Bao's life.

The parents of A Bao's friend Husheng are Air Force cadres who live on Maoming Road. Husheng's former girlfriend Meirui who appears later on lives in a new-style lane house (里弄房子) by the Suzhou River, with waxed floors, steel windows and intricately carved columns on the staircase landing.

Shanghai residents have always been mindful of the location and type of a person's house - where one lives corresponds with one's social class. No matter one's lot or how messy life gets, one's "first stop" is crucial. Hence, the lane (or longtang, 弄堂) house where A Bao's childhood friend Xiao Mao lives and the concept of "20,000 households" (两万户, workers' housing in Shanghai built in the 1950s) resonates among grassroots readers.

"... the so-called shikumen lanes are a hodgepodge of homes. Anyone can live in any of those residences as long as they can afford the rent. Indeed, all sorts of people live in them; they may not have similar jobs or be of the same status..." - Professor Yi Zhongtian, author of Reading and Cities

In his book Reading and Cities (读城记), Professor Yi Zhongtian comments on Shanghai's lanes: "While Shanghai has the so-called upper corner and lower corner (上只角 and 下只角 respectively; foreign concessions such as Huangpu were traditionally regarded as upper corners, whereas northern areas in industrial Yangpu, home to poor immigrants from nearby provinces, were regarded as lower corners), with the four different classes of residences - houses with gardens, apartments, lane residences and simple shanties - the construction of these homes is generally haphazard... In fact, the so-called shikumen lanes are a hodgepodge of homes. Anyone can live in any of those residences as long as they can afford the rent. Indeed, all sorts of people live in them; they may not have similar jobs or be of the same status."

Yi is not mistaken, but his observations and experiences are far from those of our very own local Uncle (爷叔, A Bao's mentor): the writer of the original novel Blossoms, Jin Yucheng.

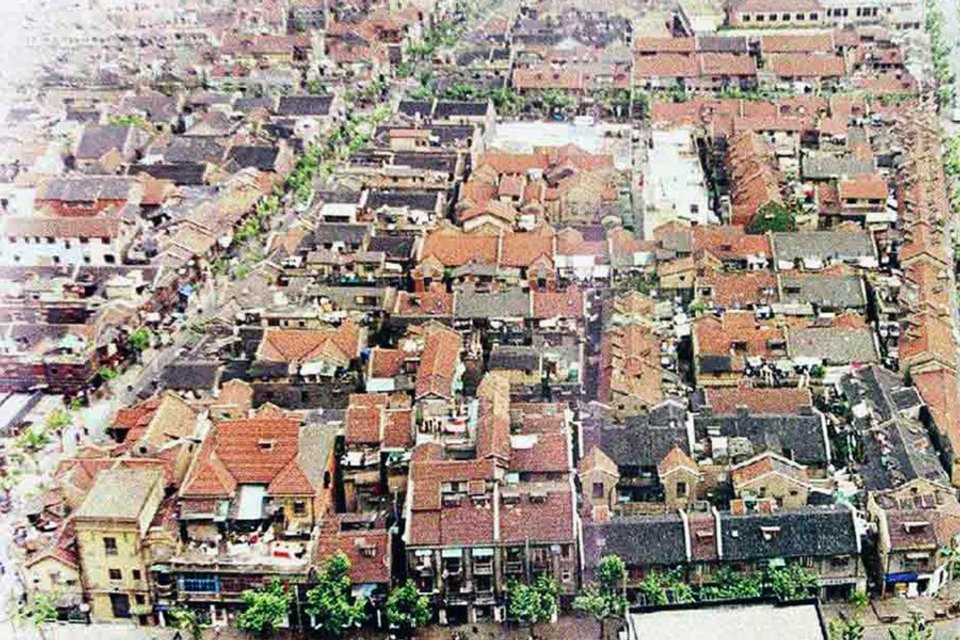

In the 1980s, when housing was at its scarcest, there were over 9,000 lanes in Shanghai's urban area, with more than 200,000 lane houses being home to over 70% of residents. Subsequently, through large-scale urban renewal, living conditions were significantly improved, while entire neighbourhoods of well-preserved shikumen lane houses with historic and cultural value became permanent relics, or brand-new spaces showcasing the city's charm.

Amid urban renewal, Shanghai residents' nostalgia for the social atmosphere of times past, when people saw one another every day and there was communal warmth, is naturally shown in their deep fondness for the shikumen houses.

No two lanes are alike

Shanghai's lanes have always been a melting pot of people, with a pecking order in place. The most prevalent, ordinary and historical are the old-style shikumen lanes. All sorts of people of unknown backgrounds gather together and size one another up as they bustle about amid the mingled cadences of various dialects.

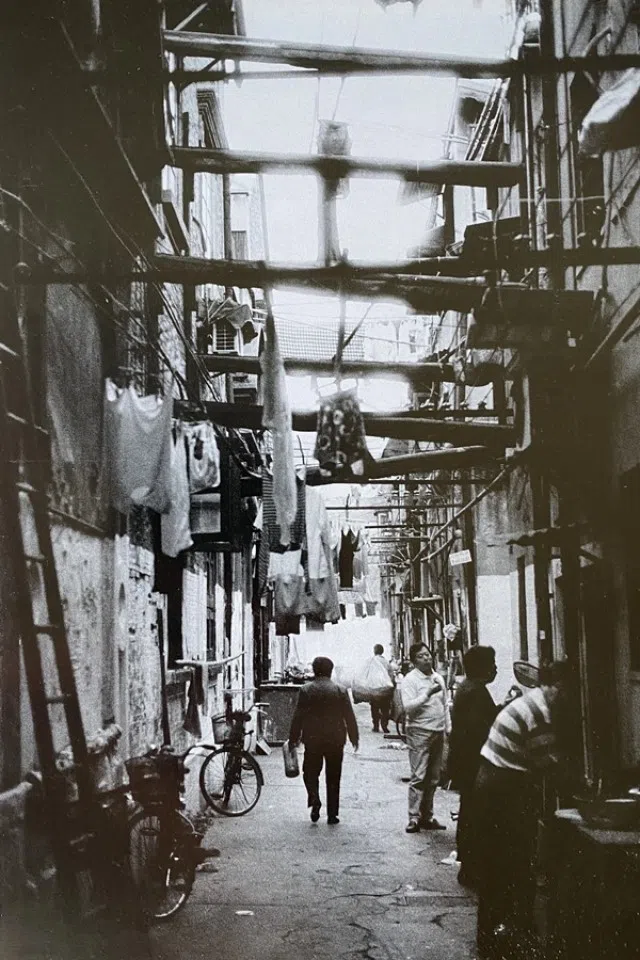

Black-and-white photographs show life in the lanes as vivid and chaotic - communal kitchens and stoves, pancake stalls, cigarette shops, tailors, barbers, production workshops, knitting rooms, injection rooms, neighbourhood committees, private schools, residents' cafeterias - it was a cacophony of life.

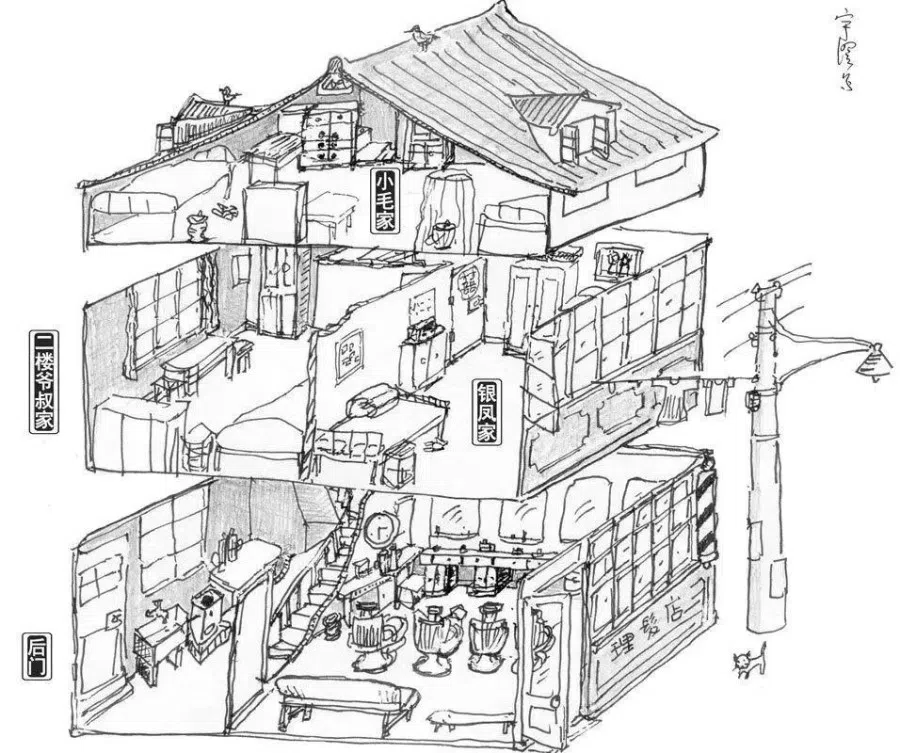

In the novel, Xiao Mao lives in an old-style lane off Changshou Road, near the Kawamura Memorial with its clock tower, known as the "Self-Chiming Clock" (大自鸣钟). In that unique era, "every family eats porridge and a paste of yam and six-grain flour. Xiao Mao's family lives in a third-storey loft (三层阁)... Before the whole family eats, Xiao Mao's mother raises her hand and says, 'Wait, you will eat too much side dishes if the porridge is hot. Let it cool a bit before eating.' Everyone keeps quiet."

On the ground floor is the shop of a barber who speaks the Suzhou dialect. At night after closing, it becomes the common area for the residents of the building.

"In 1990, macerating toilets were introduced, with a device fitted below to break everything up to be flushed into the sewer; these were mainly targeted at people living in such residences." - Jin Yucheng, author of the novel Blossoms

"The smooth-faced woman on the second floor says gently, 'Xiao Mao, you sing so well...'" The woman's name is Yin Feng; she is married to a sailor, Hai De. The couple spends more time apart than together, which means she essentially lives alone in an empty room. Right next door is Uncle.

Xiao Mao, Yin Feng and Xiao Mao's friends the sisters Da Mei Mei (大妹妹, lit. big younger sister) and Lan Lan hide in Xiao Mao's loft to secretly listen to a record of the Shanghai opera Zhi Chao Reads A Letter (志超读信). Everyone is baking in the heat as they do not even dare to open the skylight for fear of alerting the neighbours.

Jin Yucheng's caption on his illustration is very clear: "A typical old Shanghai lane, no courtyard, no flushing toilets. Just posters of [actors] Zhou Xuan and Zhao Dan chatting and laughing, with bird cages hanging around. In 1990, macerating toilets were introduced, with a device fitted below to break everything up to be flushed into the sewer; these were mainly targeted at people living in such residences."

In the mid-1980s, a friend and I went to Changshou Road near the clock tower to see a literary magazine editor who had returned from Hefei to visit relatives in Shanghai, and we found ourselves in a lane house like Xiao Mao's.

Such houses are different from the classic shikumen houses - there are no bedrooms or garrets (亭子间, the space above the kitchen, usually to store sundries or as servants' living quarters), and there is no emphasis on either a front or rear hall. They are mostly local houses constructed by the owners, with its exterior made of single-layer brick walls, windows and doors of different heights, and wooden boards to partition the interior.

Neighbours walking around, coughing, turning on the radio, cursing - every sound is crystal clear. To get some peace and quiet, we each grabbed a cattail leaf fan and a small stool, and our host led us to a spot under a street lamp at Wuning Road Bridge.

Once the Cultural Revolution begins, A Bao's family falls into decline. His grandfather is driven out of the big house on Sinan Road, while his eldest uncle's family moves to the shikumen lanes at Tilanqiao, and his second uncle's family moves to a garret on Qingyun Road in Zhabei.

A Bao is swept up by the winds of the times and moves to the "20,000 households" mass housing in Caoyang New Village.

"Two-storey brick and wood structure, Western-style tiles, wooden windows and doors, cedar floors upstairs, cement floors downstairs, interior walls with a base of mud and straw, covered with a thin layer of plaster... Five households share one kitchen and two toilets."

The dramatic changes in surroundings led to a shift in A Bao's perception and thinking. The novel describes: "Half a drape hangs over the door of their room. A Bao's father has made a bed on the floor; his mother and youngest aunt are already in deep slumber. The family is so close together; it is cramped, it is surreal, but A Bao is grateful to his youngest aunt."

Why is he grateful? Because his youngest aunt is street smart, adaptable and resilient. Coming from the bottom rungs of society, she is accustomed to the ways of the world and is able to remain calm and steady.

Wisdom of lane living: take things as they come

In fact, those who have lived in Shanghai's lanes for a time generally have the wisdom and mindset that, just as ducks eat grain and cattle eat grass, each person has their own fate, and one has to adapt to circumstances.

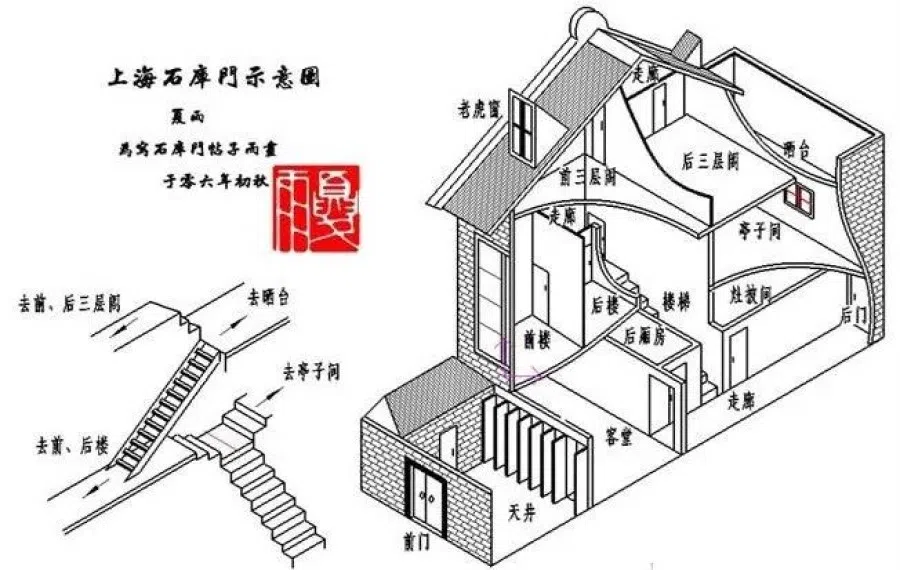

Shanghai's lane houses are mostly old-style shikumen houses, with door frames constructed out of three stone bars - two vertical and one horizontal - or out of ground stones and cement. On the lintels are mountain flowers, with the carvings ranging from simple to intricate, and elegant inscriptions, giving the impression of a literary or aristocratic family.

The houses typically have three rooms upstairs and three downstairs, or sometimes five rooms upstairs and five downstairs. The Yingchuan Jilu building, the only remaining specimen in Hongkou district, can be found in the present-day INLET cultural hub (今潮8弄). They have one master with two smaller bedrooms on each of the two floors. It later became one master and one smaller bedroom due to land constraints.

The courtyard of a shikumen house is a communal space where people move in and out, and is quite important for one's mental state.

Sometimes, tenants have other uses for the space - opening bookstores, restaurants, hospitals, schools and so on. Without changing the overall structure, they knock down the wall between two courtyards, creating a much larger courtyard or garret. Later on, single-room shikumen houses without the smaller bedrooms emerged. Such architecture was found in the buildings where the first and second national congresses of the Chinese Communist Party were held.

The courtyard of a shikumen house is a communal space where people move in and out, and is quite important for one's mental state. In a time of individual households, residents with a taste for refinement might set up a fish tank or grow a few pots of orchids, and make sure their place is well-ventilated, bright, airy and tranquil. However, in a "House of 72 Tenants" (the title of a Hong Kong movie and TV series about crowded communal living), the courtyard is used by ground-floor residents for drying clothes, parking bicycles and setting up coal stoves for cooking.

There is also a passage in the novel where A Bao's friend Tao Tao and Fang Mei (who becomes Tao Tao's wife) go to Chengdu Road to buy records. Mr Meng works in the music store located in a rented house, with a "front hall and courtyard on the ground floor, combined into one large space with stacks of record-filled drawers covering the entire east wall, complete with a movable wooden ladder and records filling every nook and cranny".

After tenants move in and when even the kitchen is occupied, two or three small kitchens often have to be set up in the courtyard so that ground-floor residents can cook.

Behind the courtyard is the guest hall, the most impressive room in the entire house. When all four floor-to-ceiling doors are open, the room is airy and grand. Detailed mosaics cover the floor, with various colours arranged in hexagons, octagons and patterned borders.

If the living conditions are not too cramped and the status quo is not disrupted, the guest hall remains a common area. Put up a classic square wooden dining table against the wall, flanked by a couple of armchairs, and the ground-floor residents can entertain guests, drink tea, play chess, make steamed buns, wrap rice dumplings, and in winter, pickle vegetables and grind glutinous rice flour. Indeed, the voluminous and boxy guest hall is the perfect amplifier.

On one side of the courtyard are the bedrooms, which are further divided into the east and west wings. The front bedroom faces the courtyard, with a row of tall, wide windows offering the best lighting. The windows of the rear bedroom face north, making it an ice box during winter and a furnace during summer.

A "middle bedroom" could also be set up between the front and rear bedrooms if there is an increase in the number of tenants. As there is nowhere to put in windows, a space about two or three feet wide is left above the wall that separates it from the front bedroom, and flat, thin wooden strips are nailed into a rough lattice pattern. It is later sealed with chipboard for soundproofing.

In the novel, Xiao Mao's mother drags him to a shikumen house in Moganshan Road for a blind date. "They enter the kitchen; the door of the guest hall on the ground floor is open, and Chunxiang [Xiao Mao's blind date] stands at the door.

"The trio enter the front room, which is separated into two sections. In the front is a large cooking stove, a square table, a sewing machine, a small side table (面汤台), and a 26-inch Phoenix brand bicycle for women, complete with a full chain guard..."

This was definitely an advantage for discussing marriage in the 1980s, especially given the rear section of the room, with a loft above and a small room below. Hence, Xiao Mao's mother says, "The room is nice, everything is comfortable and neat."

Heartwarming stories contained in eight square metres

The novel says Husheng studied in a private school in a shikumen house, also a precious memory for an entire generation. "The landlady on Ruijin Road let out her living room to be used for classes. Even on cloudy days, she was reluctant to switch on the lights, and the room got extremely dark. Within and outside of the courtyard, people set up charcoal stoves; cattail leaf fans went patter-patter as water dripped on the floor. There were three seats, and umbrellas were allowed, like Zhang Leping's illustrations of Sanmao reading." (NB: Sanmao is the young protagonist in a classic illustrated children's book series.)

The garret is sandwiched between the roof terrace and ground-floor kitchen, which is also a platform for spreading rumours without which worldly affairs lack flavour.

By the third grade, "Husheng went to class at Maoming South Road, in the main hall of a villa with a Western-style chandelier shaped like antlers."

I have always felt that, whether A Bao or Husheng, Jin Yucheng draws on his own life experiences in his writing; the private school is also left with traces of his clear and resonant voice reading aloud.

Out of the garret in the shikumen house comes the charming and flirtatious Mrs Garret (亭子间嫂嫂), and also a long-suffering writer trying to make it in the city. The garret is sandwiched between the roof terrace and ground-floor kitchen, which is also a platform for spreading rumours without which worldly affairs lack flavour.

In the short story Wordless Monologue (无言独白), Wang Anyi writes: "Rumours are another part of Shanghai lanes; they are almost visible, seeping out from rear windows and back doors. What flows out of the front door and front balcony is slightly more real, but still rumours. The rumours in houses with guest halls in the front and bedrooms on the left and right are a bit stale, with the scent of lavender; rumours in the lane houses with garrets and corner stairs are fresh, with the smell of mothballs."

... in order to tell how many households are crammed into the building, just count the number of water taps and light bulbs in the kitchen.

Of course, heartwarming stories constantly unfold within those eight square metres. Mrs Li prepares dumplings stuffed with shepherd's purse (a type of vegetable) and meat, and gives a bowl to each household. Mother Zhang makes leek pancakes and gets everyone to taste them. Old Uncle Zhang lives alone in the rear guest room, blocked off from the sunlight. After breathing in all the fumes blowing from the kitchen, he falls ill and is bedridden for days, and everyone makes red bean porridge and brings it to feed him. And in order to tell how many households are crammed into the building, just count the number of water taps and light bulbs in the kitchen.

Little eateries three feet down

Following China's reform and opening up, Shanghai's lane houses became even more fascinating. The shikumen houses facing the street had a natural advantage, as they were redeveloped into shops, welcoming the first rays of the market economy.

For example, the fictional "Night Tokyo" on the real Jinxian Road, as vividly described by Jin Yucheng: "In the 1980s, the people of Shanghai were smart. They opened small eateries, dug three feet into the ground, which gave an additional level to the shop, extended by an attic. During this period, such two-storey structures were commonly seen on Zhapu Road and Huanghe Road, and it was the same on Jinxian Road. When one entered, it was inconvenient to look up, as though the banisters were legs - or what artist Feng Zikai called 'meaty legs' - dangling high, while discussions upstairs could be heard..."

In the TV drama, business owners like Lingzi, who grew up in the lane, are adept at reading people and are experts at daily chores. They are the goddesses of Shanghai's Bund area.

Shikumen houses were the first classrooms for the people of Shanghai.

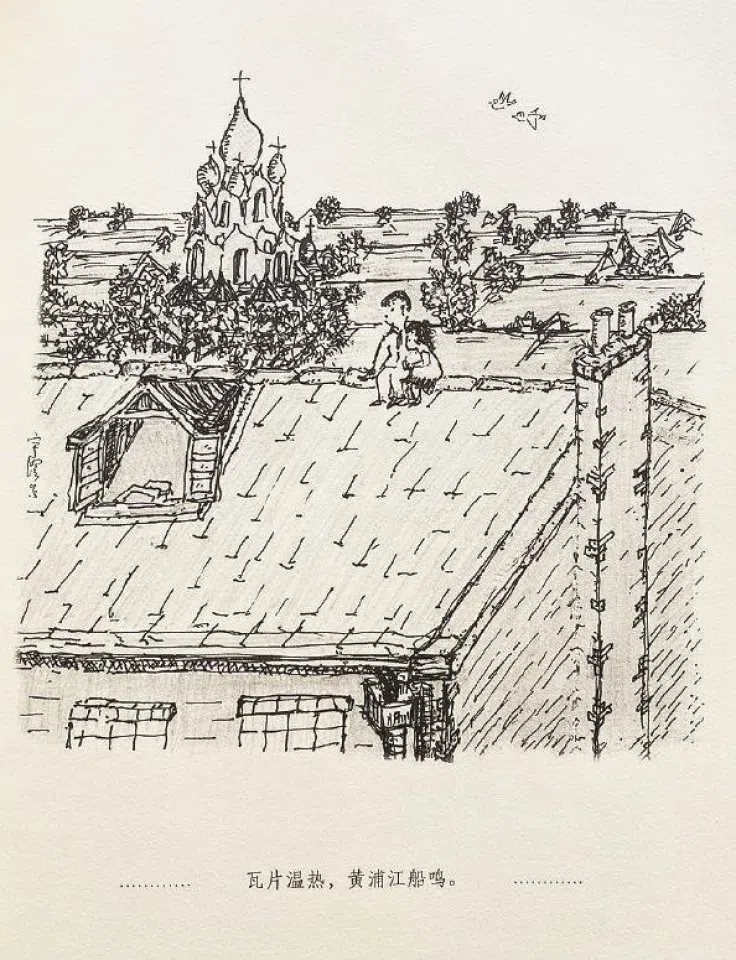

Those who have read the novel must remember this scene: ten-year-old A Bao and the girl next door (later A Bao's one-time girlfriend) six-year-old Beidi climb up on the roof. The daring duo sit side by side, gazing into the distance; the scene is solemn and pure, like a baptism. The roof tiles are warm, and the whistle of a ferry floats across the Huangpu River, melodious as a French horn. Beidi holds on tight to A Bao, and the river breeze ruffles her hair.

Most of today's middle-aged Shanghainese men would have had "escapades" of climbing roofs in their youth; the difference is that they climbed on black tiles, while A Bao and Beidi climbed on square red tiles.

Today, now that the original residents have moved away, the layout and function of the preserved shikumen architecture will inevitably be changed. The original atmosphere cannot be recreated, so amid the popularity of the TV drama, I would suggest rereading the original novel (those aged under 40 should preferably read Shen Hongfei's annotated version). Commit to memory the details of shikumen lanes; it will feel more real. Shikumen houses were the first classrooms for the people of Shanghai.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "跟着《繁花》,看一眼石库门房子".