Sinophobia in Myanmar and the Belt and Road Initiative

Myanmar and China are, in Chinese President Xi Jinping's words, "pauk-phaw", the Myanmese phrase for "siblings from the same mother" that share "fraternal sentiments and close ties dating back to ancient times". Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, on his part, describes the pauk-phaw relationship as "a deep foundation for the comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership" between the two nations.

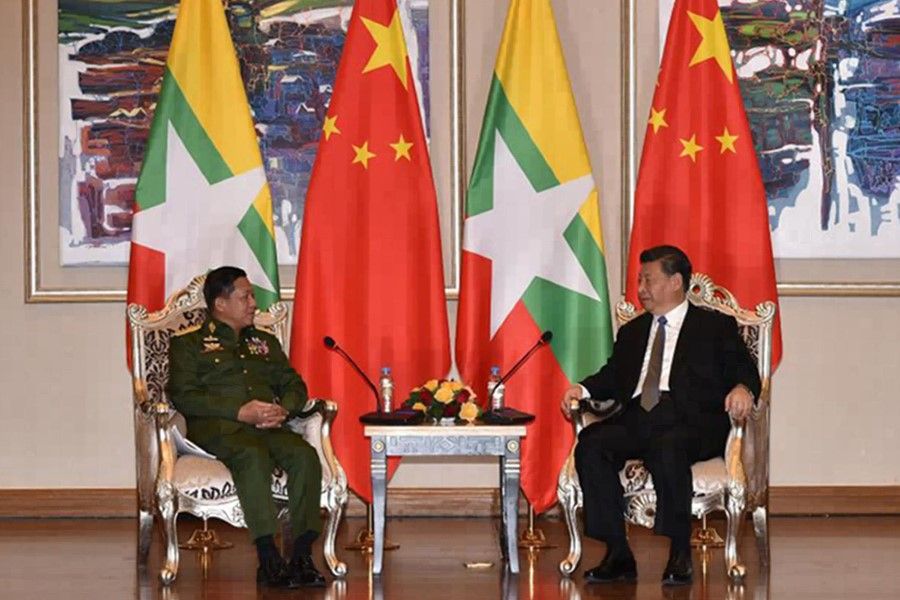

Xi Jinping's visit took place on 17-18 January, six years after he became president. It was the first visit to Myanmar by a Chinese head of state in 19 years. Thirty-three agreements, memoranda of understanding and documents were signed or exchanged between the two countries. China will also provide development aid of 4 billion RMB (around S$800 million) to Myanmar within three years. The two nations have also designated 2020 as the "Myanmar-China Year of Culture and Tourism".

However, most people in Myanmar do not share these positive sentiments.

The signed documents pertain to the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) under China's mammoth Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Saying that the agreements pave the way for the "Gold and Silver Road", Wang Yi borrowed the Myanmar term "shwe lan ngwe lan" (golden road, silver road) and highlighted prospects for the development of cordial relations between the two countries.

Despite ambivalence about China's push to increase infrastructure, investment, connectivity, and trade ties, Myanmar's National League for Democracy (NLD) government welcomed Xi's visit and affirmed its commitment to the deepening of ties. However, most people in Myanmar do not share these positive sentiments. They are aware of the rising influence of China on Myanmar, especially after the surge of international criticism over the Rohingya crisis, the resulting case before the International Court of Justice, and China's support of Myanmar on the international stage.

During his state visit, Xi attended a state banquet hosted by Myanmar President U Win Myint, a luncheon hosted by State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other events at Naypyitaw. He also graced the signing of several agreements. To the Myanmar people, China's strong influence on Myanmar was evident.

Facebook users, private and "independent" media, and commentators/analysts in Myanmar reacted to Xi's visit with hints of sinophobia arising from feelings of fear of Chinese superiority and unease over Myanmar's inferiority.

This bout of renewed sinophobia in Myanmar will be sustained by two main factors. First is continued public fixation with the suspended Myitsone Dam in Kachin State, whose construction China has not yet permanently terminated. Second are concerns raised by surging Chinese tourism and an influx of Chinese migrant workers into Myanmar.

Two dimensions of renewed sinophobia in Myanmar

In recent decades, sinophobia in Myanmar revolved around China's support for Myanmar's military junta during the 1990s and the 2000s, the presence of "illegal" migrants from China in Mandalay, the influx of low-quality Chinese products into the Myanmar market, the rise of a rich class of urban Myanmar-born Chinese, and finally the Myitsone Dam controversy. But in recent years, the BRI, the CMEC, and most recently, Xi's visit, have reignited sinophobia, centred on the suspended Myitsone Dam and on demography.

Continued public fixation with the Myitsone dam project

While discussions and agreements between Myanmar and China during President Xi's visit did not touch on the suspended Myitsone Dam, public fixation with the project continues. Opposition to the dam is almost universal in Myanmar, and it remains the thorniest issue in relations between the two countries. Many in Myanmar believe that the mammoth seven-dam cascade under construction since December 2009 on the Ayeyarwady River - the Ganges of Myanmar - will not only harm the social, economic, ethnic and cultural heritage of the country but also cause an environmental and human catastrophe if the dams fail.

Partly because of popular pressures and partly because of his desire to re-engage with "the West" during Myanmar's transition from military dictatorship (1988-2011) to electoral democracy (2010-), President U Thein Sein suspended construction work on the dam on 30 September 2011.

This bold, unilateral action on Myanmar's part caught China by surprise. It led to China's intensive courtship of Myanmar. Whereas in the past, China had only had to "deal with" generals alone, from 2011 onwards, China has had to satisfy and convince a multitude of actors and groups that include but are not limited to the military, political parties, ethnic armed groups, ethnic Kachin people, environmentalists, and the broader civil society. The current state counsellor and former opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi herself joined the movement against the Myitsone Dam in a letter dated 11 August 2011, somewhat emotionally appealing for saving the Ayeyarwady and reconsidering construction of the dam. Eventually, U Thein Sein suspended the project.

... the only protest to take place in Yangon during President Xi's visit... and the open letter to him from 52 civil society organisations, highlighted concerns over the Myitsone dam.

Beijing and Naypyitaw are acutely aware of the potential backlash from a resumption of the project, but former Chinese ambassador to Myanmar Hong Liang and the State Power Investment Corporation - the Chinese state-owned company building the dam - have often pressured Myanmar and offered assurances of the dam's safety. Although the two sides have not actually said anything substantial or final in public about the possible resumption of the project, the fact that it remains on the table with no official notice of its termination in sight has increased the Myanmar public's fixation with it.

Every time that China is talked about in Myanmar, the subject of the dam clouds the discussion. While other CMEC or BRI projects may, in fact, have greater impact, and while there is considerable debate about them, the Myitsone Dam continues to be the project whose mention instantly captures Myanmar people's attention. It is telling that the only protest to take place in Yangon during President Xi's visit, on 18 January, and the open letter to him from 52 civil society organisations, highlighted concerns over the Myitsone dam. Protests against its resumption have remained frequent even after the popular NLD party came to power in 2016.

Strong public interest in and opposition to the Myitsone dam has also given Beijing and Naypyitaw an opportunity to deepen BRI and CMEC ties through other projects, without the Myanmar public taking much notice.

This means that the Myitsone dam will continue to be the most important flashpoint in China-Myanmar relations. Protests and other forms of activity to oppose it continue to have a high potential to flare up as it was not discussed during President Xi's recent visit to Myanmar; there is also little likelihood that the project will resume until at least after the general elections due in November 2020. That said, the dam undeniably continues to act as the first dimension of sinophobia in contemporary Myanmar.

The demographic dimension of neo-Sinophobia

Sinophobia has also begun to take on another dimension in recent years. This is the demographic dimension, one that Beijing and Naypyitaw may not be able to avoid confronting as easily as they have the dam.

It [sinophobia] has two main sources: the surge in Chinese tourism and the legal or illegal migration of Chinese workers into Myanmar.

Demographic insecurity rooted in immigration has a long history of evoking public concern in Myanmar. This history dates at least to colonial times. Demographic indophobia in colonial Burma in the 1920s-1940s period became demographic islamophobia from the 1990s onwards. It re-emerged with even stronger force after the Rohingya issue became a national issue from 2012 onward. Closed to the outside world for decades, Myanmar remains highly xenophobic, even as millions of Myanmar people live and work in neighbouring countries such as Thailand and Malaysia.

Throughout the early 2010s, Mandalay was the source or point of origin of demographic sinophobia in Myanmar. It is still regarded as the cultural capital of the country. Popular opinion in Myanmar is that Mandalay has seen sizeable Chinese migration, legal or otherwise, in the past few decades and has, as a result, become sinicised. But demographic sinophobia in contemporary Myanmar is not confined to Mandalay alone. It has spread to many places across the country. It has two main sources: the surge in Chinese tourism and the legal or illegal migration of Chinese workers into Myanmar.

Chinese tourism

The contribution of hundreds of thousands of Chinese arrivals to the tourism sector of Myanmar is significant, especially in the wake of the introduction of a visa-on-arrival policy for Chinese passport holders in September 2018. While only 198,256 Chinese tourists visited Myanmar in the first nine months of 2018, 523,449 Chinese did so during the same period in 2019. Its economic contribution notwithstanding, public opinion in Myanmar generally views Chinese tourism negatively.

Chinese tourists often face accusations of showing cultural or religious insensitivity at Buddhist sites. These accusations often go viral on social media.

Myanmar media and analysts often highlight "zero-dollar tourism" when they report and comment on Chinese tourism, as if Myanmar gains nothing from it. Zero-dollar tourism is the practice among Chinese tour operators of selling under-priced tour packages to Chinese tourists but later "encouraging" those tourists to buy overpriced items from shops with which the operators have made special arrangements. Many Myanmar shops and businesses have reported losses due to such practices.

It is impossible that Chinese tourism does not contribute a single dollar to the Myanmar economy because tourists at least pay airport taxes, stay at hotels, pay admission fees, and eat at restaurants. However, Myanmar media, commentators, and Facebook users often fail to understand the economics of Chinese tourism and instead produce alarmist accounts of the phenomenon. Since the surge in Chinese tourism does not seem likely to abate soon, this online phenomenon is expected to continue.

Perhaps in response to the designation of 2020 as the Myanmar-China Year of Culture and Tourism, U Thet Lwin Toe, patron of the Myanmar Tourism Entrepreneurs Association, commented in late January 2020 that "Bamar-town" would soon emerge in Yangon if Chinese tourism goes unchecked. In other words, many of those Chinese tourists will settle down in Yangon and become the demographic majority.

Chinese tourists often face accusations of showing cultural or religious insensitivity at Buddhist sites. These accusations often go viral on social media. One example involves an incident on 8 December 2019 when members of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi's delegation did not remove their footwear before stepping onto the red carpet at the Kuthodaw Pagoda in Mandalay. This was a violation of common rules at Buddhist sites. These pictures went viral, notwithstanding that pagoda trustees later reported that they had immediately asked the men to remove their shoes after seeing such behaviour.

The influx of Chinese workers

The second renewed source of sinophobia in Myanmar focuses on Chinese migrant workers attached to China-owned projects in the country. The number of such workers will rise significantly in the years to come, as CMEC projects go into full swing. Several incidents in recent years have seen Chinese workers and nationals engaged in altercations with Myanmar people or treating them with contempt. Such incidents attract media and public attention.

"It is good that they [Chinese] are coming. They come, invest, and work. But, as [we] have to obey their law when [we] go to their country, they need to follow the law here if [they] come to this country." - Yangon mayor U Maung Maung Soe

Moreover, many Chinese migrant workers coming into Myanmar are believed to be illegal. Popular pressure forced Kayin State Immigration and Human Resources Minister U Min Ko Khaing to vow in September 2019 to stem the alleged Chinese influx into the Shwe Kokko City project being built by Chinese conglomerate Jilin Tatai Group in Myawaddy on the border with Thailand. Myawaddy residents even formed a watch group to check the said Chinese influx.

After an altercation between five Chinese nationals and members of the local administration, police officers, and residents in FMI City (a gated community) in Hlaing Tharyar Township in the outskirts of Yangon on 7 December 2019, Yangon Mayor U Maung Maung Soe said, "It is good that they [Chinese] are coming. They come, invest, and work. But, as [we] have to obey their law when [we] go to their country, they need to follow the law here if [they] come to this country."

Demographic sinophobia often targets language too. Chinese shops in Yangon and Myawady that use signboards written in Chinese alone have been asked to add Myanmar or English text, too.

Even if 10% of them are taken up by Chinese nationals, it means that Yangon will host 200,000 additional Chinese workers.

That said, such episodes remain few. Although their exact numbers are unknown, Chinese workers in Myanmar, illegal or otherwise, may not have reached beyond several tens of thousands. But, in recounting his visit to FMI City in December 2019, a Myanmar journalist wrote, "Once [I] enter FMI City, it is entirely different from Myanmar, and [I] feel as if I have arrived in Shweli [Ruili] in China."

The number of Chinese migrant workers in Myanmar is going to increase dramatically when CMEC projects speed up in the near future, as agreed by China and Myanmar during Xi's visit. For example, the New Yangon City project that the China Communications Construction Company is building on a 20,000-acre site on the west bank of the Yangon River - with the backing of the Yangon regional government - will create two million jobs, according to a claim made by Yangon Region Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein at the launch of the project in March 2018.

Not all of those jobs are or will be meant for Myanmar nationals. Even if 10% of them are taken up by Chinese nationals, it means that Yangon will host 200,000 additional Chinese workers. Given the atmosphere of demographic sinophobia in Myanmar now, such huge Chinese labour migration will lead to communal tensions and pose challenges to the national and regional governments. The media, commentators, and Facebook users will then step up their criticism. The same can be said of existing and future CMEC projects.

Conclusion

Beijing and Naypyitaw are fully aware of the potential backlash from the resumption of the Myitsone dam project. Public fixation on the fate of the dam has given the two governments an opportunity to initiate other Chinese projects in Myanmar. While critics and protestors remain concerned about the dam, planning and implementation of other BRI or CMEC projects have proceeded.

Renewed sinophobia in Myanmar, which stems from public unease over China's continued indecisiveness over the Myitsone Dam project and demographic insecurities provoked by the surge in Chinese tourism and the influx of Chinese workers into Myanmar, now seems inevitable. Expected increases in infrastructure, investment, connectivity, and trade ties between China and Myanmar resulting from the continued implementation of BRI or CMEC projects in the latter country in the months and years to come will only fuel this sentiment. Whether Myanmar and China are prepared to deal with possible communal tensions merits watching.

This article was first published as ISEAS Perspective 2020/9 "Sinophobia in Myanmar and the Belt and Road Initiative" by Nyi Nyi Kyaw.