Why the world needs the BRI

In this first part of a series on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by Professor Gu Qingyang of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP), he lays out the context of the BRI and its role in global development.

Infrastructure may not be the only thing countries need to grow, but it is a necessity . Of the many reasons why countries fall behind in their development, lack of infrastructure comes top. Insufficient infrastructure impedes industrial and urban growth, and prevents countries from accessing the benefits of regional and global trade. This is particularly true for landlocked countries, which face huge logistical costs in development and trade, such that they are limited to trading with their neighbours, which puts them at an economic disadvantage. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) notes that currently, 80% of global trade is done by sea, with an even higher proportion of developing countries being dependent on maritime freight. This means little international trade is carried out by land, and countries with no sea ports are placed at the losing end. The history of globalisation also supports the fact that countries with access to sea freight grow more quickly. So, breaking the infrastructure barrier is key to helping developing countries to progress quickly and get out of poverty, to join the ranks of the globalised economy.

The question is, since insufficient infrastructure has been a perennial problem for developing countries,why can't these nations quickly build their own? Regarded mostly as quasi-public goods, infrastructure lacks exclusivity, hence the private sector either does not build it or builds very little of it, because the returns are just not attractive. However, there are strong positive externalities or third-party benefits in infrastructure, and substantial development cannot take place without ample infrastructure. Due to its unique nature, the government has to take the lead in infrastructure development- try as we might to find innovative ways to bring in the private sector, the role of the government cannot be replaced.

Unfortunately, the governments of most developing countries are facing major problems in gathering resources and getting sufficient funding, which makes it difficult for them to take on the abovementioned responsibilities. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that the governments of most Asia-Pacific countries can only provide about 40% of infrastructure funding needs. The establishment of various multilateral development banks following World War II provided some relief for developing countries, but the total funds and operational efficiency of these development banks are far from sufficient to meet the needs of the developing world.

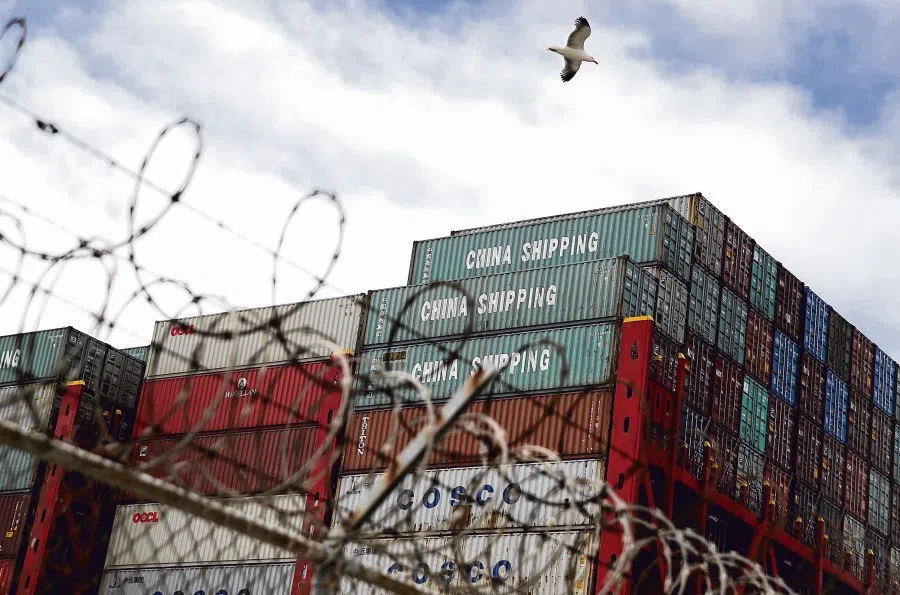

China has been quite successful in infrastructure development. With groundbreaking infrastructure projects such as industrial parks and special economic zones, as well as energy and transport projects, China's economy has grown rapidly. Furthermore, China has built up a large amount of funds, and also expertise in infrastructure construction in various environments. More importantly, China's unique economic system and its government's ability to deploy resources have given it a special edge in infrastructure development, especially in large-scale and cross-border projects. Through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has joined the ranks of global infrastructure construction, which provides a rare opportunity for global development. In this aspect, China's financial model is unique: while infrastructure is being built, it drives the export of facilities and trade. The profits from the latter make up for the low returns of infrastructure construction, so that overall the projects are financially feasible. This model of looking at combined benefits solves the previous problem of low returns on individual infrastructure projects.

China's BRI has also revitalised the globalised economy. Previously, globalisation mainly involved the flow of resources between north and south of the globe. To elaborate: most developed countries are located in the northern hemisphere. With their technology, funds, and management edge, these countries made purchases from the developing countries in the southern hemisphere, who in turn based on their low cost advantage started production and processing, and then sent the consumables back up north. However, the 2008 global financial crisis seriously affected the purchasing power of developed countries, and coupled with the rise of trade protectionism, the north-south cycle was also affected.

Undeniably, as China positions the BRI as a platform for mutually beneficial economic development, China's soft power and influence will increase as the BRI is pushed through. But why should this natural growth in China's influence be criticised, if its initiative can contribute to global development?

The BRI, especially the Silk Road, will improve developing countries' ability to provide energy and logistics, and encourage economic growth and higher income. Trade between developing countries (ie south-south trade) will go up in tandem. This horizontal south-south flow of resources will give new direction to economic globalisation and complement the previous vertical north-south cycle, enrich globalisation, and help to balance global trade. There will be more high-quality goods and technical exports from developed countries, creating a win-win global situation.

Of course, there will be many difficulties in implementing the BRI. Some of these points include: maintaining a feasible international geopolitical balance; boosting communication and strategic coordination between global stakeholders; attracting developed countries, especially the US, to participate in the BRI; bringing in more private enterprises and funding; creating sustainable financial and environmental development; and providing appropriate and sufficient infrastructure according to the diverse needs of developing countries. These are all key as to whether or not the BRI succeeds.

Currently, the discussion on the BRI is mostly focused on international geopolitical competition. Undeniably, as China positions the BRI as a platform for mutually beneficial economic development, China's soft power and influence will increase as the BRI is pushed through. But why should this natural growth in China's influence be criticised, if its initiative can contribute to global development? After World War II, the US contributed to the recovery of West Europe through the Marshall Plan, and it also got something out of it. In the same spirit, we should also acknowledge China's contributions. Taking another perspective: can we find a better solution in place of the BRI? The top global challenge now is growth, and all efforts to contribute to global development should be given priority. The competition between major powers and regions should give way in the face of global development. That should be the main principle in improving the global governance system.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)