Death of China's factional politics

Over the past 30 years, the power structure of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has largely been explicated through the lens of "factions". Its huge explanatory power means that political incidents are very often first examined under the lens of an individual's allegiance to a certain faction, rather than looking at the incident itself. In academia, an important branch of research has developed - elite politics, focusing on the characteristics and power distribution among the various factions.

With efforts by academics such as Victor Shih, an analytical framework has taken shape around China's elite politics, including networks based on coming from the same school, hometown, or workplace, which competes with tournament theory to explain issues such as the promotion of officials and economic growth.

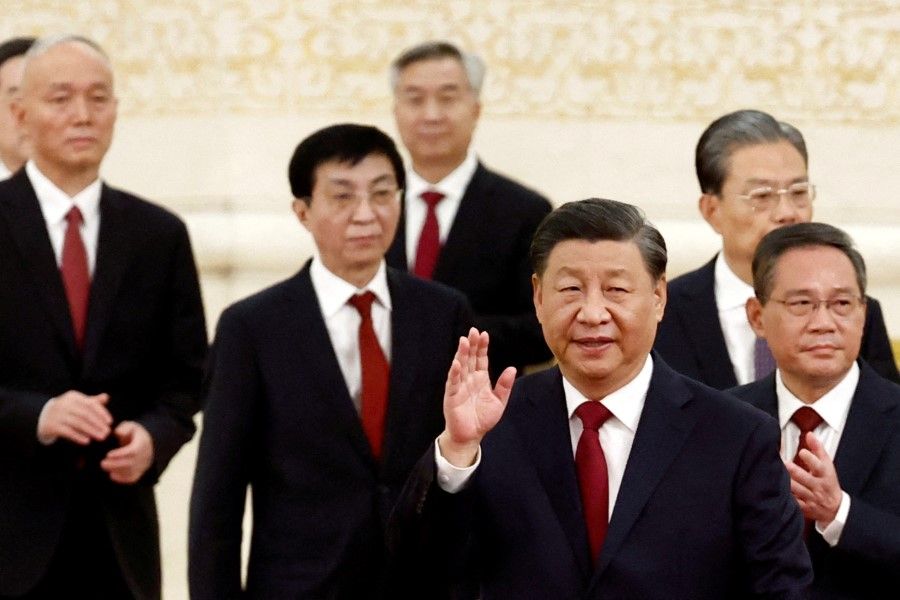

All these norms have been blasted to pieces following the 20th Party Congress. No longer is there the Youth League faction, Shanghai clique or the princelings. The six Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) members other than Xi Jinping are either his loyal followers or theoreticians with vacillating identities. This result has surprised most observers - it seems a party elder also saw the light only at the last moment when it was too late, only to be led away.

'Code of civility' abandoned

Even as 30 years of reform and opening up and power distribution have created a miracle of China's economic growth, it has created complex factional politics. Larger factions are based on organisations like the Communist Youth League, as they are formed through the merging of subfactions. They can also branch out across China with certain common work experiences as the starting point.

In order to survive, some relatively independent small factions choose to navigate between local and central committees, and between various larger factions. For example, PetroChina is tied closely to the powers of Sichuan and Qinghai, while other foundation industries like finance and energy are also overtaken by factions.

In an instant, it became a situation of "nine dragons controlling water" (九龙治水), with power held by a few key persons each taking care of one area. The reduced pull of the central government was clear.

Before Xi Jinping, China's many anti-corruption efforts also went by this "code of civility", where things were not taken too far.

In the 1970s, Andrew Nathan proposed a set of rules for factional politics under an authoritarian framework. Of the many rules, one is the "code of civility", where extreme measures such as assassination, raiding homes or imprisonment are seldom used in tussles between factions, and power deals are brokered through talks between faction leaders. This has been true of China since the era of power distribution, with many political rules that have not been written into the party manifesto, such as the well-known Beidaihe meeting and staying on at 67 and stepping down at 68. The aim is to facilitate compromise between factions and to manage risk.

Before Xi Jinping, China's many anti-corruption efforts also went by this "code of civility", where things were not taken too far. The highest-ranked official who was given the death sentence was vice-chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress Cheng Kejie, who was arrested in 2000. No matter how high the official's rank, their faction would limit the damage and keep going.

The "code of civility" started to be broken in the anti-corruption movement in late 2012. The local and central agency factions around Zhou Yongkang, Ling Jihua and Su Rong were rooted out, showing that the rules of factional politics were breaking down.

The ultimate death knell for factions is the demise of the political life of the faction leader.

Death knell for factions

Xi's far-reaching anti-corruption campaign gravely increased the cost of bribery for promotion, thus making it difficult to establish patron-client relationships and essentially eradicating the microstructure of factions. This practically meant the demolition of large factions formed from the bottom up. While factions formed from spreading their branches will not die off immediately, they have pretty much lost their ability to expand further. Even if they are still capable of occasional counterattacks, they have to accept the fact that they are withering away.

The ultimate death knell for factions is the demise of the political life of the faction leader. After all, a faction can be thought of as a complex binary tree of patron-client relationships based on a strict one-to-one exchange. There would thus be little mutual synergy between faction members from different branches of the tree, which means when a faction leader falls, a strong successor is unlikely to rise and take over. Instead, the members would likely disperse into other factions.

... returning to personality cult and seeking to reinvent political legitimacy will likely be the collective choice.

These basic theories of factional politics are enough to explain recent changes. Commentators must realise that long-term decentralisation has severely weakened the control of the Central Committee. From the perspective of survival, returning to personality cult and seeking to reinvent political legitimacy will likely be the collective choice.

Going by the historical tide of centralisation, any factional rule based on decentralisation will likely no longer work. Thus, this year's Beidaihe meeting hardly created ripples, and the era of "senior politics" since Deng Xiaoping's time has exited the stage of history. The customary retirement age of 68 for the party's top leaders was also ditched, while the once-influential factions were either in a state of disunity or went completely silent.

Even if a new faction is formed, they will be smaller, disappear faster, and have a higher turnover rate than before.

Careening forward amid internal contradictions

While earlier commentator analyses made based on past factional patterns have been proven wrong, pundits have still been quick to latch on to the next hot topic. For example, many people are asking if a new faction will be quickly formed, now that the old ones have fallen. History tells us that new factions will be formed, but not so quickly. Even if a new faction is formed, they will be smaller, disappear faster, and have a higher turnover rate than before.

Moreover, under the new basis of legitimacy, subsequent factions will only be seen as a "subfaction" and not be as powerful as the ones in the period of "nine dragons controlling water". Battles among these "subfactions" would not be regulated from within. Thus, the rules of factional politics as we know it may be broken and the mode of engagement may become even more extreme and unpredictable.

Driving these patterns in history is China's institutional DNA and the eternal and natural contradictory relationship between political centralisation and economic decentralisation.

Since the Qin dynasty, the most successful unified and centralised dynasties have been those that had gone from political centralisation to decentralisation and back again, and from economic disorder to decentralisation and finally centralisation. Driving these patterns in history is China's institutional DNA and the eternal and natural contradictory relationship between political centralisation and economic decentralisation. China is like a train with wheels that keep moving forward at the same tempo on a track that is not controlled by human will.

The rise and fall of factions shows yet again that China's history is repeating itself.

Related: With Xi-ism, is extreme power quietly taking shape in China? | Chinese state media: Party and state leaders step down of their own accord | Xi removes Youth League faction from new leadership | [Party and the man] Ditching presidential term limit an exception not the rule | [Party and the man] Factions and fence-sitters in Xi Jinping's China | Birthplace determining political career in the CCP: Countdown to the 20th Party Congress