The backpacker and travel writer from 400 years ago - China's Xu Xiake

Xu Xiake was an explorer of the late Ming dynasty who traversed across vast mountains and deep valleys in China. He was also the greatest maverick among explorers in Chinese history.

Speaking about world-renowned explorers, most encyclopedias would mention Zhang Qian of the Han dynasty and Zheng He of the Ming dynasty. The former explored the western regions and opened up the old Silk Road; the latter travelled the seas and led the Ming fleet on expeditions to the Indian Ocean, arriving at the East African coast. The travels of Zhang and Zheng are extensively recorded in the annals of history. The two men opened up the channels for east-west transportation and are remembered as "great travellers" and "outstanding explorers". Can Xu match up to them and should he also enjoy these glorious accolades?

Xu travelled to satisfy his own curiosity - he travelled for the sake of travelling and explored for the sake of exploring.

On the surface, Xu's travels can neither be classified as great affairs of state nor great undertakings that changed the course of history. In that sense, it would appear that he is far behind Zhang and Zheng. However, we must not forget that Zhang and Zheng's expeditions were conducted at the request of the imperial court. In their capacity as envoys of the Chinese empire, Zhang and Zheng travelled long distances and sailed the vast oceans to implement major national defence and diplomatic decisions. All these missions were vital to national security and not done voluntarily.

A spiritual pursuit to find one's true self

Xu's travels on the other hand, were entirely up to him and done of his own accord. They had nothing to do with government decisions - it was not that he had received an order from the Emperor to explore uncharted territory or that he was gathering tributes from afar. Xu travelled to satisfy his own curiosity - he travelled for the sake of travelling and explored for the sake of exploring. He travelled so that he could feel strong winds lash his body as they do the land; he travelled so that his feet could kiss every inch of soil and water of the mountains, rivers, and the earth; he travelled so that he could shake off the dust of this secular world atop the high mountains, and wash away the dirt of this mortal life in the vast rivers.

Would this in essence and in modern terms, be the same spiritual pursuit embarked on by scientists seeking facts, artists seeking beauty, philosophers seeking logic, and writers seeking the perfect order of words?

Indeed, his travels were not carried out because of the need to execute a mission or the need to obey the command of the emperor. They were not the result of any external factors, related to the nation's economy or people's livelihood, or done for profit or fame. They were journeys embarked on from one's own beliefs, for the sake of one's passion, and in pursuit of one's simple interests, with unswerving persistence. What kind of mentality was this? What kind of life attitude was this? Would this in essence and in modern terms, be the same spiritual pursuit embarked on by scientists seeking facts, artists seeking beauty, philosophers seeking logic, and writers seeking the perfect order of words?

Xu embarked on his travels seriously and earnestly, taking his own existence as the starting point. He used his own life to study the mountains and rivers and to experience the mystery of the universe for himself. He found joy in adversity, had a clear conscience and did not owe anyone any apology - is that somewhat like the modern person's expression of their individuality? Or is it more in the spirit of Zhuangzi's idea of "wandering beyond (逍遥游)": travel that transcends reality, almost like the legendary zhenren (literally "real person", meaning a spiritual master or the enlightened one) who can go up to the heavens and down to the earth as one pleases? However, we must remember that Xu saw travelling the world as his life's career and he wanted to explore the ends of the earth. His travels were real, just like the footprints he left behind with every step he took. This is entirely different from Zhuangzi's fantasies and imagined travels.

Only filial piety curbed Xu's wanderlust...for a time

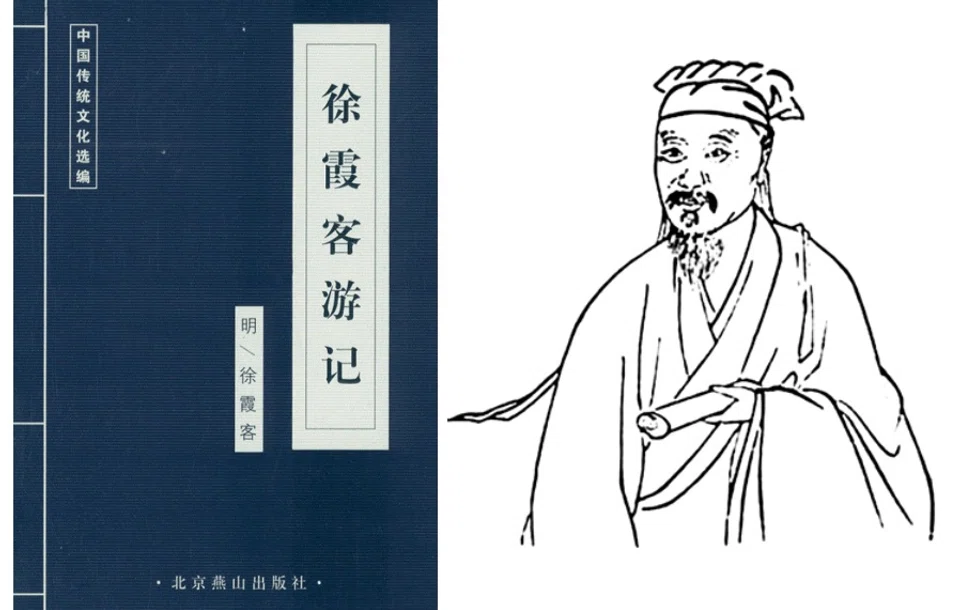

After his death, Xu left behind his famous book, Xu Xiake's Travels (《徐霞客游记》). It contained a record of what he saw, heard, and thought about during his travels and was a personal diary that was not published during his lifetime. It was said that Xu was a filial son and the original intent of his travel diary was to allow his mother to follow his tracks and travel the world through the traveller's eyes, from the comfort of her home. He abided by the ancient teaching that states, "When one's parents are alive, one must not travel to distant places." Thus, when his mother was still alive, he mainly travelled the southeast half of the country and would not leave home for too long a period of time.

The magnum opus of his travels was his ten-thousand mile journey to the southwest.

The magnum opus of his travels was his ten-thousand mile journey to the southwest. He travelled from Zhejiang to Jiangxi via Hunan, Guangxi, then Guizhou, and Yunnan. This journey took him four years and he wrote about ten times more than he did in the past - but this journey took place after his mother's death. Perhaps it had already become a habit for him to record his travels. In the morning, he would be climbing mountains and crossing rivers. At night, he would lay out a piece of paper and record his daily experiences beside a dimly lit oil lamp. His writing was elegant and his descriptions were accurate and precise. It was an outstanding piece of literary work - did he ever think of publishing it and leaving it behind for the future generations?

A backpacker's diary

Xu's travels and travel diary were little known back in the day. Only a few of his relatives and friends knew about his forays and were fond of circulating copies of his travelogues in private. His solo travels around the world were the adventures of a lone ranger, played out far away from human civilisation. His good friend Huang Daozhou (a famous late Ming Grand Secretary and thinker) greatly admired him and once said that he was "a solitary cloud that comes and goes alone (孤云独往还, guyun du wanghuan)". Xu regarded Huang as his bosom friend and they each wrote five poems based on each of the five Chinese characters above.

Ming dynasty painter Wen Zhengming's great-grandson Wen Zhenmeng was a Suzhou scholar and once held the position of grand secretary during Emperor Zhu Youxiao's reign. He was also a good friend of Huang and Xu and had added a postscript to a long poem Huang wrote about Xu. The postscript read, "Xu did nothing else and had no other hobby apart from travelling. He busied himself with moving from one place to another every day and left his footprints on various famous mountains and rivers such as the Five Great Mountains of Mount Heng (衡山), Mount Heng (恒山), Mount Song (嵩山), Mount Hua (华山), and Mount Tai (泰山), as well as Mount Lu (also known as 匡庐 Kuanglu in ancient times), Mount Luofu (罗浮山), Mount Emei (峨眉山), and the Wudang Mountains (also known as 嵾岭 cenling in ancient times). He is indeed the most extraordinary person in ancient and modern times." Clearly, Xu did nothing but travel, living his life traipsing through mountains and rivers all day long. He was indeed an extraordinary figure in history.

In fact, Xu who lived 400 years ago was more like today's backpackers - very cool.