Can China be both economic and security guarantor in Central Asia?

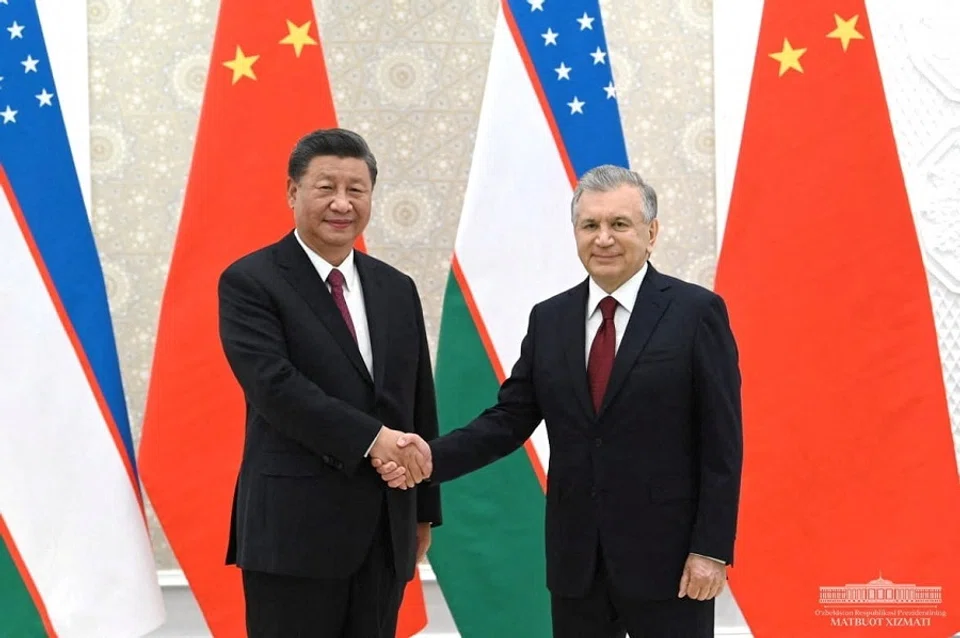

Central Asia is a linchpin between Eurasia and Southeast Asia and a strategic node in China's Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese President Xi Jinping notably visited Central Asia in his first foreign visit in over two years. But while China's economic engagement is welcome in the region, it is currently not a confident security provider. Could things change in the near future?

Before the Covid-19 pandemic wreaked social and economic havoc across the world, Central Asian countries such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan were considered the darlings of the multilateral development banks due to their prospects for strong economic growth. Following the pandemic's detrimental effects on global connectivity, the Russian invasion of Ukraine added a negative ripple effect to the already weak economic growth, setting back Central Asian expectations for a brighter future by a decade.

Nevertheless, Central Asia remains the linchpin between Eurasia and Southeast Asia and a strategic node in Chinese President Xi Jinping's signature foreign policy initiative, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The recent Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in the Uzbek city of Samarkand showcased a shift in the region's balance of power, with China playing a leading role and a much-diminished Russia. Besides the two countries, the organisation includes India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

Beijing is not inspiring the regional actors with enough confidence as a security guarantor.

Economic pivot to the East

Moscow's military presence in the region is not widely perceived as a potential counterweight to Beijing's economic expansion. At the same time, China is a global financial juggernaut, but Beijing is not inspiring the regional actors with enough confidence as a security guarantor.

Central Asia encompasses five countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Each country differs in its social and political context. For example, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan take advantage of the availability of natural resources, and Tajikistan pays the price for the proximity to unstable areas such as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Since the demise of the Soviet Union, however, the five countries share similar challenges to different degrees concerning national identity, proximity to major powers, border and water sharing disputes, youth unemployment, and the difficulties of diversification from the former Soviet-led economic development model.

With the US shifting its focus to the Indo-Pacific and the ongoing war in Ukraine, Central Asia's economic pivot to the East is in high gear.

According to the IMF, in 2018, the overall economic growth in Central Asia was stable at around 4%. However, the war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia have amplified pre-existing problems and cast doubt on possible recovery prospects for Central Asia, as alluded to by the IMF in its 2022 regional economic look report: "Despite better-than-expected upside momentum in 2021, the economic environment in 2022 is defined by extraordinary headwinds and uncertainties, particularly for commodity importers, with higher and more volatile commodity prices, rising inflationary pressures, faster-than-expected monetary policy normalisation in advanced economies, and a lingering pandemic.''

With the US shifting its focus to the Indo-Pacific and the ongoing war in Ukraine, Central Asia's economic pivot to the East is in high gear. Actually, the region's pivot to the East was already set in motion since 2013 with the launch of the BRI during Xi Jinping's official visit to Kazakhstan's Nazarbayev University.

Seeking security guarantees as well

The Central Asia pivot encompasses two dimensions: the first is the natural link between Europe and China along the East-West axis; the second relates to the North-South axis that connects the Middle East and Southeast Asia with China. The latter axis is a crucial connection for Beijing to ensure the flow of goods and people to the ASEAN countries.

China is progressively expanding not only its security role in the SCO but also bilateral security cooperation with the Central Asian states, especially Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

The region's connectivity masterplan includes a renewed railway project linking Kyrgyzstan with Uzbekistan as well as a railway connection to Iran and the Caucasus that will provide access to sea lanes of communication to landlocked Central Asian countries. It was not by chance that before the SCO summit in Uzbekistan, Chinese President Xi Jinping travelled to Kazakhstan on his first international trip since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. The meeting with Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev reiterated the offers of economic and security cooperation and stressed how China supports its neighbour's independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity.

In this respect, China is progressively expanding not only its security role in the SCO but also bilateral security cooperation with the Central Asian states, especially Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Beyond the SCO annual security exercises, Beijing promotes joint border patrols and military training programmes in China linked to transferring military equipment. Also, the role of Chinese private security companies (PSCs) in protecting Chinese personnel and infrastructure is increasingly used as a security gap filler on the international scene.

At the SCO summit, Iran being on track for full membership of the SCO and Saudi Arabia and Turkey looking for a more significant role in the organisation are a case in point. The geostrategic importance of the region and the role that Beijing aims to play in leading the SCO as a counterbalance to Western-led multilateral organisations is part of the ongoing transition of the global security architecture.

The SCO's security focus has not been entirely absorbed by the war in Ukraine as the ongoing crisis in Afghanistan could soon spill over to several of the organisation's members, including China. In this respect, the SCO's pragmatic approach to the Taliban's return to power in Kabul reflects its concerns over Afghanistan's continuing instability and the rise of Islamist terrorism, new waves of refugees, and increased narcotics trafficking.

... while Beijing's foreign policy is supported by the country's economic and financial might, China is still not a confident security provider.

Other than security concerns, Central Asia, as the linchpin for China's geostrategic ambitions, is coming to the fore with Beijing slowly but inexorably connecting the dots between the Middle East and Eurasia. While the US is suspicious of this move as part of the ongoing strategic competition, Russia perceives China's expansion as encroaching on its backyard.

Even before the invasion of Ukraine, the limits of Moscow's economic competition with China were visible. Moscow's tools from Central Asia to the Middle East are increasingly limited to arms sales, the OPEC+ platform that continues to give the Kremlin a space on a crucial forum, and food staple exports. On the other hand, while Beijing's foreign policy is supported by the country's economic and financial might, China is still not a confident security provider.

...the impact of China's expansion in Central Asia will have far-reaching ramifications beyond the Eurasian landmass.

Southeast Asia could play a role

From the Middle East's point of view, interest in Central Asia is tangible following increasing diplomatic and FDI activity. At the same time, ASEAN is more cautious, especially after the recent riots in Kazakhstan and the ongoing skirmishes along the Kyrgyz-Tajik border. Nevertheless, ASEAN could play a role in deepening regional economic cooperation.

In Southeast Asia, the landlocked Central Asian countries are perceived as remote and far away, but in countries like Kazakhstan, the role of ASEAN as a regional stabilisation force and especially the "Singapore development model" is well known and respected among the ruling elite.

While in Washington, there is still a diffused lack of interest in a region that is considered a forgotten heritage of the Soviet collapse, the impact of China's expansion in Central Asia will have far-reaching ramifications beyond the Eurasian landmass.

Related: Xi Jinping embarks on Central Asia visit amid a changed world | Xi-Putin meeting in Uzbekistan: China pulling back from Russia | China gains stronger foothold in Central Asian region | China's BRI carrots for Central Asia come with potential pitfalls | China and Russia compete for influence in Central Asia

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)