China wants a multipolar world order. Can the world agree?

With the rise of China, Russia's reassertion of its power and European integration, the global situation has seen a major shift since the turn of the century. Academics today have different perceptions of the political power configuration of the current international system.

Several Western scholars, such as William C. Wohlforth of Dartmouth College, have termed the 1990s as America's "unipolar moment". Some of them go on to suggest policy ideas for maintaining their country's position as the world's unipole. Their Chinese confreres, however, characterise the post-Cold War international system as a combination of "a single superpower and multiple powerful states".

Yan Xuetong of Tsinghua University's Institute of Modern International Relations, for example, sees the world system as developing towards a new bipolarity presently, whereas Barry Buzan of the London School of Economics thinks that with the rise of China, the global configuration is going from "1+X" to "1+1+X". And, of course, there are many scholars, such as Cui Liru from the Taihe Institute, who continue to believe that the world is obviously multipolar.

China is not a pole at the global level

To the West, the number of poles there are in the world mostly depends on the share of international power resources held by one, two or more countries, as asserted by the likes of William Thompson from Indiana University Bloomington and Jack Levy form Rutgers University. This is a definition in terms of sheer material capability. In this aspect, China is apparently growing closer to the US while widening the gap with other major powers, including traditional heavyweights such as Russia and Japan. Emerging players like India are still far behind China. If we go by a purely strength-based definition, the world is indeed moving towards bipolarity, as some say.

... a country may be inherently powerful, and yet selectively maintain a limited influence over key localities due to the particularities of its own geopolitical environment. Such a power then cannot be considered a pole on the global level.

However, the methodology of counting poles purely on the basis of material capability is seriously flawed as it neglects the importance of geopolitics in international relations. If a particular powerful country qualifies as a pole in a unipolar or bipolar system, it cannot be simply growing muscles in its own corner. It should be exercising significant influence over the system in question.

Within a geographic region, counting poles only in terms of material capability makes sense as no major power, being what it is, can refrain from attempting to influence what happens in its immediate region. For example, according to Robert Jervis of Columbia University, Britain had to take part in the First World War no matter what, because if it did not, it would suffer an appalling negative impact regardless of which side won.

When our scope of consideration is extended to the world system in toto, however, the rule of characterising the international power configuration on the basis of inherent strength alone becomes less applicable. The reason is this: a country may be inherently powerful, and yet selectively maintain a limited influence over key localities due to the particularities of its own geopolitical environment. Such a power then cannot be considered a pole on the global level.

... the world now and in the near future will not be a bipolar world with China and the US as the two poles, since China simply does not and will not have global influence, especially in the field of international security and military affairs.

Heavyweights that hold truly global influence are actually hard to come by. Historically, China, Japan and Germany only wielded regional influence, but each of them still counted as a pole in the wider arena during particular periods. The following must thus be recognised: apart from possessing tremendous national strength, a country that is a pole in a unipolar or bipolar system should be one wielding decisive influence over at least one of the key strategic regions of the world (Europe, East Asia, North America or the Middle East).

By this standard, the world now and in the near future will not be a bipolar world with China and the US as the two poles, since China simply does not and will not have global influence, especially in the field of international security and military affairs.

A multipolar world

The world is actually multipolar in the overwhelming majority of circumstances in history. Although there have been many cases of regional unipolarity, it is very hard to say whether a unipolar global order has ever been in place.

The US was regarded as the sole superpower during the early years of the post-Cold War era by many theorists, yet it is not unquestionable whether its national strength had truly reached the unipolar level in the strict sense. After all, one would expect a unipole within any multinational system to be stronger than all the other countries combined, or at least the sum total of the major powers therein.

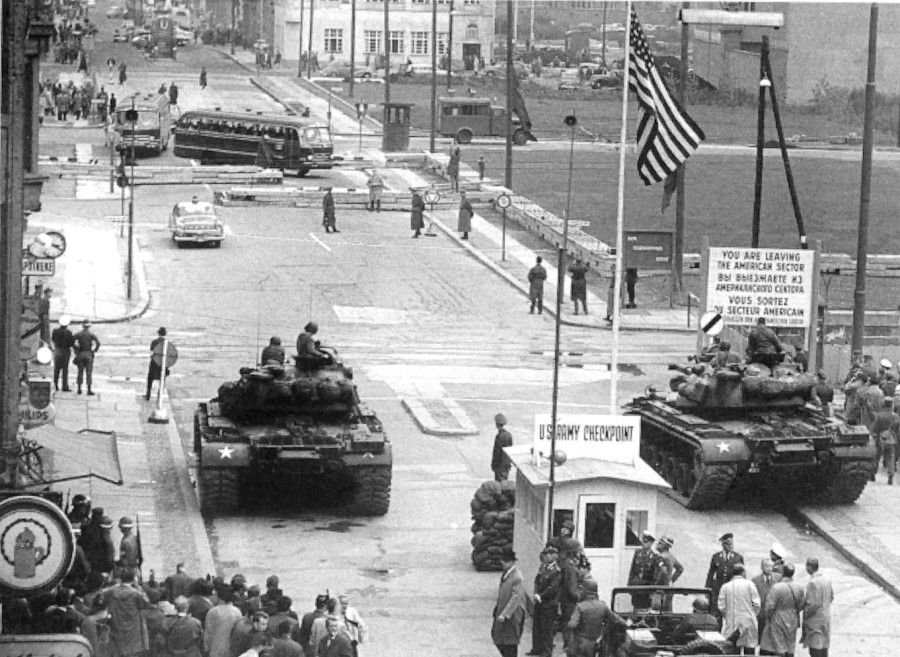

The bipolar global order during the Cold War period was something extremely rare. It came about fundamentally because of the consequences of World War II and the then USSR's geographical location.

During World War II, all the major powers apart from the US and the Soviet Union had taken a debilitating blow, and the militaries of these two countries had marched into key strategic regions around the world. Following that, America was extensively involved on the fronts of Europe, West Asia, North Africa and the Pacific region. Out of these forays grew its system of global alliances.

On the other hand, the Soviet Union, being territorially contiguous with Europe, the Middle East and East Asia, strove to establish buffer zones and pro-Soviet regimes in these three regions. These developments eventually led to the total US-Soviet face-off in key parts of the world.

... the world today is really on an obvious trend towards multipolarity.

Although China is continually on the rise currently in terms of material strength, its geopolitical environment is very different from that of the former USSR. China is in the eastern part of Asia, not directly contiguous with other key regions of the world like the Americas, Europe and the Middle East - that is, if we disregard the link to Afghanistan via the Wakhan Corridor, which is not yet a highly engaged connection at all. Although China has significant interests in these regions, they (especially Europe and the Americas) are not of life-and-death criticality, nor do these localities receive substantial decisive influence from China.

In contrast, because of geographical proximity, Russia has quite a hand in the affairs of Europe and the Middle East. The EU too, has been a decisive force not only in Europe (given that the US supports the management of European affairs by Europe itself), but also in North Africa.

Japan's influence over East Asia cannot be underestimated too. In view of such complexity, if both national strength and geopolitics are taken into account, the world today is really on an obvious trend towards multipolarity. China, the US, Russia, the EU and Japan are all strongly influential in the world system, not to mention the possibility that India and Brazil might also play pivotal roles in the future global dynamics.

Even though some might say that the US-dominated international order is both unfair and unjust, it plays a crucial role in maintaining the fundamentals of the international order.

Looking ahead: China vis-a-vis other players

The US

The US will continue to make its presence felt to a decisive degree in the international arena. America's intention to maintain its unipolar hegemony, its diplomatic tradition of seeking out monsters to be destroyed, and its messianic zeal for exporting its ideology all pose a serious threat to the global order and to China's security.

Even though some might say that the US-dominated international order is both unfair and unjust, it plays a crucial role in maintaining the fundamentals of the international order. If America were to suddenly implement a policy of total withdrawal, the whole order is bound to fall into acute unrest. Even in the Asia-Pacific region, where China's long-term goal is to neutralise American influence, any sudden withdrawal on America's part before China and Japan could come to a total, conciliatory understanding with each other would cause Japan to accelerate its rearmament and thereby spark regional tensions. The regional order would be grievously impacted, resulting in exacerbated uncertainty.

China must not only prepare itself for a long-term struggle in East Asia against the US, but also master the fine art of wrestling without breaking relations between them.

In an ideal situation, when a stable, predominant power rises within an important region of the world, a strategic contraction and retreat from the general locality on America's part is good for the stability of the said region, provided that it is done in an orderly, progressive manner. China should not see the abrupt withdrawal of American influence from any key region of the world (or the catastrophic collapse of such influence therein) as beneficial. In reality, China must not only prepare itself for a long-term struggle in East Asia against the US, but also master the fine art of wrestling without breaking relations between them.

The EU

Between China and the EU's member states, there is no state of geopolitical confrontation and conflict. Just as the European countries have no vital interests in East Asia, China has no such interests in Europe too. China should respect the EU's contributions to global governance (and, of course, decisive role in European affairs), as well as the substantial clout held by France over the circum-Mediterranean region.

Russia will continue to be China's long-term partner in its conflicts with America.

At the same time, China could also seek to secure the EU's future acknowledgement of its status as a key player in East Asia formally or tacitly. There is more on the to-do list, especially in encouraging the EU to adopt policies independent of the US in international affairs where East Asia is concerned, for instance, in lifting the arms embargo on China.

While the pandemic will have serious short term repercussions on China-EU relations, it should not affect its fundamental framework.

Russia

Russia will continue to be China's long-term partner in its conflicts with America. The points of concern for the Chinese and the Russians actually differ because of geopolitical reasons. Russia's economic and political centre is geographically close to Europe and the Middle East, whereas for China, East Asia is where the action is. However, since vital interests for China and Russia do not overlap much, these two countries are not in serious conflict with each other. Furthermore, they both face pressure from the US in the regions where their vital interests lie, which only drives the two to huddle closer together.

Nevertheless, differences in the two countries' geopolitical interests mean there will always be limitations to their bilateral cooperation. When China comes into serious conflict in East Asia with America's interests and allies, Russia may not necessarily provide important aid. Similarly, when Russia clashes hard with the US or the EU over its interests in Eastern Europe or the Middle East, China may not necessarily stand up for Russia resolutely.

In addition, the two countries are not entirely on the same page in their attitudes towards the Korean peninsula issue. Nevertheless, limited expectations for working together on the ultimate level should not get in the way of stable, long-term cooperation between China and Russia. In the foreseeable future, both sides will still support each other in their rivalry and conflict with the US. Through exchanges and cooperation in the economic and military domains, the two will help each other and develop together. It is a beneficial win-win for both.

Japan

Japan is still a major player in global economic governance and the affairs of East Asia. China handling its relations with Japan well is pivotal to the successful establishment of a China-centred East Asian strategic security order.

Barring major abrupt changes in China's domestic order, China should pull further and further ahead of its eastern neighbour. This growing power disparity, coupled with the bilateral issues of divergent perspectives on history, territorial disputes, as well as moves for Chinese control over the South China Sea (which translates into a stranglehold on Japan's access to vital resources), will stir up intense unease in Japan.

How is Japan to be moved away from its reliance on extra-regional backing and increasing its military strength, and yet maintain its sense of security and confidence within the envisioned China-centred East Asian system? This issue is closely tied to a necessary easing of the Japan-US alliance, and is what China must work out in its foreign relations.

China's basic policy in the multipolar world should be pro-Russia, maintaining peace with Europe while pacifying Japan.

India and Brazil

For the emerging power of India, a strategy of hedging should be adopted. There should be mutual respect for each other's sphere of influence, if India is willing to distance itself from America's China policy, give room to China's influence in East Asia formally or tacitly, and keep the sphere of its own influence to the west of Myanmar and south of the Himalayas.

As for the other emerging power of Brazil, a strong political, economic and military player in the Western Hemisphere will be beneficial to China, as it will help divert some of America's attention.

Generally speaking, China's basic policy in the multipolar world should be pro-Russia, maintaining peace with Europe while pacifying Japan. This is grounded on the recognition that the multiple poles are each to wield dominance within their respective geopolitical purviews. At the same time, while keeping stable relations with the United States and managing differences, China should make efforts so that the American presence in East Asia is to be gradually neutralised and balanced, and to slowly win support for the establishment of a China-centred strategic security order for this part of the world.

China should not neglect the secondary and minor powers, especially smaller powers around China with no alliance relations with the US. Since in a multipolar world, they might be drawn into the circles of other poles if China adopts too assertive policies upon them

China could seek to work with the other powers for a considerably long time into the future towards nudging the US - that is, urging it - to withdraw from East Asia in an orderly, progressive fashion, and help in creating a new world order in which major powers assume more responsibility in their own regions. Such a world might bear some resemblance to the policemen blueprint after WWII, but newly envisioned as comprising the US, Europe, China and Russia.

With regard to the fragmented geopolitical swathe that is the Middle East and, in terms of geopolitical structure, the currently forming region of sub-Saharan Africa, China could act as benefits dictate, while keeping close coordination and cooperation with other interested parties. China could keep to a limited strategic security involvement therein and not let itself be deeply mired in these affairs. It could support the UN to accomplish its mission in these places.

Related: Wang Gungwu: Even if the West has lost its way, China may not be heir apparent | A great America is in China's interest | 180 years later, China is still an outsider to the Western-led world order | In a world split apart, where do you belong? | Covid-19: A leaderless age is fast approaching