China's growing influence in the Indian Ocean: Wang Yi's visit to Comoros, Sri Lanka and the Maldives

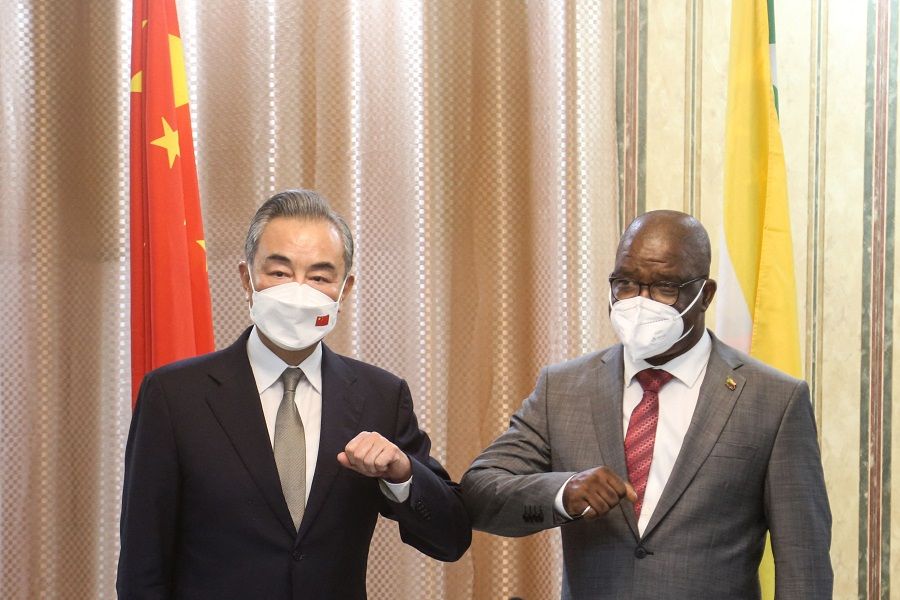

Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited three strategic island states - the Comoros, Maldives, and Sri Lanka - as part of his annual African tour at the beginning of January. Offering wide-ranging cooperation - from vaccines to infrastructure development - he expanded China's regional reach, made new friends and launched a fresh bid to overcome some of the recent setbacks for Beijing in the Indian Ocean littoral.

Notwithstanding the physical distance from the Indian Ocean, the special relations Beijing cultivates in the region will slowly but surely make China a force to reckon with in the littoral. While China's interest in the Indian Ocean has grown steadily since the turn of the millennium, the island states of the ocean have gotten a high priority.

As China emerged as a great trading nation in the 21st century and its interdependence with the markets and resources of the Indian Ocean rose rapidly, Beijing ramped up its political, economic and security engagement with the littoral. Since 2008, China has regularly deployed a contingent of naval warships in the Gulf of Aden and established its first foreign military base - a logistical supply facility - in Djibouti during 2017.

Strategic importance of island territories in the Indian Ocean

There is speculation that China, which Beijing denies, is looking for additional military facilities in the region. Meanwhile, the Indian Ocean littoral has become an important part of China's expansive Belt and Road Initiative and generated an impressive commercial profile for Beijing in the region.

Throughout modern history, islands have been of special interest to maritime powers. As critical way stations in long-distance oceanic travel, as potential bases to dominate the sea lines of communication, as outposts to facilitate traditional and space communications, and as locations for naval power projection, island territories have been valued by great powers.

Like the Portuguese, the Dutch, the British, the French and the Americans, China too, is eager to acquire access to and influence over some of the small island states in the Indian Ocean. Although not widely noticed, this focus has been evident for a while.

Beijing's consistent high-level attention has produced good returns for China in terms of a significantly expanded economic, political and strategic presence in the Indian Ocean island states.

In 2007 at the end of his African tour, the Chinese President Hu Jintao surprised the region by visiting Seychelles in the Western Indian Ocean. Putting a tiny island republic of less than 100,000 people on Hu's itinerary was neither whimsical nor accidental. It signalled the new importance of the Indian Ocean island states in rising China's grand strategy.

In 2009, Hu Jintao travelled again to Africa and concluded his journey in Mauritius - the hub of the Western Indian Ocean and Africa. In 2014, President Xi Jinping travelled to the Maldives and Sri Lanka. It is probably a matter of time before Xi travels to the Comoros and Madagascar in the Western Indian Ocean. Beijing's consistent high-level attention has produced good returns for China in terms of a significantly expanded economic, political and strategic presence in the Indian Ocean island states.

For three decades, the first diplomatic task of the Chinese foreign minister in the new year has been to visit Africa. This year, Wang's trip had a distinct Indian Ocean flavour to it. His first two stops were in two important Indian Ocean states - Eritrea in the volatile horn of Africa/Red Sea and Kenya on the African east coast.

In Eritrea, Wang announced the launch of a new strategic partnership between the two nations, and in Kenya, he reinforced expanding economic cooperation with a number of new agreements, including one on digital economy. In Nairobi, Wang also announced Beijing's decision to set up a special envoy to coordinate Chinese engagement with the Horn of Africa that connects Africa with Asia and the Indian Ocean with the Mediterranean.

Pushing India out?

In the islands, China outlined an ambitious agenda for the Comoros, pushed back against the growing Indian influence in the Maldives, and reinforced China's growing salience in the Sri Lankan economy.

In the Comoros, Wang promised to become a reliable long-term partner and achieve three of its immediate goals - universal immunisation, eliminating Malaria, and supporting the island's developmental strategy called "Emerging Comoros Plan 2030". This ambitious plan wants to raise the island's per capita income from US$1400 to US$4000 through rapid transformation of the island's economy. Wang declared that China is ready to step in.

In the Maldives, domestic politics has become volatile and has enveloped its foreign policy. The current government, led by Ibrahim Solih, pursued an "India First policy", but China is not ready to take no for an answer. During his visit, Wang Yi sought to build on the significant economic cooperation initiated under the previous government headed by Abdulla Yameen, who turned away from India towards China.

Wang's overtures to the Maldives come amidst a movement led by opposition forces demanding to push "India Out" of the nation. The campaign alleges that India's growing economic and security cooperation undermines the sovereignty of the Maldives. While the government has rejected these charges, there is no denying the pressure on it to pursue a more balanced policy between Delhi and Beijing.

India and China are also deeply involved in the domestic politics of Sri Lanka. Delhi got sucked into the civil war between the Sinhala majority and the Tamil minority in the late 1980s and continues to press the case for political devolution to Tamils in the north and east of the country. China, on the other hand, had extended unequivocal support for Colombo and emphasised its non-interference in the domestic politics of Sri Lanka.

This has dramatically transformed China's ties to Sri Lanka, once the civil war came to an end in 2009. Although Beijing's rising economic involvement in the Sri Lankan economy has been widely criticised - at home and abroad - as "debt diplomacy", Colombo's dependence on China has continued to rise.

While there is some domestic resentment against Chinese presence in Sri Lanka, Colombo's options have been limited. It had to settle a dispute with China, in Beijing's favour, on the payment for the import of fertiliser that was alleged to be contaminated by protesting farmers.

With the Sri Lankan economy in shambles in the wake of the pandemic, Beijing has stepped in to stabilise Colombo's dire finances with a US$1.5 billion currency swap facility. To be sure, India has gained some ground recently by winning some major infrastructure projects - the construction of Colombo Port's west terminal and the modernisation of Trincomalee oil tank farm.

But it has not been at the expense of China. During the visit, Wang announced no new Chinese initiatives either on debt restructuring sought by Colombo or new projects. He participated in opening the Marina promenade of the Colombo Port City - a prestigious project developed by China. Sri Lanka hopes investment flows into the Colombo Port City from China and other nations will make it a viable project and shore up Colombo's finances.

At a time when the US and the Quad are struggling to lend some economic salience to their much debated Indo-Pacific strategy, Wang's Indian Ocean sojourn was first and foremost about expanding the economic engagement with the littoral.

Gaining an advantage in tussle with India and the US

Wang Yi's trip to the Indian Ocean islands highlights Beijing's significant advantages in the growing contestation with the US and India in the Indian Ocean. At a time when the US and the Quad are struggling to lend some economic salience to their much debated Indo-Pacific strategy, Wang's Indian Ocean sojourn was first and foremost about expanding the economic engagement with the littoral. This gives a solid foundation for long-term Chinese geopolitical ambitions in the region.

While the US finds it hard to square the ideology of human rights and democracy promotion with the strategic imperative of building partnerships without a reference to the internal political orientation of potential allies, China's emphasis on non-intervention in internal affairs has helped Beijing gain new ground with the local elites.

In emphasising sovereign equality, China also finds it easy to break into the pre-existing spheres of influence - of the Anglo-Americans in East Africa, France in the Western Indian Ocean and India in South Asia. It is no surprise then themes of non-intervention and sovereign equality found much prominence in Wang's visit to the Indian Ocean littoral.

Although the US and India have many strengths in the Indian Ocean, their task in matching the Chinese outreach in the littoral is growing harder by the day.

Related: Maldives: Even a tiny state in the Indo Pacific has a big role in China-US competition | Indo-Pacific: Central theatre of America's struggle against its antagonist, China | With China's increasing assertiveness, India's active role in the Indian Ocean matters more than ever | India in the Indo-Pacific: Reining in China in the new theatre of great power rivalry