China's 'latte art' from a thousand years back

(Photos provided by Cheng Pei-kai unless otherwise stated.)

A group of us from the China Folklore Society was in Changzhou to study the city's intangible cultural heritage. I arrived later than the others, missing the main activities of the first day. But I did manage to make it to the last pitstop before dinner: the Former Residence of Lü Gong (吕宫府), located in the city's historical and cultural district. At this former abode of Qing dynasty scholar Lü Gong (吕宫), ancient literati pastimes such as pingtan (评弹, a form of musical storytelling), poetry reading, calligraphy, incense appreciation and tea drinking come to life.

Situated in Changzhou's city centre, the Former Residence of Lü Gong was originally part of the ancient architectural complexes of the Ming and Qing dynasties. Over a decade ago, Changzhou destroyed various cultural relics and historical sites in the name of urban renewal and building a business district. Lü Gong's former residence was one of the lucky heritage sites to have escaped demolition.

Where the literati chose to spend their idyllic days

A friend once told me that Song dynasty poet Su Shi chose to spend the rest of his days in Changzhou after his release from exile in Hainan. He passed away in Changzhou's Tenghua Jiuguan (藤花旧馆, lit. the Old Museum of Wisteria). But it appears that the site did not escape the fate of modernity and was brutally demolished before it was later rebuilt. Because of my late arrival in Changzhou, I didn't get to see the new Tenghua Jiuguan and do not know how much sentiments from Su's times have been preserved.

However, Su lived a tumultuous life and was frequently demoted and exiled. The imperial court had "graciously granted" him permission to live in Changzhou, where he had a period of idleness. During the Song dynasty, Changzhou included the regions of Wujin, Wuxi, Yixing, Jiangyin and Jingjiang.

Written by Su in 1084, the ci (词, a type of lyric poetry) "Pusa Man (菩萨蛮)" talks about life in Changzhou's Yixing, or what's known as Yangxian (阳羡), back then. In the lyric poem, Su said that he had chosen to settle down and buy a field in Yangxian in his old age because of its beautiful landscape. He would travel around in a boat and be embraced by the wonders of nature. He was tired of officialdom and yearned for a carefree life in the fields.

Two years later, he returned to politics and visited Changzhou again in the early spring, excitedly writing the famous poem on a painting (《惠崇春江晚景》): "A few branches of peach blossoms have just bloomed outside the bamboo forest. The ducks waddling in the water know first when the river becomes warm in spring. Chinese mugwort fills the river bank and reeds are sprouting. Pufferfish are now swimming against the current, returning to the river from the sea."

Although I did not get to see Su's newly restored former residence, I was content with the fact that I had come to a place so loved by Su, and was about to eat the pufferfish that he so yearned for that night.

Reliving the artistry of diancha

By the time I reached the Former Residence of Lü Gong, the group was done learning about incense and drinking tea and most of them were rather restless. But when Wang and Ji heard that I had arrived, they excitedly exclaimed that the tea expert was here and asked me to try the tea-brewing technique of diancha (点茶), which was used during the Song dynasty.

A friend of mine from the intangible cultural heritage centre in Nanjing studies diancha. In the Song dynasty tradition, he would grind the tea powder finely before adding them to a black porcelain tea bowl, add water and use a bamboo whisk to mix the concoction into a thick, pale green froth.

Ji is a renowned Changzhou calligrapher. He picked up a long bamboo stick and used it as a brush, dipping it into the vibrant green tea paste and actually dot-painting a bamboo forest.

Ji is a renowned Changzhou calligrapher. He picked up a long bamboo stick and used it as a brush, dipping it into the vibrant green tea paste and actually dot-painting a bamboo forest. He complained as he painted, saying that the tea foam made the brush sticky, so he couldn't paint in continuous strokes and could only create dots.

We told him that he was doing a good job, and encouraged him to draw plum blossoms next. He dot-painted plum blossoms on a rock, and the finished product somehow exuded the aura of plum blossoms blooming during winter in a barren landscape. Everyone praised his masterpiece.

During the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, historian Tao Gu collated Qing Yi Lu (《清异录》, a short encyclopedia). The anthology included the tale of a monk named Fuquan (福全), who could write poems on tea foam. With four tea bowls placed side by side, he was able to write a line of poetry in each cup, forming a Chinese quatrain (绝句). He became famous for his unique skill, attracting a massive crowd who wanted to watch him work his magic. Fuquan later laughed at himself saying it was a pity he could not compete with Tang dynasty Tea Sage Lu Yu to see if his tea foam-writing skills surpassed Lu's tea-brewing skills.

The book Qing Yi Lu further explains that people back then called this extraordinary skill of writing or drawing on tea foam chabaixi (茶百戏, lit. "a hundred tricks with tea", an ancient art form that involved drawing on the frothy surface of tea).

I wonder if the ancient Chinese also used bamboo sticks to write poems or make paintings on tea? Or did they use an ink brush dipped in ink to display their calligraphy skills on tea foam?

Modern literati and a tribute to the old Masters

Although the artistic effect of painting on tea foam is certainly miles apart from making art on Xuan paper, there is something novel and admirable about Ji's skill, which I think is not inferior to the monk Fuquan. I wonder if the ancient Chinese also used bamboo sticks to write poems or make paintings on tea? Or did they use an ink brush dipped in ink to display their calligraphy skills on tea foam?

In our minds, whichever writing tool the ancients used, writing poetry or painting on tea was an unbelievable skill or even a miracle. Since Ji mastered the skill and even showed us the mystery of Song dynasty's chabaixi, I was deeply impressed and inspired.

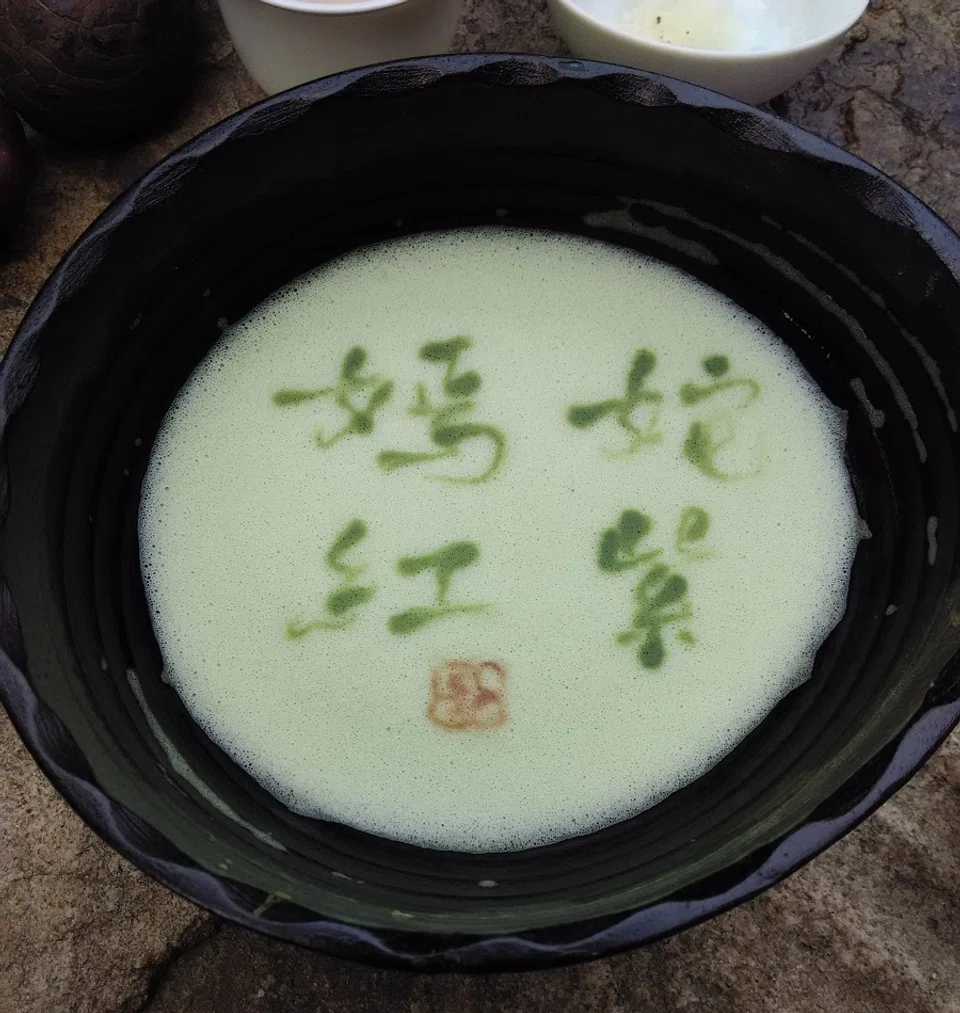

After Ji finished drawing the plum blossoms, he asked if I would like to add a few words to the painting. Everyone agreed, saying that the calligrapher ought to leave his mark on the tea foam, counting it as offering incense to Lu Yu. So, I picked up the bamboo stick, dipped it in the thick tea paste, and wrote the words "姹紫嫣红" (Cha Zi Yan Hong, meaning "beautiful flowers in vibrant colours") on the newly-whisked tea froth.

Just as Ji had said, the tea foam was incredibly sticky and I couldn't make continuous strokes. I could only go back and forth between writing and stopping, sometimes managing a stroke and other times making a dot, finally piecing my words together.

My friend from Nanjing concocted another reddish-brown tea paste, and said that I could use it to draw a Chinese seal. So we adopted his idea and drew a small, square seal on the tea foam. The finished piece could indeed pass for a chabaixi. Although Su Shi would have probably found it unsightly, I guess it could perhaps compete against Fuquan's work.

This article was first published in Chinese on United Daily News as "茶百戲" in 2016.

Related: A taste of Changzhou: Best from the rivers and lakes | The power of food memories in shaping who we are | Hong Kong's intangible cultural heritage and the preservation of Lingnan culture | Song dynasty poet Su Shi's appetite for exotic foods | More than one road to 'the way of tea' | Popular in the Ming and Qing dynasties, will Songluo tea make a comeback? | Pu-erh: The raw, the ripe and the Qing dynasty 'tribute tea' from Yunnan