China's massive north-south gap in the cultural and economic realms

Following the close of Chunwan (春晚, CCTV's New Year's Gala) and various cheers and jeers that followed, a friend sent me an article discussing the audience analysis of the event, sighing, "Wow, I didn't know a north-south divide could be read from the New Year's Gala."

According to statistics from we-media, Chunwan, a programme that airs on Chinese New Year's Eve every year, had the highest audience rating (80%) in the three northeastern provinces. But moving southwards, people's interest in Chunwan began decreasing, particularly in the regions south of the Yangtze River, where audience ratings were less than 20%. In the provinces of Guangdong and Hainan, audience measurements were in the negligible single digits.

Some have since concluded that the Chinese enthusiasm towards Chunwan decreases in a North-South pattern from "Must watch!", "Can watch", and "Seldom watch..." to "What is Chunwan?".

Different cultural norms and language use

I went online to try and understand the differences in Chunwan audience measurements between the North and South. In a country as big as China, there are massive regional differences in Chinese New Year customs between the northern and southern regions. But Chunwan mainly showcases the customs of the northern regions, such as cooking and eating dumplings during Chinese New Year. While these are familiar customs in the north, they are irrelevant to people in the south who eat tangyuan (glutinous rice balls) and nian gao (rice cake) during the festive season.

Furthermore, as Chunwan is presented from a northern cultural perspective, language-based segments such as crosstalks and sketch comedies are the main highlights of the show. But crosstalk originated and flourished in the Beijing and Tianjin area, while sketch comedy has long been performed by errenzhuan (二人转, lit. two-people rotation) actors from northeast China. Thus, such programmes are not well-received in the south due to differences in culture and language use. Southerners are often confused by the "jokes" that northerners are able to understand and laugh at. According to a thread on Chinese question-and-answer website Zhihu discussing the reasons why people from Guangdong do not watch Chunwan, a netizen bluntly put: "I really cannot understand the content!"

Unlike people who endure the chilly weather in the north during the Chinese New Year season, people in the south where the temperatures are warmer have more options when it comes to celebrating Chinese New Year's Eve. Most of them would not stay at home and watch TV, but would instead head out to look at the flowers and the lights, or have a meal, watch a movie, and play mahjong with friends and family.

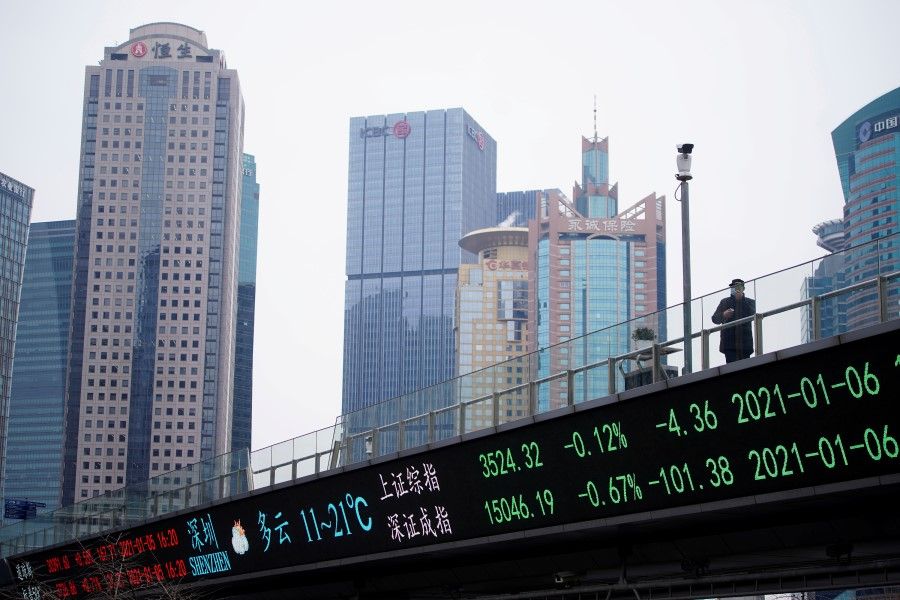

According to the 2020 GDP data released last month, of China's top ten cities that displayed the best economic performance, Beijing is the only northern city on the list.

North and south: a tale of two regions

The north-south divide in Chunwan audience ratings also reignited public debate about the age-old topic of China's north-south economic imbalance.

Whenever China announces its regional GDP at the beginning of each year, the gap between China's north and south would always be speculated on. This year is no exception. According to the 2020 GDP data released last month, of China's top ten cities that displayed the best economic performance, Beijing is the only northern city on the list.

The stronger development in southern China as compared to the north has become increasingly obvious over the 40 years of China's reform and opening up. In 1978, cities in northern China made up over half the list of the country's top ten cities with the strongest economies. However, with the rise of "southern stars" such as Shenzhen, Hangzhou, and Suzhou, northern cities such as Harbin, Qingdao, Dalian, and Shenyang dropped out of the list, leaving only Beijing and Tianjin. And in the third quarter of last year, Tianjin was squeezed out for the first time, leaving just Beijing as the sole northern city on the list. Many industry players also believe that if the serious GDP "inflation" in some northern provinces had been discovered sooner, any correction might have led to a larger gap between the north and south appearing even sooner as well.

Without the burden of a planned economy, private enterprises in the south thrived, and the region became significantly more economically vibrant and diverse than the north.

There is a saying in China's investment sector to describe the country's uneven regional development: "Investments do not go beyond Shanhaiguan (山海关)." Shanhaiguan District is located in Qinhuangdao city in Hebei in northeast China, named after the Great Wall's Shanhai Pass; the half-joking saying means that investments do not go to the northeast areas, and is an expression of investors' concern about the poor business environment and general lacklustre economy in northeastern China.

After Tianjin was squeezed out of the top ten list last year, even Shanhaiguan started to seem far for investors, who came up with a new saying that "investments do not make it beyond the map of the Southern Song dynasty", whose territory was historically in southeastern China.

This phenomenon of "strong south, weak north" is an extension of the transition between old and new economies in China. In the early years, the northern regions with heavy industries and state-owned enterprises as the main economic pillars did once have a booming manufacturing sector. However, following China's reform and opening up, the southeastern coastal areas held a geographical advantage and quickly connected with the rest of the world. Without the burden of a planned economy, private enterprises in the south thrived, and the region became significantly more economically vibrant and diverse than the north.

North needs to step up on market reform

The different culture in the south has also led to better conditions for creating a market-friendly business environment. Having been posted to China for the past few years, I have had the opportunity to go to various provinces such as Liaoning, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Guangdong for work. Even though my short stints have only allowed me to scratch the surface of various cities, my limited exchanges with the locals have still given me a sense of the different mindsets and local cultures in China. Northerners are more rough and gregarious - they value loyalty, relationships, and connections; southerners are sharp and pragmatic to the point of seeming cold and ruthless at times, but they play by the rules and stick to contracts, so that social connections are far less important in the south than in the north.

If the organisers of Chunwan want more people to tune in to the annual event that they have painstakingly put together, they will have to start with viewers in the south.

The gap between the north and south has gained attention in China. Even the ratings for Chunwan also reminds one of the vast difference between the economies in the north and south, highlighting the worrying imbalance in regional development. Over the past few years, the southward flow of people, as well as investments to where the new economy keeps springing up, has made it more difficult to break the cycle of the widening gap between north and south. Ren Zeping, dean of the Evergrande Research Institute at Tsinghua University, wrote in a recent commentary that the widening gap between north and south is a victory of the market economy over the planned economy, showing the necessity and urgency for the north to step up on market reform.

If the organisers of Chunwan want more people to tune in to the annual event that they have painstakingly put together, they will have to start with viewers in the south. And if China wants to move into a new stage of development with common prosperity and resolve the problem of unbalanced and insufficient development, it seems it will have to start with the northern regions that are lagging behind.