Chinese economics professor: Why we exchange gifts, from ancient China to the present

Receiving gifts from relatives and friends during the Lunar New Year is inevitable. True enough, a friend from northern China brought us a gift when he visited us this year. After our guest left, my children were curious to find out what was inside this box labelled "local specialties". They eagerly unboxed the gift.

"Oh, just a box of noodles," they said as they lost interest and skipped away.

My wife is a southerner and likes nian gao (年糕) or rice cakes. She is not very fond of noodles. Although I am a northerner, I've been listening to advice from weight loss gurus recently and am worried that noodles will make me put on weight. Naturally, I'll be giving the noodles a pass. Looks like we can only give this box of noodles to someone else.

"Wouldn't it be better to give cash? Or directly convert this box of noodles into money? What can't be bought online nowadays?" I said grumpily, guided by the logic of economic thinking.

"But they can also convert the time spent choosing a gift into money! Besides, how better can you show someone you value them than by giving them money?" my economic mind whirred again.

The economics of gift-giving

To economists, gift-giving is really befuddling. Why do people head to the malls to buy merchandise as gifts instead of giving cash directly? Cash is money; it is kong fang xiong (孔方兄, a bronze coin with a square hole in the centre) and e du wu (阿堵物, an ancient way of referring to money) - who does not know this? Throughout the ages, this is what everyone wants!

My wife thought for a moment and said, "Maybe it's because buying a gift takes time and this shows that they value the other party a lot."

"But they can also convert the time spent choosing a gift into money! Besides, how better can you show someone you value them than by giving them money?" my economic mind whirred again.

Whenever this happens, my wife usually ignores me and busies herself with other things.

I can make these arguments with confidence because it is based on what a world-class economist said in an article published in one of the most renowned economics journals in the field.

In his 1993 article "The Deadweight Loss of Christmas" in the American Economic Review, Yale University economics professor Joel Waldfogel said that holiday gift-giving is a "potential source of deadweight loss" as gift-giving destroys between 10% and a third of the value of gifts.

The term "deadweight loss" was invented by economists to measure the efficiency of resource allocation. They first came up with an ideal economic state, known as "Pareto optimality". In this state, all individuals have achieved welfare maximisation. If an individual's well-being can still be improved through a reallocation of resources, then Pareto optimality has not been achieved. If an activity not only fails to improve welfare, but also deviates from the optimal state, then that would result in a deadweight loss of welfare.

Based on this definition, holiday gift-giving could be a behaviour that deviates from Pareto optimality and leads to deadweight loss.

But if your friend thinks that the gift is worth 100 RMB and you think that it is only worth 50 RMB, that would be a mismatch.

To write this article, I specially downloaded this famous academic paper. Prof Waldfogel's paper is concise - it is a mere nine pages, including tables and references - but it packs a punch. Compared with economic papers nowadays that are hundreds of pages long, this pithy piece is very appealing. The paper has a classic structure, containing an argument, data, empirical analysis, and welfare estimates. It was published in December 1993 - perhaps the editors liked the article too and thought that it was very interesting and decided to publish it during the Christmas season.

Prof Waldfogel began his paper by saying that when economists talked about holiday gift-giving in the past, it was usually to "condone the healthy effect of spending on the macroeconomy". But in fact, the consumer behaviour of gift-giving is such that "consumption choices are made by someone other than the final consumer", which results in a mismatch with the recipients' preferences from a microeconomic perspective. In other words, there is a mismatch between the true consumer and the consumer product, which could result in what happened to my family above.

If a friend thinks that the gift he or she gave you was carefully picked out and is worth 100 RMB, and if you feel the same way as well, then the gift is not a mismatch with its recipient. But if your friend thinks that the gift is worth 100 RMB and you think that it is only worth 50 RMB, that would be a mismatch. When that happens, it may be better if the gift was not given to you but was kept and consumed by your friend instead. But since the gift has been given to you, it has resulted in a deadweight loss of 50 RMB.

Honestly, although this paper was published 28 years ago, Prof Waldfogel's straight-shooting prognosis still made a lot of sense despite the distance of time, a computer screen and the internet. So I started paying more attention to gifts and looking up reference material including works by academics in other fields.

Returning a gift, even to those you detest

In fact, ancient people in China placed much importance on gift-giving. Isn't there a saying that goes, "To receive and not reciprocate is impolite" (来而不往非礼也)? A story of gift-giving is also recorded in The Analects: Yang Huo (《论语·阳货篇》)*: "Yang Huo wished to see Confucius, but Confucius would not go to see him. On this, he sent a present of a pig to Confucius, who, having chosen a time when Huo was not at home, went to pay his respects for the gift. He met him, however, on the way. Huo said to Confucius, 'Come, let me speak with you.' He then asked, 'Can he be called benevolent who keeps his jewel in his bosom, and leaves his country to confusion?' Confucius replied, 'No.' 'Can he be called wise, who is anxious to be engaged in public employment, and yet is constantly losing the opportunity of being so?' Confucius again said, 'No.' 'The days and months are passing away; the years do not wait for us.' Confucius said, 'Right; I will go into office.'"

Put plainly, this is the story of a person named Yang Huo who wanted to visit Confucius but the latter did not want to see him. Yang gave Confucius a small steamed pig as a gift. Confucius was strange as well; he purposely went to Yang's house to thank him for his gift when Yang was out. Alas, Confucius met Yang while on the way to his house and was chided by Yang. Confucius said that he was going to become a court official, even though he did not in the end.

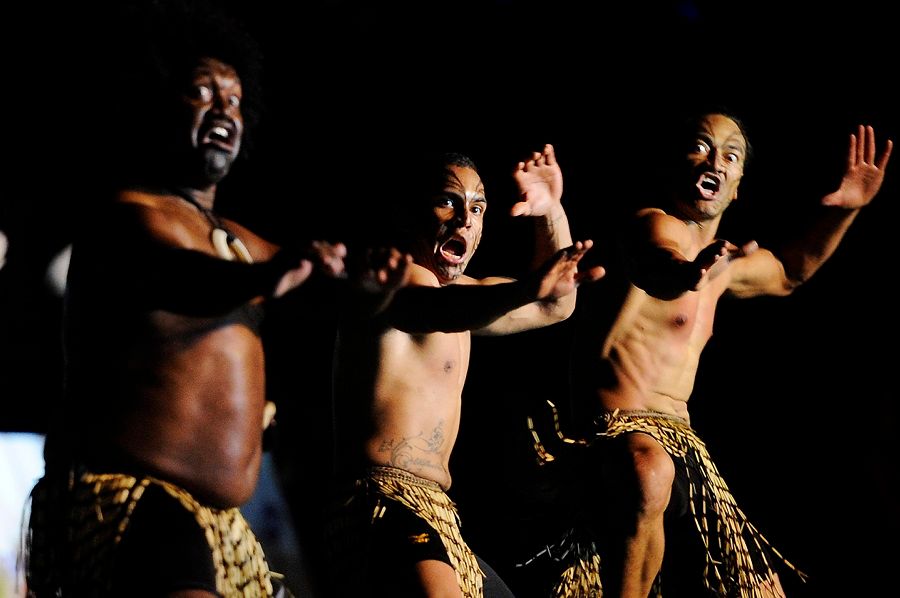

Yang Huo, also known as Yang Hu, was not a good person. He was a vassal of Ji Pingzi, a chief minister of the regional state of Lu during the Spring and Autumn period. Several generations of the Ji clan had controlled the state of Lu, which infuriated Confucius, who said that there was nothing they dared not do since they were already bold enough to engage a group of 64 musicians and dancers - a number reserved for the emperor - to entertain themselves in their homes. Furthermore, Yang was also in charge of the household affairs of the Ji family. Following the death of Ji Pingzi, Yang was even involved in killing Ji Huanzi, his master and the son of Ji Pingzi, and had free rein over Lu's political affairs. It was only natural that Confucius did not want to associate himself with a traitor like Yang.

But regardless of how unwilling he was to be associated with Yang, Confucius still needed to express his gratitude for Yang's gift and this is where the story becomes interesting - there must be some deeper meaning behind the social mores of gift-giving.

In northern Chinese villages, people visit their relatives during the Lunar New Year, and the gifts they usually bring on these visits are steamed buns.

Necessary, but not necessarily equal

Professor Yan Yunxiang of the University of California, Los Angeles' Department of Anthropology once studied Heilongjiang's Xiajia village (下岬村). He discovered that gift-giving was a major sociological phenomenon in all aspects of social life in northern rural communities. Further, he identified 21 gift-giving behaviours in the village and explored the relationship between gift-giving and the building up of interpersonal networks. He did this by analysing extensive gift exchanges within the village and the moral considerations driving villagers to take part in such activities. The local rules for the exchange of gifts shed light on the complexity, flexibility and context of the villagers' way of life. From Prof Yan's research, the moral and emotional aspects of interpersonal relationships as represented by gifts explain renqing (人情, favour, human relationships) as an ethical system based on common sense.

Next, Prof Yan talked about an experience that had also left a deep impression on me when I was a kid. In northern Chinese villages, people visit their relatives during the Lunar New Year, and the gifts they usually bring on these visits are steamed buns. In particular, the buns given to the elders must be huge in size. When a family welcomes a new baby girl, people would congratulate the family and say that they have given birth to a "huge bun" (大馍), meaning that when the daughter grows up and returns home to celebrate the new year in the future, she must give her parents a huge bun in return. But because the bun is simply too huge, they are often undercooked. And because my grandmother spent the new year at my house every year, her daughters and granddaughters would all arrive bearing massive steamed buns as gifts.

The next two or even three months after the new year were always the toughest time of the year for me - my family had to eat undercooked steamed buns for as long as three months! On the other hand, my mother made huge quantities of steamed buns topped with red dates using much finer flour as return gifts. As my mother's steaming technique is better, our steamed buns were absolutely delicious. But they were all given away as return gifts - how sad! Because of these nightmarish memories, I could identify with Prof Yan's research even more.

Renowned French sociologist Marcel Mauss wrote his masterpiece on sociology entitled The Gift. This was his central research question: "What rule of legality and self-interest, in societies of a backward or archaic type, compels the gift that has been received to be obligatorily reciprocated? What power resides in the object given that causes its recipient to pay it back?" This is also the question I asked myself when I was young, and is also the exact reason why Confucius had to reciprocate Yang's gift back in the day.

... in gift-giving, the giver does not only give a gift, but also gives a part of himself to the receiver; to give something is to give a part of oneself.

Mauss' answer was inspired by a Maori notion that the spirit of the giver - hau - is present in the gift. This is a type of spirit that can redeem and also hurt - it can even kill people who receive gifts but do not reciprocate. To Mauss, the ancient world was an entirely personal world. He came to the conclusion that, in gift-giving, the giver does not only give a gift, but also gives a part of himself to the receiver; to give something is to give a part of oneself.

In fact, Mauss' masterpiece based on the study of ancient Scandinavia, Northwest America, and Melanesia tells us that human society originally had no market and no concept of buying and selling, mutual exchange, or bartering. Even contracts were non-existent. In this sense, the world of markets and contracts on which economics is based was not a predominant characteristic throughout human evolution.

So then, since these things were non-existent, what did human society have at that time?

Gifts.

----------------------------

This article was first published in Chinese by Caixin Global as "神奇的生活经济学:经济学直男不要礼物要红包". Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

*Translation by James Legge at Chinese Text Project.