Covid-19: Can the global economy operate without China? [Part Two]

A jolt to the world's oil industry

On 3 February, the price of London Brent crude oil plummeted by 3% to US$54.27 per barrel, below the US$55 mark. Then on 10 February, Brent crude fell again to US$53.27 per barrel, while West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil futures prices on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) fell below US$50 to $49.57 per barrel, marking new lows in over a year. (NB: The latter has since risen to approximately $53.)

The drop of 3 million barrels a day in China translates to more than 3% of global oil consumption, which is a jolt to the world's oil industry.

In the month or so since Covid-19 gained attention, international oil prices have fallen by nearly 25%, for just one reason: the outbreak has led to a huge drop in China's demand for crude oil. Leaders in China's energy industry forecast that China's demand for crude oil will fall by 25% year-on-year. According to figures from the International Energy Agency (IEA), Chinese oil demand in February 2019 was just under 13 million barrels a day, meaning this figure will fall by 3.2 million barrels a day in February 2020.

China is currently the world's second largest oil consumer behind the US, and the world's largest oil importer. The drop of 3 million barrels a day in China translates to more than 3% of global oil consumption, which is a jolt to the world's oil industry. Analysts believe that this impact on demand might be even worse than during the 2008 global financial crisis.

BP chief financial officer Brian Gilvary said on 4 February that he thinks this epidemic will lead to a drop of 40% in global oil demand this year, or about 500,000 barrels a day. But according to initial estimates from BP and other global energy groups, global oil demand in 2020 is set to grow by 1.2 million barrels a day as compared to 2019.

A Financial Times report last week said major Chinese energy companies such as China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), Sinopec, and China National Petroleum Corporation, may be considering invoking force majeure to halt contracts for liquefied natural gas (LNG). These companies have not responded. This would be a case of "it never rains but it pours" for LNG suppliers. With warm winters and increased production in countries such as the US and Australia leading to a general oversupply, Asia's LNG prices were already at a record low, with a further drop of 40% in the first month or so this year following the epidemic. (NB: Latest reports say that CNOOC has since invoked force majeure, but this has been rejected by both Shell and France Total.)

There may be some legal debate over whether this epidemic would come under force majeure, but with China being a major consumer and poised to quickly become the largest consumer, international LNG sellers may have to be flexible.

One financial analyst said, "This is the worst crisis to happen in the worst time and place for the oil market."

This is true, because international oil prices are weak now. The oil-producing countries in OPEC and some non-members including Russia (OPEC+), reduced production in January this year. Last week, OPEC+ began emergency talks with China to assess the impact of the epidemic on oil demand and how to respond.

One important basis of the deal is that China buys US$200 billion worth of US goods in the next two years. But the first thing hit by the epidemic is consumption.

Crude oil is just one international commodity that has been affected by the epidemic. In fact, from iron ore to copper, agricultural products, coal, zinc, and palm oil, all industrially produced commodities are impacted.

US-China phase one trade agreement up in the air

The epidemic might also make it more difficult for China to meet the terms of the first phase trade agreement signed with the US in mid-January. One important basis of the deal is that China buys US$200 billion worth of US goods in the next two years. But the first thing hit by the epidemic is consumption. If China's domestic retail market shrinks because of the epidemic and remains low, it might be difficult to consume that much worth of US goods, especially US$32 billion worth of agricultural products.

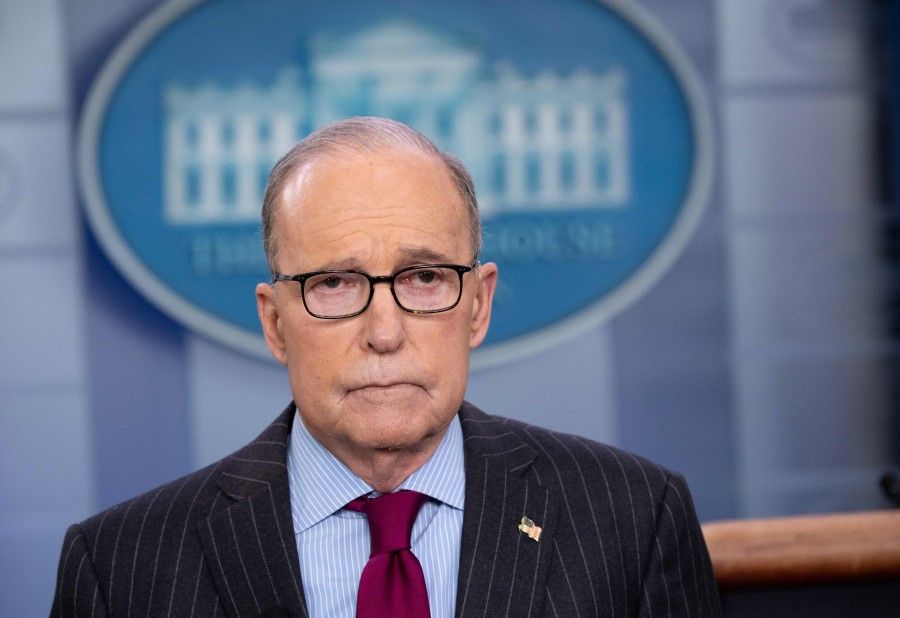

US National Economic Council director Larry Kudlow made it clear in an interview last week that the US will not use the epidemic's impact on China as leverage for the second phase of trade talks. On the contrary, the US is prepared to work with China to provide humanitarian aid. He also believed that while the epidemic might create some uncertainty, the phase one agreement will bring growth later this year.

However, Kudlow also admitted that the epidemic might mean China will push back its purchase of US$200 billion worth of US goods according to the phase one deal, and the "export boom" for the US will be delayed. Even though he foresees that the crisis will have no major impact on the US economy, US economic growth in the first quarter of this year will take a hit of about 0.2%.

However, several economic analysts remain worried about whether China will be able to keep its word as scheduled. A report from the US Department of Agriculture on 7 February shows that as of the week of 30 January, the US exported just 31,523 tonnes of soybeans to China, the lowest volume since the week of 5 September 2019.

If the US on the other side of the Pacific can feel the effects of the drop in China's demand caused by the epidemic, all the more those countries that depend on China's demand for commodity exports. So, this trend will have a major impact on the global commodities market including energy, and directly affect the economic outlook of these countries that export commodities.

When China coughs...

Right now, nobody can say for sure how heavy the impact will be on global economic growth in 2020. That depends on how quickly the epidemic is brought under control. But the damage has been done and the short-term impact is especially heavy. Furthermore, even if the epidemic is easily controlled, the economic recovery over the rest of the year will not make up for the whole of these short-term losses.

In 2003, China's GDP was just over 4% of global GDP. In 2019, that share had grown to 18%. China's role in the global economy has also changed.

The spillover effect of Covid-19 on the world economy is unquestionably greater than during SARS in 2003. SARS killed about 800 people and resulted in a loss of about US$40 billion for the global economy, leading to a drop of 0.1% in global economic growth that year. Covid-19 has already infected over four times the number of people as compared to SARS. It is also not as serious as SARS, but more people have died from it already.

More importantly, the scale of China's economy has changed. In 2003, China's GDP was just over 4% of global GDP. In 2019, that share had grown to 18%. China's role in the global economy has also changed. Today, China is at the centre of the global supply chain, exporting the most products and tourists to the rest of the world. If China was running a fever during SARS in 2003 and the world started sneezing, then in 2020, if China is coughing because of Covid-19, the world will come down with a fever and an even greater illness.

There have been warnings that Africa may be an Achilles heel, as China is currently the largest investor in that continent, and millions of Chinese work in Africa.

Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), recently said she was worried that the epidemic in China might depress the global economy this year - the IMF originally forecast 3.3% growth in the global economy in 2020. In its recent forecast, Goldman Sachs said if the epidemic is rapidly controlled and slows in February or March, global GDP growth will slip by 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points in 2020, but if the epidemic peaks only in the second quarter, the drop will be 0.3 percentage points.

Of course, each country is impacted differently.

An exercise in preparation for China's decoupling and deglobalisation

Asian countries, including Australia, are near China, and are most economically dependent on China. Covid-19 will have the biggest impact on them. Also, some small Asian economies are weak and not able to handle risk. In comparison, large Western economies will not feel the impact so much. As Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell and Kudlow optimistically forecast several times, growth in the US, UK, and Eurozone is expected to drop by about 0.1 percentage points. Germany might be an exception, with possible loss of 0.2 percentage points due to its large exports to China.

But these forecasts assume the epidemic is confined to China and that it is eventually brought under control. If it becomes a pandemic and spreads beyond China, the consequences will be serious. This is especially true for nations with a weak economy and a poor sanitary system, but a strong link to China. There have been warnings that Africa may be an Achilles heel, as China is currently the largest investor in that continent, and millions of Chinese work in Africa.

Georgieva has made a strong call to central banks to support the world economy by continuing to maintain a relaxed currency policy in 2020, even if it has already led to high debt.

To summarise, Covid-19 will spill out of China and affect the global economy in three ways. First, shrinking tourism, consumer market, and goods transportation with China due to travel and transport restrictions. Second, China's economic standstill has led to a sharp drop in China's domestic demand, which has heavily impacted global commodities markets. Finally, and most broadly, the long pause has led to a tightening and even partial paralysis of the China-centric global production supply chain, which in turn has caused a chain reaction and unprecedented chaos in the global industrial chain.

This also means that China's dominant role in the global supply chain may be weakened.

I foresee that the toughest test might come in those countries that are heavily dependent on petroleum gas exports, such as Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. Their national finances will take a catastrophic hit due to the drop in oil exports and prices, which will have a direct impact on the people and the political stability of these countries.

China is a major world economy that will not be brought down by an epidemic. But on deeper thought, the chaos created in the supply chain by this epidemic has highlighted China's important role as a node in the global manufacturing industry, and also exposed the risks and challenges behind these advantages. We can see this epidemic as an exercise in preparation for China's decoupling and deglobalisation, and see what the world economy would be like if there was real decoupling with China.

In the short to medium term, an epidemic will not lead to major adjustments and changes in the global supply chain, and China's status will not be taken over by a country or countries for some time. After the epidemic dies down, these supply chains will gradually recover. But in the long term, calls for greater diversification of supply chains will be one thing that economic policymakers seriously consider. This also means that China's dominant role in the global supply chain may be weakened.

Related reading: Covid-19: Can the global economy operate without China? [Part One]

This article was first published in Chinese in The Economic Observer (经济观察报).