Did Mongolians mistreat the Han Chinese during the Yuan dynasty?

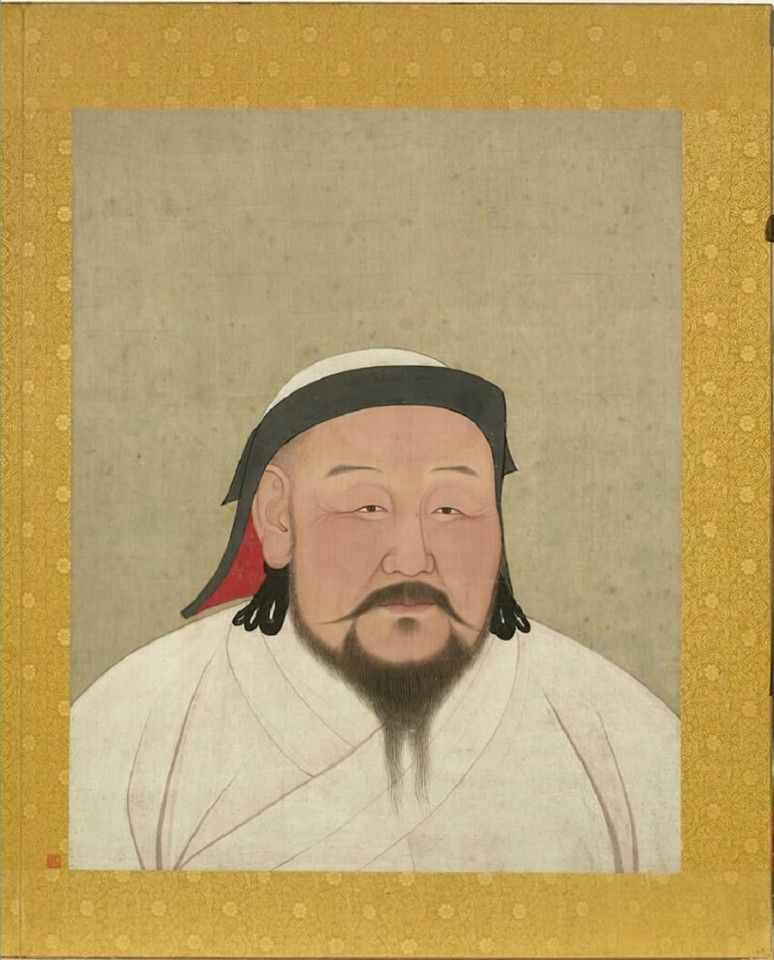

In childhood history classes, I learnt that during the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty, the Mongols despised and suppressed the Han people, dividing the population into four classes according to ethnicity: the Mongols (蒙古), the Semu (色目), the Han people (汉人) and the Southerners (南人).

As conquerors, the Mongols were naturally at the top. Then came the Semu - various ethnic groups who were not part of the Han people. The third class were the Han people who had accepted Mongol rule before the latter's conquest of the Southern Song, and the lowest class were the Han people in the south who were subjects of the Southern Song before being conquered by the Mongols.

I didn't know much about culture and history when I was little and thought that Semu meant "coloured (色 se) eyes (目 mu)" and so must refer to Caucasians with blue, green, grey or brown eyes. However, mu in this case does not refer to "eyes" but something like "catalogue" (目录 mulu) or "category" (类目 leimu) - thus, Semu should be understood as "an assortment of ethnic groups".

Subtle suppression during the Yuan dynasty

But it made no difference to us primary school children who learnt history from textbooks. We just knew that the Mongol-led imperial dynasty despised the Han people, especially those from the south. This reflected the foreign domination of China and the brutal suppression of the Han people. Much like how white Americans had enslaved blacks in the past, the Han had absolutely no social status, let alone a foothold in the imperial court.

On the contrary, I discovered that many Han people held important positions in the Mongol government and steadily rose through the ranks.

When I got older and delved into Yuan dynasty historical literature and literary works, I could not find any information about the official laws of the "four-class system" (四等人制). Even in texts and works by "oppressed Southerners" from the Yuan dynasty, I did not find any record of this segregation policy either.

On the contrary, I discovered that many Han people held important positions in the Mongol government and steadily rose through the ranks. I couldn't help but wonder if the so-called "racial discrimination" under Mongol rule was simply a "kinship" practice of the Mongols, similar to the Han people's "differential mode of association" (差序格局, chaxu geju), as proposed by the Chinese sociologist Fei Xiaotong, which is centred on family kinship.

In the actual workings of society, the Mongols and the nomadic people were favoured while the outsiders (the conquered Han people, the Southerners and the Koryo people) were sidelined. However, there was no actual law enforcement. This is similar to the concept of the old boy network or nepotism, and is different from the apartheid policies of the US and South Africa in history, which systematically discriminated against and oppressed people of colour with a series of stringent laws and enforcement.

Academics pointed out that the term "four-class system" originated in late Qing dynasty scholar Tu Ji (屠寄)'s book The History of the Mongols (《蒙兀儿史记》), which said that the Yuan dynasty adopted strict racial boundaries with people clearly divided into four classes: the Mongols, the Semu, the Han people and the Southerners.

Image of Mongols and their 'barbaric regime'

Influenced by modern Western nationalist ideologies, scholars in the late Qing dynasty and early Republic of China (ROC) era felt great antagonism towards foreigners; they viewed Mongol rule as a barbaric regime dedicated to the oppression of the Han people, which led to the widespread mention of Yuan dynasty's four-class system.

History textbooks from the ROC era, such as Chinese historian Qian Mu's A General History of China (《国史大纲》) and Fan Wenlan's The Concise Edition of General History of China (《中国通史简编》), recorded the system of the Yuan dynasty, which then became part of our historical knowledge.

The term "Confucian scholars the ninth and beggars the tenth" (九儒十丐) - meaning Confucian scholars were ranked only above beggars during the Yuan dynasty - is used as another historical evidence that the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty was barbaric and ignorant; it brutally trampled on the land of China and had a contemptible social system.

Since I was little, I have often heard that the Mongols were an uncultured people who divided people into ten classes based on their occupation.

Chinese historian Fan Shuzhi writes in the 2021 book Illustrated History of China (《图文中国史》): "The Mongol nobility originated from the north of the Gobi desert and were only adept at hunting. They neglected the imperial examinations and even abolished them for nearly eight decades. The status of Han intellectuals fell to an unprecedented low.

"According to records back then, the Han people were divided into ten classes: first, high officials (官); second, petty officials (吏); third, Buddhist monks (僧); fourth, Taoist priests (道); fifth, physicians (医); sixth, artisans (工); seventh, hunters (猎); eighth, prostitutes (娼); ninth, Confucian scholars (儒); and tenth, beggars (丐). The Confucian scholars (intellectuals), who have always taken it upon themselves to serve the country and the people, were actually ranked ninth, merely below prostitutes and above beggars."

'Historical reality' questionable

This classification was taken as a historical fact. But is this really true?

[They] were vestiges of the Song dynasty who had been loyal to the Song imperial court. While their indignation was real, whether their sentiments reflect "historical reality" is another question.

Qing dynasty scholar Zhao Yi (赵翼) had long pointed out in chapter 42 of his academic notes (《陔余丛考》) that this was but a popular belief and not a law enacted by the imperial court. He wrote: "Xie Dieshan Ji (《谢叠山集》) quoted Song Fang Bozai Xu (《送方伯载序》) as saying, 'Ordinary folks are categorised into ten classes: first, high officials and second, petty officials (吏); these people are noblemen. Seventh, carpenters (匠), eighth, prostitutes, ninth, Confucian scholars, and tenth, beggars; these people are the lowly ones.'

"Zheng Suonan Ji (《郑所南集》) also says: 'Based on the Yuan dynasty system, the ten classes are: first, high officials; second, petty officials; third, Buddhist monks; fourth, Taoist priests; fifth, physicians; sixth, artisans; seventh, hunters; eighth, ordinary workers (民); ninth, Confucian scholars; and tenth, beggars.' There is no mention of carpenters the seventh or prostitutes the eighth. Since the beginning of the Yuan dynasty, this is how the people were roughly categorised according to observations. It is not an imperial decree."

Zheng Sixiao (郑思肖), author of Zheng Suonan Ji, and Xie Fangde (谢枋得), author of Xie Dieshan Ji, both of whom had mentioned the concept of "Confucian scholars the ninth and beggars the tenth", were vestiges of the Song dynasty who had been loyal to the Song imperial court. While their indignation was real, whether their sentiments reflect "historical reality" is another question.